In his work, Walter J. Ong (1982) provides us with a definition of primary oral cultures – within these cultures there is no knowledge of, or even the possibility of, writing. His description of these primary oral cultures, and further the comparisons he draws between these and fully literate cultures, invited me think about our culture from a new perspective.

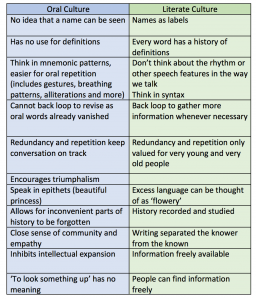

Ong’s (1982) comparisons of cultures encourages the reader to think of how big an impact writing has had on society. I agree with Ong’s argument that I, coming from a literate culture, can never fully comprehend how an oral culture thinks, communicates and learns. Throughout Ong’s writing, however, I was able to think more critically about the vast differences between the two cultures and their thought processes. I put together a concise table to help keep track of my thoughts while reading.

Interestingly, Ong (1982) argues that oral narrative poets were better authors than their literate counterparts; learning to read and write are very controlling and interfere with the oral composing process. In my grade 6 class, the process of analyzing and writing poetry can sometimes be a struggle. I wonder how I can get my students to feel free of literary constraints to author poems? It’s something to think about.

Ong (1982) argues that, oral societies have to repeat over and over again the learnings from the past. “This need established a highly traditionalist or conservative set of mind that with good reason inhibits intellectual experimentation” (Ong, 1982, p. 41). In a primary oral society, there is limited access to information. John Willinsky (2002) discusses vast spread of information with the rapid development of the internet. He argues that open access to educational information would benefit society. I can’t help but think back to the traditionalist and conservative primary oral cultures and think just how much has changed. Ong has really opened my eyes to literacy being a technology that has shaped our current world. Is it, as Ong (1982) argues, the most important technological innovation of humankind?

From Ong’s (1982) description of primary oral sources, to Willinsky’s (2002) arguments for a more accessible public space for knowledge – written text and openly available information has certainly transformed societies. James O’Donnell’s (Engell & O’Donnell, 1999) argument of technological innovation shaping civilization certainly, I believe, remains true today. O’Donnell discusses technology bringing both loses and gains. In elementary education, this is an aspect I try to get across to other staff when encouraging them to try something new, as well as with my students when discussing technology in the modern age – technology doesn’t bring a one size fits all mentality – there will always be loses and there will always be gains.

References

Engell, J. (Presenter) & O’Donnell, J. (Presenter). (1999). From Papyrus to Cyberspace [radio broadcast]. Retrieved from https://canvas.ubc.ca/courses/4290/files/609973/preview

Ong, W. J. (1982). Orality & literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd.

Willinsky, J. (2002). Democracy and education: The missing link may be ours. Harvard Educational Review, 72(3), 1-21. Retrieved from: http://knowledgepublic.pbworks.com/f/WillinskyHER.pdf

kristie dewald

May 31, 2018 — 5:27 pm

Thank you for this post and the table! Like you, I believe Ong’s assessment that those of us from a literate culture can never really understand an oral culture. I have found this topic enthralling, frankly. Often while reading Chapter 3, my mind would try to relate a concept to what I know but then I would recognize that I was invoking images that stem from writing or some visual representation of language. It is difficult to think that there ever was or that there are today – in 2018 – cultures that have no form of writing while we are living with this technology that has become so integrated in our lives and thought processes that we literally cannot imagine a world without it. Is that what users of information technology will think in…400 years? 40 years? 4 years? I am confident there are young people today that could not imagine a world without the Internet or WIFI, but they still have us to remind them of that time. (“when I was your age….”)

It is an interesting question you pose as to whether writing is perhaps the most important innovation of humankind. If not the most important it would certainly rank high up the list, I would suggest. Now the tool of the internet presents us with an opportunity to more widely disseminate all that writing in a way that makes the printing press near obsolete. I tend to agree with Willinsky’s suggestion that knowledge and research be freely and widely distributed. He raises a couple of valid concerns such as that contrary and critical critiques require some management, but presents reasonable solutions to the problems. Beyond those presented in the article, it is difficult to think of an argument against open access that is not purely protectionist, tied to ego, insecurity and entrenched establishment type of thinking (I am thinking here about institutions such as Universities that reward faculty not just for publishing, but publishing in a particular subset of journals).

It will be interesting to see where things go in the next decade or so.

References:

Ong, W. J. (1982). Orality & literacy: The technologizing of the word. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd.

