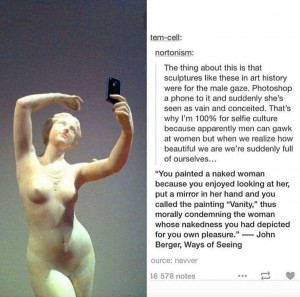

This is a bit late but here’s a cool little internet post that shows Berger’s observations in action.

Power, Power Relations, and Relationships

Out of all the philosophers we’ve read so far, I think I find Foucault the one most relatable to my own thought processes (This has nothing to do with my presentation I just had to start with something). I especially liked his more in depth look into the concept of power. Foucault, to my understanding, challenges the idea that power as a concept is an externally granted “object” that you either have or you don’t. Instead, he sees power as a relationship between two parties in which one party shows dominance and the other shows submission. Meaning that, although one person may be acting as an authority, it is the other party’s choice to then either act like a subject, an equal, or a higher authority. So that an authoritarian being’s power lies in their subjects’ active submission. We’ve seen several examples of this, like in The Tempest in that Prospero’s power lies in his control over the people on the island, or that the kingsmen lose their status on the boat once the helmsmen no longer thinks them worthy of his worship; or in The Bloody Chamber (short story), that the protagonist chooses to marry and live “under” the Marquis; or even in many of the Dabydeen poems, in which the slaves reclaim their power by rebelling against their masters in spirit by singing about defiling white women and such.

If my understanding is correct, then a power-powerless relationship, when understood in this context, would be very malleable and it would consistently see a shift in power to the point where all parties are eventually equal because of their ability to cease and deny power. In this way, a relationship of power is more like a relationship of compromise and coordination (or not because I tend to have a pretty “we’re all in this together” view of the world).

I’m trying to lead to the question I have, which I hope will make sense now:

If power (as an external object that is passed down a hierarchy) does not exist, but only the dominance and submission of interacting parties, is it possible to re-frame the entire hierarchical structure of our modern and majorly capitalist society so that the need or concept of “power” is eliminated? In other words, if we never saw power as a hierarchy, but initially defined it the way Foucault has, would our society look more like Rousseau’s nascent society? Or something more socialist/communist? If we start trying to shift out paradigm now, is there a middle ground that we could effectively reach?

I Can’t Handle The Truth

A discussion we had in seminar that really stuck with me was the one about truth. We went off on a tangent trying to determine whether or not the truth is objective or subjective. This really stuck with me. I thought about it for a while and each time I’d come up with a theory, I’d compare it with something we’d already read to see if I had reached any particularly new conclusions. This is the conclusion that makes the most sense to me right now, without fully allying with a concept we’ve already studied:

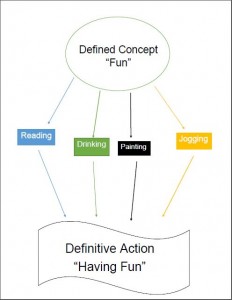

I think that the truth is both subjective and objective. It’s confusing to think about, but the objectivity and subjectivity of any concept  within our capabilities to discuss seems to always fall into a causality dilemma (like the chicken and the egg). So for you understand why I think this, I have to explain why I think the truth (or any concept) is objective and subjective at the same time. We start with a concept that is understood enough to gestate and further define, like the concept of fun. When fun is defined as something that is entertaining or pleasurable, this defined concept of fun is objective. However, because different people perceive the world differently, when the concept of fun is internalized, it comes to mean different things. For some it means reading, other drinking, others jogging etc. Even though all of these actions are definitively different, they are also still considered fun. So that, if, in the same room, a person was reading and another was dancing and a third was drinking, everyone in that room would be having fun. When everyone in The Fun Room is having fun, the definition of fun is relative to each person but also objectively defined as doing what it is they find entertaining or enjoyable. On a wider scale, if we look at initial objective definition of fun (the defined concept), we have to acknowledge that at one point this objective definition was a subjective one. Someone once decided that pleasurable or enjoyable things should be called “fun” and so they were when everyone adopted the objective definition and applied it subjectively.

