This week, I had the pleasure of digging through the fonds of Kosaburo Shimizu (1892-1962). I’d like to start off with a brief biography of his life because I think it will be pertinent to the topic of my blog post. Shimizu was a Japanese émigré born in the village of Tsuchida in Japan. He came to BC in 1907 to live with his eldest sister after the death of his father. After graduating from Royal City High School, Shimizu taught English at the New Westminster Methodist Church. Against his family wishes, Shimizu decided to pursue his dreams for higher education and went on to study at the newly-established UBC in 1915 and obtained his MA in English Literature from Harvard. He was ordained into the United Church in 1924 and pastored several congregations in Vancouver. During the interwar period, Shimizu was an active participant in peacemaking efforts to resolve growing racial tensions between Japanese and White Canadians. During WWII, however, Shimizu was labeled as an “undesirable person” and deported to an internment camp in Kaslo, BC. After the war, he relocated to Toronto, where he lived with his family until his death in 1962.

In “Autonomous Archives,” Moore and Pell examine the autonomous archives of the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs, Hope in Shadows, and Friends of the Woodward’s Squat Archive as “oppositional spaces in which marginalised groups construct collective identities and discourses apart from dominating groups” (256). Intrinsic to the notion of marginalization is the idea of displacement. They write, “The intimate connections between these publics and their environments call attention to the significance of place for communities, and by extension for their archives. By connecting stories of past experiences to present localities, public histories give places meaning.” Autonomous archives, then, are places which document dis-placement.

One of the first things that caught my eye about Shimizu’s life was how well-traveled he was for a “foreigner” in the early 20th century. Yet many of his outings were not by choice. Displaced by the death of a parent, by war, and by discrimination, Shimizu never had a permanent “place” to call home or substantiate his history. It is sadly ironic but perhaps fitting that the 13 diaries that travelled with him to all these places found their final resting place in the institutional archive of a patriarchal society that never quite accepted him in the first place.

After reading about radical archives this week, it seemed mightily ironic that I would be attempting to draw conclusions about autonomous archives from works found in an institutional archive. In fact, it seemed quite the impossible feat. Yet, as I spent time with Shimizu’s fonds, it seemed to me that it was asserting its own autonomy and resistance against the archoviolific archive that housed it.

Today, I’d like to compare two of Shimizu’s journals. The first comes from his 1909 diary (RBSC-ARC-1500-01-01). It’s quite unruly (literally) and written mostly in Japanese, as be fits someone who had only recently begun learning English. Snippets of English such as “Ms Hill (presumably a school teacher)… arithmetic” or “Ms Hill… Tennyson” suggests that much of his discussions center on learning. Above all, Shimizu seemed to have a vested interest in geography—place names like Strathcona, measurements of the Fraser River—stand out from amidst the jumble of Hanzi characters. Shimizu’s diary seems to reflect a newly-immigrated 16-year old’s attempt to locate himself through linguistic and geographical markers, yet jumping back and forth between languages, he never does quite find a place of rest.