Willinsky, J. (2002). Democracy and education: The missing link may be ours. Harvard Educational Review, 72(3), 267 – 392

Kathryn Williams

June 5, 2018 — 11:40 am

Hi Kristie,

Thanks for your response. I too find myself enthralled in this topic – which was slightly unexpected and a pleasant surprise! With regards to access to research, I appreciated your comment about protectionism and ego. How do you think the authors of academic work feel about this stance? It is interesting to think about it from an alternative perspective.

Kathryn

Marcia

May 31, 2018 — 9:21 pm

I thoroughly enjoyed reading your post and I really liked and appreciated the table you created.

After reading your post, I was able to really reflect on the idea of literacy as technology. I, too, sometimes wonder which direction technology is really leading us.

There were a few things from your table really stood out to me strongly. Most likely because my teaching experience is mostly with young children, I thought about how you noted that repetition is most helpful for the very young or very old. This is very true and I wonder if it is the same way in an all oral culture. Children probably enjoy hearing the same stories told over and over again, and I know that they definitely enjoy hearing the same songs sung over and over again so perhaps that might be a similarity in both cultures, at least for young children.

Another interesting note from your table was the idea that parts of history could be forgotten. I’m sure there are millions of people in the world who wish they could forget many awful moments in history. I can’t imagine being able to do that, to simply not pass stories on to the next generations or to keep information locked away from the rest of the world.

Finally, the idea that literate cultures lack the community and empathy of oral cultures really stood out to me. Is technology making us more robotic and machine-like? Are we trying to be so self-sufficient and self-diagnosing that we are driving away the rest of the world and isolating ourselves? It is a very interesting and frightening thought.

You mentioned staff resistance to trying new things. How do you deal with this? I’m always interested to hear how this is dealt with among staff.

Thank you for your post. Really enjoyed reading it.

Marcia

Kathryn Williams

June 5, 2018 — 11:44 am

Hi Marcia,

Staff resistance to try new things is something that I am working towards being more empathetic (and less robot like!) about. I used to assume that people were excited to try new strategies and tools in their classroom but soon found that this was not always the case. I find that the strategy that works best for me is to team teach; this way the reluctant teacher can see a new technology working and the student engagement whilst working together. I’d love to hear some other successful strategies!

Thanks

Kathryn

david nelson

June 1, 2018 — 9:43 pm

I too really enjoyed reading your post and the table that you made. Experiencing a traditional oral culture within my school has opened up my eyes to many of ideas within your table but I am going to focus on the section where inconvenient parts of history can be forgotten, and not being able to back loop.

I would like to first expand on the fact that inconvenient parts of oral history can be forgotten/neglected. (At least for a while.)

“‘The essence of the treaty was to create a nation together that will exist in perpetuity, for as long as the sun shines, the grass grows and the waters flow,’ Anderson said. ‘The core concept is to share the traditional land of the First Nations who have entered into a treaty with the Crown and the Canadian settlers, and also to benefit from the Crown’s resources, such as medicine and education.’

But the text of the written treaties tells a whole other story. According to these documents, native groups surrendered all of their rights to the land in exchange for small reserves and meagre compensation.

For the British Crown, the treaties offered substantial benefits, such as:

freeing up land for loyalists who had supported the British during the American War of Independence;

advancing colonization in the West;

providing agricultural land and natural and mineral resources” (Montpetit, 2011).

Elders and the British Crown worked on substantially different terms when it came to orality and literacy. Much of what the indigenous people agreed on was through oral interpretation where-as the British crown used documentation. The problem with this was the fact that documents were forever and able to be back looped whereas oral culture was in one sense muted by the British Crown. This created a different interpretation of treaties and essentially got us into the mess we are in now. An original inconvenient agreement for the British crown was able to be forgotten…for a while. It was not until later that the oral agreements were recognized and treaties were reinterpreted.

Montpetit, I. (2011). Treaties from 1760 – 1923: Two sides to the story | CBC News. [online] CBC. Available at: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/treaties-from-1760-1923-two-sides-to-the-story-1.1081839 [Accessed 2 Jun. 2018].

Kathryn Williams

June 5, 2018 — 11:52 am

Hi David,

As a keen historian, I really appreciated your insightful post. The conflict between oral treaties versus the version written by the British Crown has certainly caused immeasurable long term damage. Your example really makes this topic hit home.

I’m currently living in the UK and I teach History to grade 5 and 6 at my school. Throughout these two years we look at Britain in many time periods such as the Tudors, the Victorians and WWI. One aspect that I really love to delve into is source analysis. For example, some people were literate in the Tudor time, others were not. I might ask the students, why would various accounts of an event be so different, or, whose perspective are we reading this account from? I find that these types of questions really gets the kids thinking!