within our capabilities to discuss seems to always fall into a causality dilemma (like the chicken and the egg). So for you understand why I think this, I have to explain why I think the truth (or any concept) is objective and subjective at the same time. We start with a concept that is understood enough to gestate and further define, like the concept of fun. When fun is defined as something that is entertaining or pleasurable, this defined concept of fun is objective. However, because different people perceive the world differently, when the concept of fun is internalized, it comes to mean different things. For some it means reading, other drinking, others jogging etc. Even though all of these actions are definitively different, they are also still considered fun. So that, if, in the same room, a person was reading and another was dancing and a third was drinking, everyone in that room would be having fun. When everyone in The Fun Room is having fun, the definition of fun is relative to each person but also objectively defined as doing what it is they find entertaining or enjoyable. On a wider scale, if we look at initial objective definition of fun (the defined concept), we have to acknowledge that at one point this objective definition was a subjective one. Someone once decided that pleasurable or enjoyable things should be called “fun” and so they were when everyone adopted the objective definition and applied it subjectively.

This is hard to look at in terms of the truth because “truth” is a much broader concept. But I like to think about the truth in this way so that I don’t have to stay up all night (lol). But if everyone in the same room feels like they know the truth, then everyone in that room subjectively knows their internalized form of an objective definition of the truth. I can see how this seems the same as Plato’s idea of the Forms, but I don’t think it is. Believing in the forms implies that all things have a “correct” objectively defined concept. I don’t think this is true because I believe that any objective definition was at one point subjective and then made objective by popular consensus of it.

I’m not a philosopher (at all), so this probably has a lot of inconsistencies and details overlooked. Feel free to distort my conception of the world, though. Totally will not put me into crisis mode.

The Gustl In Me

I don’t think Lieutenant Gustl is a very swell guy. I think he’s proud, melodramatic, and a lot of talk. He spends most of the story contemplating his life, and even his own suicide. in a rather materialistic way. He thinks about how the papers would report it, how his friends would react, how awful the whole situation he’s in is, and, most of all, who he could blame for his unpleasant night and the consequent suicide. However, I could not help but enjoy peeking into his brain.

Lieutenant Gustl is the first piece of published literature to be completely written through a stream of consciousness. This basically means that Schnitzler sat down, set pen to paper, and didn’t stop writing until the story was over. The fact that I read Gustl’s absolutely absurd thoughts in a manner very similar to the way I feel my own thoughts, made it relatable in a way I almost wasn’t aware of. Gustl is not the first main character I didn’t like. I remember reading five books between starting and finishing The Catcher in the Rye just because I didn’t like it very much inside of Holden Caulfield’s mind. But it was very different with Gustl because, as I read the text, even as two completely different people, it was so innately clear that we were both human. It was almost as if I couldn’t separate my own sporadic train of thought from Gustl’s while reading this piece. And so, to make this excessively broad, how different would the world be if we could all understand each other this intimately?

I see that when I saw his rather superficial view of the world, I realized I didn’t like him very much. However, Gustl is most definitely not the only superficial person to exist. If I were to be reminded of the incredibly significant trait of humanity that I share with a person and therefore relate to every superficial person on the same level I related to Gustl, how much easier would it be for me to go about my life? How much harder would it be to hate someone if you always knew how much you had in common? That our differences (religion, opinions, race, gender) are just various manifestations of our similarities? Also, how does it all relate to Rousseau’s thoughts on the nascent man and Plato’s thoughts on the structures of society?

Nightmares and Warm Milk

Last week we covered a couple of children stories (Snow White and The Sandman) and one thing they definitely had in common is that they were both pretty creepy. Because I can’t really wrap my head around the moral purpose of Snow White, my question revolves more around The Sandman. Are children so hard to get to bed that they need to be threatened with a stranger barging into their room, stealing their eyes, and rendering them blind for the rest of their lives to do it?

In the folktale of The Sandman (not to be confused with the text we read), a child loses his eyes because he didn’t go to bed at the time his mother told him to. In The Little Red Riding Hood, for example, Red loses her grandmother and gets eaten because she talked to a stranger. I’m pretty sure we’ve all been told that if we held a funny face for too long, it would stick. Before I wrote this, I tried to think of a famous fable with a reasonable moral that didn’t use a fearful (and sometimes grotesque) threat against a child’s wellbeing to convey its moral across to its audience. I could only think of one, even in choosing to analyze the more modern version adapted for our own generation’s consumption. Why must we scare kids into doing what we know is best for them?

