Before the invention of the telegraph, communication over distances took a variety of forms. For example, bonfires signalled the arrival of ships, optical telegraphs transmitted messages from devices mounted on hilltops, and the military used semaphore signalling extensively throughout the Napoleonic wars. The problem with these devices, however, was their successful use depended on weather conditions and daylight, both of which were outside the control of the operator.

The invention of the battery by Alessandro Volta in 1800 made the electric telegraph possible. Francis Ronalds invented the first practical electric telegraph in 1816, but it would be another twenty-one years before the first commercial electric telegraph received its patent.

In 1837, the British team of Dr. William Fothergill Cooke and Professor Charles Wheatstone received a patent for their multi-wire, short distance communication telegraph that “worked effectively in notifying the passing of trains and in sending messages” (Kieve, 1973, p. 30). Also in 1837, American Samuel Finlay Breese Morse patented an electromagnetic telegraph that needed only one cable. This invention was less expensive and more reliable since it was capable of facilitating communication over longer distances than Cooke and Wheatstone’s telegraph.

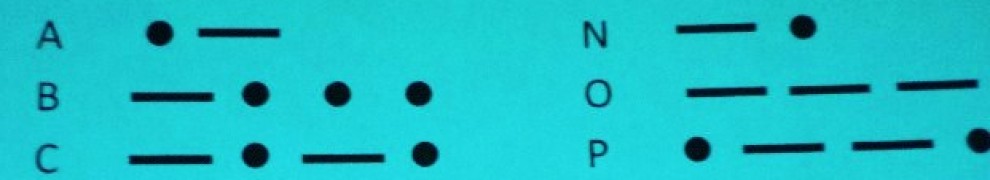

In the 1830s, Morse and his business partner, Alfred Vail, created a code consisting of dashes and dots to represent letters and numbers, known as Morse Code. Their telegraph sent electrical pulses down a wire that caused a hammer on the device to make an impression on a piece of paper. An operator familiar with Morse Code was required to decode the message contained within the dots and dashes. The early telegraphs used paper to capture the code until operators realized that they could decipher the code simply by listening to it.

In Morse Code, the most commonly used letters in the English language, such as “e”, had a simple code, with a more complicated code for infrequently used letters such as “z”,

. Morse Code worked well for translating English messages, but was not adequate for transmitting non-English messages because “it lacked letters with diacritical marks” (McGillem, 2012, para. 12). As a result, International Morse Code became the standard for message transmission outside of North America in 1851.

Although Morse received his patent in 1837, it would be another seven years before the first public message was transmitted. On May 24, 1844, Samuel Morse transmitted a message from Washington, D.C. to Baltimore, Maryland: “What hath God wrought!” (Lax, 2009, p. 10). After the successful transmission, Morse received support for the widespread use of his invention and telegraph lines started to expand. In fact, the ease of installing telegraph lines meant that many communities had telegraph communication before they had railway service. The telegraph connected Boston and New York in 1846, and Montreal and New York in 1847.

In 1852, Frederick Newton Gisborne achieved a significant Canadian milestone by successfully laying the first underwater telegraph cable in North America connecting New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. In 1861, the Western Union Telegraph Company succeeded in connecting the east and west coasts of the U.S. and in 1866, the first Atlantic cable linked Newfoundland and Valencia, Ireland.

Despite the expansion of the telegraph, the speed with which an operator could decipher Morse Code limited communication which led to message backlogs. In addition, there were not enough telegraph lines to permit efficient communication because “while a line was carrying one message, it couldn’t carry another” (Lax, 2009, p. 16).

The invention of the telephone by Alexander Graham Bell in 1876 addressed some of these shortcomings. For example, the telephone did not require a skilled operator to translate messages, and the quadraplex method resulted in “four messages traveling over the same wire at the same time” (Galloway & House, 2009, para. 7).

In the 20th century, the telegraph and Morse Code continued to co-exist with the telephone and its notable contributions included the receipt of the SOS message from the Titanic in April, 1912, and messages to announce the end of World War I and World War II. In the 1950s, the telegraph fell out of popularity with Canadian railways for communicating train orders. On December 31, 1999, the Global Maritime Distress and Safety System replaced Morse Code as the “international language of distress” (Fairley, 1997, para. 1).