A long time ago, before civilization, before agriculture, before evil, before history, some young witches were having a sleepover. These were from a tribe of the earliest witches, and they wanted to find the most terrifying thing–to scare the bejeezus out of some wizards. As competition breeds innovation, they decided to have a contest. They gathered their materials, and brought them to a nearby cave. At the foot of it, they settled down; partly because they were too nervous to enter, but also because beautiful paintings from inside seemed to jump out in the starlight.

Thus, the contest began. “Bubble, bubble, soil and rubble,” one sang while stirring a potion, “Leaves swirl and cauldron bub—“

“Oh my goodness! What are you doing? It’s not going to be scary,” said another right by her ear.

“Shut up! I’m invoking the sublimate of the world. Doesn’t it scare you sometimes?” she replied.

“Yeah, but it’s more exhilarating,” countered the other, eyes narrowing. “You don’t even have a fire going.”

“I’m carbonating it!”

Everyone stared. All of a sudden, more arrived, dragging dead animals to the fore. Progress, they hoped.

“What is this?” said the frustrated witch, whose love for potions got her jittery.

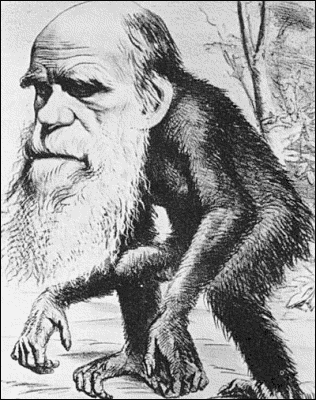

“We thought that we could jump into some animal skins and scare ‘em,” said the leader of the group that just came in. He looked puzzled as to why they weren’t excited. Saber-tooth tigers and bears are scary, right?

“I don’t want to get into bloody pulp and fur,” said the cynical witch who narrows her eyes.

“We’ll line ‘em, of course.”

“So we’re going dress as animals that they hunt… with wands?” said the first witch, growing more frustrated by the minute. The wizards had irked her – she had to get them back. Meanwhile, the cynical witch’s eyes widened – she started to like her.

“This is going nowhere!” cried the witch who threw the party.

“Not SO fast! I will conjure a spell of my own creation!” cried someone out of nowhere, holding her wand high—and majestically, chanting, “Witches of the blair, bring terror in the air.” She thrust the wand downwards, and BANG! Sparks flew, a fire roared, and soot blew into the sky!

It was kind of scary. But any fear gave way to enjoyment of the heat—it was getting chilly—or concern for the little girl—face painted with charcoal. The first witch saw the opportunity to bring her cauldron towards the fire. Bringing out cobalt goblets, she poured out some of her brew for everyone. “Tastes like tea,” said someone, surprised.

“The best kind of potion,” she replied. She was having a caffeine crash. Now, hands around her warm goblet, she could hear each bubble pop. It felt so serene.

“What the heck was that?” Everyone turned. It was the mother whose lair they were supposed to be sleeping at. She would have said “Hell,” but that did not exist then. Remember, this was a time before evil. There was no murder. No rape. No alcohol. Everyone looked to their cups, as if embarrassed. “You know that’s going to keep you up all night, right?” said the astute witch, recognizing the smell. “Ahh… gimme some. Now, what are you doing?”

They explained that they were trying to find the scariest thing, so they could spook the wizards. A glaze went over her eyes, as if clairvoyant, but they thought it was just the fire.

“I’ll tell you what’s scary. A story,” and without warning, she launched into one:

One day, a little girl was running by a lake. She had light brown skin, and dark black hair. When the grass underneath turned to a stone-beach, she jumped from rock to rock to the shore. She picked up a smooth flat rock, and threw it in the water; she laughed as it skipped twice. Then, she looked around, and saw a blonde man in the shade. His pale white skin seemed to penetrate the darkness he was in. She picked up another stone, and seeing that he was watching, turned back around and threw it as high she could, watching with glee as it came down. It burst through the surface, leaving behind ripples that spread far and wide, and the way it sank sparked her curiosity. Looking over her shoulder, smiling, she decided to pick a whole bunch of little stones and throw them in. The pebbles came down with a woosh, and little droplets splashed in the air. From the corner of her eye, she saw a turtle swim into view. It had a rock on its back, and it looked like a globe. What was a minute seemed like an hour, as time almost stopped. Each time the globe turned around unsteadily, she felt a rush. But the orb never fell off the turtle’s back, and the turtle never swam away. All of a sudden, the man appeared beside her, and skipped a rock towards the turtle. It hit the turtle’s shell and—startled—the turtle let the world fall. Laughing, the man looked at the girl who was crying. She felt like her own child was drowning. He picked her up—

A sob broke the mother’s concentration. Looking around, she saw a stunned audience…

“I think I get it,” said someone after awhile. “In the future, we’re judged based on our skin. That girl was light brown, and he was white. That rock represented her world—but also her home—that he took from her.”

Everyone looked at each other. Sure enough, they had different colour skin, but they had thought that made them distinct, not different. The fire illuminated their skin, but its warmth was gone. It was a strange fire, going without tinder.

“Not us,” said the mother confidently, “mere humans. We know that skin is only skin deep, what’s underneath is the same.”

“What about men and women?” another asked.

“They will not be equal. Men will have more power, but too much.”

“Sometimes wizards beat us at games. I never thought they’d hurt us,” said a witch, looking at her tea going flat.

“Not us,” said the mother, growing less sure.

“What about us?” a small voice said.

“We’re burned at the stake.” Glaze went over her eyes.

“Stop! Please make it stop!” cried her daughter.

But… it was too late. For once a story is told, it cannot be called back. Once told, it is loose in the world.

I told the story to my mom, who predictably interrupted to offer criticism. I told her to shut up, and pretend she was a child listening to a story. Once I got going, she was lost in the tale, laughing and falling into deep thought whenever I wanted her too. I felt so much power as a storyteller. Being able to change the dialogue to make it more visual the second go-around was nice. I found that I could start with ‘she said’ before rather than after, to make things more clear. Then, after I was done, she offered more criticism…

We talked about the transition from the story to the stunned audience. She said it was like she was the child–stopped from screaming–which I found really interesting. I cut off the story to leave it open to interpretation, because it could be that the girl was kidnapped, or thrown in the lake to drown, but it could also be that he picked her up to comfort her. The muffled scream was an element I didn’t even consider.

Lacking listeners, I told the story to my best friend over the phone. I could hear her breathing the whole time, too nervous to laugh ’cause she wanted me to keep going. After I finished, she said, “I have one question: If evil didn’t exist, how could fear?”

Works Cited:

Linder, Douglas. “A Brief History of Witchcraft Persecutions before Salem.” Famous Trials: Salem Witchcraft Trials. University of Missori-Kansas City, 2005. Web. 28 May 2015.

“Double, Double, Toil and Trouble: Annotations for the Witches’ Chants (4.1.1-47 [of Macbeth]).” Shakespeare-Online. Amanda Mabillard, 18 May 2014. Web. 28 May 2015.

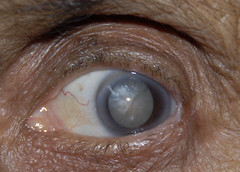

“Mature cataract.” Flickr. Bob Griffen, 2006. Web. 28 May 2015.

“The Ojibwe Creation Story of Turtle Island.” Native Drums. Department of Canadian Heritage, n.d. Web. 29 May 2015.