Can Regional Dialects be considered as Oral Language?

While reading Chapter three in Walter Ong’s book Orality and Literacy, I reflected on the regional dialects that are prevalent in the Atlantic Provinces. Ong (1982) states that “It is not surprising, that oral peoples commonly and probably universally, consider words to have great power.” (p. 32) . Although our current way of life is dominated by chirographic (written) and typographic (print), in many regions if the world local dialects still exist.

The Atlantic Provinces are rich with local dialects. Many areas of Newfoundland have very specific ways of speaking; the Cape Breton Highlands are strongly influenced by their Gaelic heritage, our first nations populations have a regional presence, and the Acadian French population are prevalent in many small communities throughout the region. These areas all have specific dialects but the members of these regions communicate in the proper written forms of English or French. However, it is the richness of the oral language that helps to preserve their cultural identity.

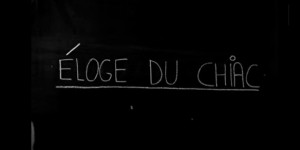

Acadian French language is a traditional (‘old”) form, spoken with a strong accent that differs from francophone areas of Canada. A specific local dialect that has evolved among the Acadians in south east New Brunswick is called “Chiac”. This dialect is of interest to scholars because it has evolved within the last century. It is a “language” that was developed by francophone youth, who live in the bilingual region of the province. Analysis of the language indicates that it is a combination of antiquated French (with a strong nautical reference), mi’kmaq, and English.

“The fact that Oral peoples commonly and in all likelihood universally consider words to have magical potency is clearly tied in, at least unconsciously, with their sense of the word as necessarily spoken, sounded and hence power driven” (Ong 1982, p. 32). Researchers feel that due to their minority status in the southeast region, and exposure to both languages, the young generation of Acadians developed a language that helped them to cope with diversity of the linguistic variance in their lives. It is also thought that Chiac had a rebellious undertone, as it was prohibited in schools, and alarmed older members of the Acadian community who were fearful of assimilation and loss of their culture. Presently, Chiac has a strong cultural (although at times controversial) identity within the community.

Ong (1982) states that “Of course, all expression and all thought is to a degree formulaic in the sense that every word and every concept conveyed in a word is a kind of formula, a fixed way of processing the data of experience, determining the way experience and reflection are intellectually organized, and acting as a mnemonic device of sorts.” (p. 35) Chiac is formulaic, as it has a very specific way of combining the words together. Those who speak Chiac use specific word combinations, and sentence patterns, with unwritten rules that must be followed.

Would Walter Ong consider this an oral language? Chiac is only represented in a written form through social media posts, poetry and song lyrics. As Ong states, the language is homeostatic and very much in the present (Ong 1982, p. 46). The words of Chiac meet the current demands of our society, but disappear from the speech of those who move away from the community. Perhaps this is stretching the definition, but I would like to believe that in the richness of local dialects, Ong’s orality still exists.

Brault, M, (1969) Éloge du Chiac retreived from : https://www.nfb.ca/film/eloge_du_chiac

Cyr, J. (2014)Le Chiac ou L’Insoutenable légèreté du parler Acadien retreived from : http://astheure.com/2014/01/20/le-chiac-ou-linsoutenable-legerete-du-parler-acadien-jasmin-cyr/

Deschamps, M. J. (2012) Chiac: A pride or threat to French? Official Languages Commission, retrieved from: http://www.officiallanguages.gc.ca/en/cyberbulletin_newsletter/2012/october-11

Ong, W. (1982) Orality and Literacy, Methuen and Co Ltd. London England.

What an interesting perspective! I can certainly appreciate this view being from one of the Atlantic provinces! It is so true that the dialects present in our provinces are not seen as proper written form and it is easy to see how written language could be quite difficult for students who are so entrenched in their dialect. One example that I see in my classroom fairly often is the following sentence:

I seen the dog running down the road.

The use of the word ‘seen’ instead of ‘saw’ is very much a dialect thing for many parts of my province. These students hear their parents say this all the time so it is obviously what they write. It is very difficult for me to convince them that the correct form is the word saw.

