The controversy over the best evaluation design continues to rage. During the late 1970s and early 80s, many debates were held at professional evaluation meetings about the value of experimental design in evaluation. Many evaluators thought the issue had been laid to rest, i.e., there was an acknowledgement of the usefulness and appropriateness of experimental designs–sometimes, but a consensus that such an approach does not constitute a gold standard, and not even the most frequently used design.

For many evaluators, especially in education but also in other fields, this prior understanding has been turned on its head by the US Government endorsement of randomized clinical trials as the sine qua non approach in evaluation (followed by quasi experimental and regression discontinuity designs). There has been considerable reaction to this methodological/ideological turn, with strong objections by AERA, AEA, and NEA.

AEA’s position, which follows, created much controversy within the organization–and even resulted in a “Not AEA Statement” on the use of RCTs. The issue was debated by Michael Scriven and Mark Lipsey at a conference at Claremont Graduate School, and this debate is summarized in Determining Causality in Program Evaluation and Applied Research: Should Experimental Evidence be the Gold Standard? which also includes the text of the “Not” statement.

Another useful presentation about the issue of RCTs is a one given by Michael Q Patton to NIH in September 2004. This talk The Debate about Randomized Controls as the Gold Standard in Evaluation focuses especially on the confusion of design and purpose.

You can read more about the issue in a previous post of the invited APA address I gave in August on educational evaluation as a public good.___________________________________________________________________

American Evaluation Association Response

To

U. S. Department of Education

Notice of proposed priority, Federal Register RIN 1890-ZA00, November 4, 2003

“Scientifically Based Evaluation Methods”

The American Evaluation Association applauds the effort to promote high quality in the U.S. Secretary of Education’s proposed priority for evaluating educational programs using scientifically based methods. We, too, have worked to encourage competent practice through our Guiding Principles for Evaluators (1994), Standards for Program Evaluation (1994), professional training, and annual conferences. However, we believe the proposed priority manifests fundamental misunderstandings about (1) the types of studies capable of determining causality, (2) the methods capable of achieving scientific rigor, and (3) the types of studies that support policy and program decisions. We would like to help avoid the political, ethical, and financial disaster that could well attend implementation of the proposed priority.

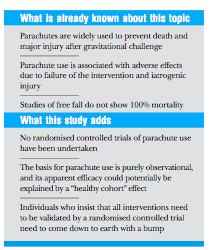

(1) Studies capable of determining causality. Randomized control group trials (RCTs) are not the only studies capable of generating understandings of causality. In medicine, causality has been conclusively shown in some instances without RCTs, for example, in linking smoking to lung cancer and infested rats to bubonic plague. The secretary’s proposal would elevate experimental over quasi-experimental, observational, single-subject, and other designs which are sometimes more feasible and equally valid.

RCTs are not always best for determining causality and can be misleading. RCTs examine a limited number of isolated factors that are neither limited nor isolated in natural settings. The complex nature of causality and the multitude of actual influences on outcomes render RCTs less capable of discovering causality than designs sensitive to local culture and conditions and open to unanticipated causal factors.

RCTs should sometimes be ruled out for reasons of ethics. For example, assigning experimental subjects to educationally inferior or medically unproven treatments, or denying control group subjects access to important instructional opportunities or critical medical intervention, is not ethically acceptable even when RCT results might be enlightening. Such studies would not be approved by Institutional Review Boards overseeing the protection of human subjects in accordance with federal statute.

In some cases, data sources are insufficient for RCTs. Pilot, experimental, and exploratory education, health, and social programs are often small enough in scale to preclude use of RCTs as an evaluation methodology, however important it may be to examine causality prior to wider implementation.

(2) Methods capable of demonstrating scientific rigor. For at least a decade, evaluators publicly debated whether newer inquiry methods were sufficiently rigorous. This issue was settled long ago. Actual practice and many published examples demonstrate that alternative and mixed methods are rigorous and scientific. To discourage a repertoire of methods would force evaluators backward. We strongly disagree that the methodological “benefits of the proposed priority justify the costs.”

(3) Studies capable of supporting appropriate policy and program decisions. We also strongly disagree that “this regulatory action does not unduly interfere with State, local, and tribal governments in the exercise of their governmental functions.” As provision and support of programs are governmental functions so, too, is determining program effectiveness. Sound policy decisions benefit from data illustrating not only causality but also conditionality. Fettering evaluators with unnecessary and unreasonable constraints would deny information needed by policy-makers.

While we agree with the intent of ensuring that federally sponsored programs be “evaluated using scientifically based research . . . to determine the effectiveness of a project intervention,” we do not agree that “evaluation methods using an experimental design are best for determining project effectiveness.” We believe that the constraints in the proposed priority would deny use of other needed, proven, and scientifically credible evaluation methods, resulting in fruitless expenditures on some large contracts while leaving other public programs unevaluated entirely.

Follow

Follow

Most Significant Change (MSC) is a participatory monitoring technique based on stories of important or significant changes – they give a rich picture of the impact of an intervention. MSC can be better understood through a metaphor – of a newspaper, which picks out the most interesting or significant story from the wide range of events and background details that it could draw on. This technique was developed by Rick Davies and is described in a

Most Significant Change (MSC) is a participatory monitoring technique based on stories of important or significant changes – they give a rich picture of the impact of an intervention. MSC can be better understood through a metaphor – of a newspaper, which picks out the most interesting or significant story from the wide range of events and background details that it could draw on. This technique was developed by Rick Davies and is described in a