Although I had never heard of Jim Wong-Chu* before this class, I was immediately drawn to his collection once I learned of his work in preserving Chinatown, since I recently wrote an article in contribution to the current “Save Chinatown Heritage” movement.

This week, I studied a series consisting of correspondence sent to Jim Wong-Chu by friends (RBSC-ARC-1710-3), family, colleagues, and other writers, including Joy Kogawa (whose letter I couldn’t find), Rick Shiomi, Helen Koyama, Joy Kogawa, Andy Quan, Kam Sein, Paul Yee, Phil Hayashi, and Linda Uyehara Hoffman. <rbsc.ca>

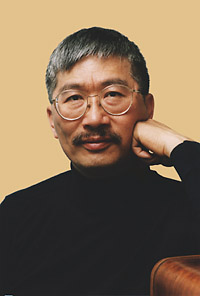

Jim Wong-Chu (via AsianCanadianWiki.org)

In particular, a letter from Helen Koyama** caught my eye (03-34). (First, because I thought I recognized the butterfly stationary.) The letter reads, in stark contrast to perfunctory addresses from editors and other colleagues, like a conversation with a close friend. In this message, Koyama briefs Wong-Chu about her life, almost as if writing in a diary: she is 3.5 months pregnant, struggling with writers block, and half proud, half envious of fellow writer Paul Yee’s success. “I’ll be 60 by the time I publish my first book!”, she complains good-naturedly.

Koyama’s letter offers us a rare glimpse into the life of a minority, female, children’s lit writer struggling to get published in the 1980’s. While the Japanese Canadian never mentions racial or gender tensions she does disclose that, as a busy homemaker, she hardly has time to sit down and write. In fact, it takes her a TWO WHOLE MONTHS to complete this letter. The letter, first dated October 19, 1983 at the top, is interrupted by new entries, which can be inferred by the change in typewriter ink or are mentioned by a self-conscious Koyama herself stating that “It is now Nov 4th.” Halfway through, Koyama gives up typewriting and switches to handwriting.

Koyama’s letter verbally articulated and physically demonstrated how her other roles as wife, mother often came into conflict with her identity as writer. But, it also led me to meditate on the difference between contemporary and older mediums of writing—and its implications for archival research.

Hand and typewritten letters allow you to be more aware of the process of creation. In the letter, Koyama explains that she has just received Jim’s latest letter, but even before she tells us, we know time has passed, because the ink is darker and the line spacing shifted. Today, digital technology makes it difficult to trace the passage of time and an author’s editing process during the creation of a work. While we can see Koyama trying to type around butterflies on the stationary and manually correcting “sentense” with a pencil, today, spelling mistakes are mitigated by Word autocorrect or quickly pressing backspace. These minute transformations are quickly forgotten. Digitalization creates a space for erasure; we lose that the ability to archive much of the creative process that happens while the author is writing—the crossed out phrases, replaced words, moved paragraphs, etc. Advancements in technology have occluded our awareness that creation is a temporal act, a performance. If Jimmy Wong-Chu had written on a lap top, then Box 2, with all the edited manuscripts and saved pages that couldn’t be sent to the publisher because of one typo, would not exist.

In “New Approaches to Canadian Literary Archives,” Hobbs emphasizes the need for archivists to understand the particular relationship writer share with their works, and to document the writer’s creative intention through their arrangement of the fonds. She writes, “What has lent the literary manuscript page its rarity and value in market terms is its proximity to the act of creation, its closeness to the spark or intention of the creative author” (113). As archivists in the 21st century, a large question will be how we can capture these increasingly transient and elusive moments of revision and rewriting that are integral to the ongoing process of creation.

Helen and son Robin at the Kaigai Manga Festival in Tokyo (via Drawn & Quarterly)

* Jim Wong-Chu is a “writer, photographer, historian, radio producer, community organizer and activist, editor, and literary and cultural engineer” (UBC Rare Books and Special Collection Archive). Born in 1949 in Hong Kong, he was sent to live with relatives in Canada as a “paper son“. Over the years, Wong-Chu has founded various community and cultural organizations including: Asian Canadian Writers’ Workshop, Vancouver Asian Heritage Month Asia Canadian Performing Arts Resource, and Ricepaper magazine. He was awarded the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal for his important contributions to shaping the Asian-Canadian voice.

** Helen Koyama is a Japanese Canadian children’s lit writer whose family was sent to live in internment camps during WWII. Today, she runs a publishing company in Toronto.

Hobbs, Catherine. “New Approaches to Canadian Literary Archives.” Journal of Canadian Studies 40.2 (2006): 109-19. Print.