I’ve got a picture that is a great example too! It has been going around on Facebook a lot over the past few days. 🙂 I’m going to try to post it here!

I cannot figure out how to add the picture in a reply. I can get it to work on an original post, but not a reply! 🙁

Your post reminded me of all the varying dialects in China – all of which sound very different from each other. It is almost like they are an entirely different oral language. For example, main land Mandarin has 4 tones to the language whereas Cantonese has 9 tones. However, the only thing they have in common is the written text. This consistency in literacy makes it more functional for the country. An individual can migrate between regions and still understand the text even if they cannot communicate orally. It makes me wonder how the future generations learn these dialects. If there is no written text used to distinguish between these dialects then similar to Chiac, would it make these oral languages as well?

Great post! Both of my parents are from Trinidad, so growing up I was exposed to their patois and often use it when I speak English. When I was young and my friends came over to my house, they used to comment that it sounded like my parents (especially my father) was speaking a different language, because their accents were laced with so many terms that are foreign to anyone not from the Caribbean.

When I was young I always said “tree” instead of “three” and “axe” instead of “ask”. I was quickly corrected in elementary school. Jennbb commented earlier that it is hard for her to convince students that what they were saying when using certain phrases that stem from their dialect was not correct, I often felt the same way and when I tried to “correct” my parents I would be scolded and told,”I was too educated”. Funny. I definitely think that dialects are part of oral languages because like the author of this post said it preserves the culture that it steams from.

Hello Lynn,

Thank you for posting about dialects and Chiac. It’s commonly perceived that Canada is mainly synced to a North American Standard dialect. Perhaps for a large geography, having fewer variances than other countries is remarkable, but you highlight the variety that is really on the ground. I have heard about the ‘doughnut’ effect in Montreal – Anglophone dialects within a Francophone milieu, inside a larger Anglophone context – but I am not as familiar with the East Coast, which of course has had plenty of influences.

Ong (1982) writes “an oral culture has no texts.” Perhaps historically Chiac had none and lyrics and poetry were only recently captured, but as you indicate that Chiac has a place in social media. I would posit that those new digital texts are signs of a growing language with a relevant place in the world. Languages can be revived: Hebrew is a great example. I don’t know if Ong would confer ‘oral language’ status on Chiac (or many other dialects for that matter). I sense a disdain in his binarism. He doesn’t even like the term ‘oral literature’ and would rather see it eliminated, with all that it could offer on the continuum traditions (as he notes, it is ‘fortunately’ losing ground). There doesn’t seem to be room for other possibilities outside the oral-literate paradigm. As Biakolo (1999) notes, ‘We are often left with the impression that these scholars are working backwards to answers assumed from the start.’ Ong might actually fall on the ruling elite side of the fence, banning Chiac in schools.

In the former Soviet Union, occupied countries’ languages were also banned. I didn’t grow up there, but I did grow up speaking and studying Lithuanian at church and at school once a week in Toronto, all mandated by the diaspora community as a way to keep the culture alive, lest the country never return to independence. Despite the control and bans over the texts of a small nation by another, in fact it is orality that maintained the language and culture (e.g., people attending church services secretly if not publishing on the sly). As much as I appreciate our literate societies, I see orality as a strong survival tactic. I’m not going to go so far as to say that there was anything magical or mystical about it, but words spoken and sung near and far, remembered by oral tradition, do have power if their survival is any testament. Only as oral cultures wane (or are forced to change) does literacy take their place. I often find myself hoping that the folk songs I grew up with are documented somewhere, even if I never sing another word.

As the edict goes, “a language is a dialect with an army and a navy.” I often think about this when I inquire what any country’s ruling dialect is (whether it be “high” German, or the most beautiful dialect that was selected as Italian, or Standard Modern Arabic, etc.). Which brings me to wonder, what exactly then is the Canadian ‘language’ and how did one dialect win over the others?

Julia

Sources:

Ong, Walter. (1982.) Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen.

Biakolo, E. A. (1999). On the theoretical foundations of orality and literacy. Research in African Literatures, 30(2), 42-65.

Oh I wish I had got to this posting sooner. Fascinating discussion

Terry