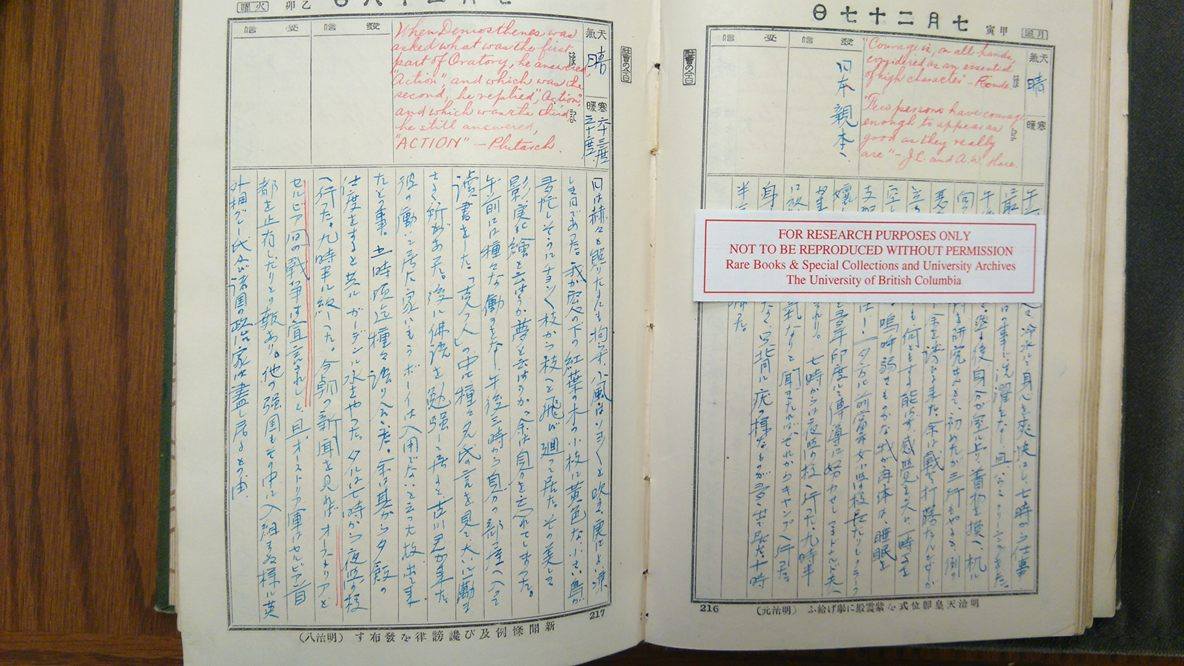

Shimizu’s later journals, like the one pictured above from 1916 (RBSC-ARC-1500-01-03), are much more organized and defined. What immediately strikes the eye is the segregation of Japanese and English on the page, highlighted by difference in ink colour. Each day is marked by choice words from the bedrock of the Western canon: Aristotle, Emerson, St. Paul, but Shimizu’s personal reflections, his moments of introspection, were hidden from me.

In “The Making of Memory,” Shwartz and Cook write that, “Like archives collectively, the individual document is not just a bearer of historical content, but also a reflection of the needs and desires of its creator…” (3). “Reading” Shimizu’s diaries, or rather, admiring the columns upon columns of beautiful Japanese script I could not decipher, I began to wonder whether or how these two passages related. Did the English quotations summarize his day? Encourage? Remind? Chastise? Or perhaps they were juxtaposed altogether arbitrarily. The archival descriptions did little to clear the enigma, as the curator obviously did not read Japanese either. Although indeed, UBC’s Rare Books and Special Collections has made Shimizu’s diary public, his decision to write in Japanese continued to assert his privacy and right to self-representation. The very fact that all these English words were boxed into a little square on his page seem reflective of someone compartmentalizing opposing cultural identities. Although, as a literature scholar, Shimizu undoubtedly held the Western canon in high respect, perhaps, we can go so far to say that the diary itself is resisting its inclusion in the institutional by counteractively placing hegemonic discourse in solitary confinement. Thus, while Shimizu’s fonds remain housed in a public archive, I believe that they function as an autonomous voice, one which too can “point to the intersecting concerns of social identity, claims to place, and the political stakes of representation within heterogenous and unequal publics” (Moore & Pell 255).

Note: Wondering how an autonomous archive for the Japanese-Canadian experience would look like? Last summer, my family visited the lovely town of Greenwood in interior BC and were surprised to learn at their local museum (run by two Japanese ladies) that many of their Japanese “interns” came from no other than our hometown, Richmond! Shimizu’s fonds were transferred to RBSC from Steveston United Church, which still stands as a historic site in Steveston Village.

Works Cited:

Moore, Shaunna and Susan Pell. “Autonomous archives.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 16.4 (2010): 255-268.

Schwartz, Joan and Terry Cook. “Archives, Records, and Power: the Making of Modern Memory.” Archival Science 2 (2002): 1-19.