From experience, I know that children don’t always know what is best for them and after what feels like (or literally could be) hours, a caretaker usually just wants something easy for them to do and hard for the kids to ignore. A story is very easy to tell, and fear, at any age, is very difficult to ignore. Scary stories don’t need to be logical (wolves can totally pass off as grandmas), but they can still be just as effective. But how effective is it really? If we take the moral of Little Red Riding Hood we learn that we shouldn’t talk to strangers. But the older you get, the more surrounded by strangers you become. We see strangers as a step before acquaintances or even friends rather than wolves intent on harming us and our families. And if someone maintains the view that everyone is a wolf, they generally find it more difficult to adapt to the dominantly extroverted culture of today.

What I’m trying to say is that we grow up to learn that these stories were made to scare us into the actions they encouraged. Once we realize this, we end up talking to strangers, going to bed pretty late, and making funny faces all day long.

This got a lot longer (and a lot less organized) than I intended it to be, but I just wanted to also mention that not abusing children’s immaturity goes a very long way. The one fable I could think of that wasn’t scary, the tortoise and the hare, is still one that is relevant to my life today (Pace yourself. Be humble. Believe in your abilities. Focus on your own goals rather how close other people may be to reaching the same goals.). Sure, it takes a bit more effort to think of a story for children that meets the criteria of being interesting to children, morally relevant (even in the face of changing generations), and effectively serves its purpose. But in an ideal world, I’d much rather put my child to bed with a warm cup of milk than a nightmare.

Last week we covered a couple of children stories (Snow White and The Sandman) and one thing they definitely had in common is that they were both pretty creepy. Because I can’t really wrap my head around the moral purpose of Snow White, my question revolves more around The Sandman. Are children so hard to get to bed that they need to be threatened with a stranger barging into their room, stealing their eyes, and rendering them blind for the rest of their lives to do it?

In the folktale of The Sandman (not to be confused with the text we read), a child loses his eyes because he didn’t go to bed at the time his mother told him to. In The Little Red Riding Hood, for example, Red loses her grandmother and gets eaten because she talked to a stranger. I’m pretty sure we’ve all been told that if we held a funny face for too long, it would stick. Before I wrote this, I tried to think of a famous fable with a reasonable moral that didn’t use a fearful (and sometimes grotesque) threat against a child’s wellbeing to convey its moral across to its audience. I could only think of one, even in choosing to analyze the more modern version adapted for our own generation’s consumption. Why must we scare kids into doing what we know is best for them?

From experience, I know that children don’t always know what is best for them and after what feels like (or literally could be) hours, a caretaker usually just wants something easy for them to do and hard for the kids to ignore. A story is very easy to tell, and fear, at any age, is very difficult to ignore. Scary stories don’t need to be logical (wolves can totally pass off as grandmas), but they can still be just as effective. But how effective is it really? If we take the moral of Little Red Riding Hood we learn that we shouldn’t talk to strangers. But the older you get, the more surrounded by strangers you become. We see strangers as a step before acquaintances or even friends rather than wolves intent on harming us and our families. And if someone maintains the view that everyone is a wolf, they generally find it more difficult to adapt to the dominantly extroverted culture of today.

What I’m trying to say is that we grow up to learn that these stories were made to scare us into the actions they encouraged. Once we realize this, we end up talking to strangers, going to bed pretty late, and making funny faces all day long.

This got a lot longer (and a lot less organized) than I intended it to be, but I just wanted to also mention that not abusing children’s immaturity goes a very long way. The one fable I could think of that wasn’t scary, the tortoise and the hare, is still one that is relevant to my life today (Pace yourself. Be humble. Believe in your abilities. Focus on your own goals rather how close other people may be to reaching the same goals.). Sure, it takes a bit more effort to think of a story for children that meets the criteria of being interesting to children, morally relevant (even in the face of changing generations), and effectively serves its purpose. But in an ideal world, I’d much rather put my child to bed with a warm cup of milk than a nightmare.

Some Overdue Confusion

I’ve written this up a few times and it only seems to get more and more confusing so I’m ditching formality. I can’t seem to wrap my head around Plato’s idea of morality or perception (which are so heavily reliant on each other). Okay, so to start off, we need to consider Thrasymachus, the only person to persistently argue against Socrates in that morality is relative. Book II is dedicated to prove Thrasymachus wrong but Socrates only really disproves Thrasymachus’ literal statement that “justice is nothing other than what is advantageous for the stronger” (338c) by arguing that a just man lives well and therefore advantageously but whether or not a just man lives advantageously is not what determines whether or not justice has one absolute definition. Yet, the book goes on and we nearly never hear of the possibility of individually relative perception/definition of justice/morality but we do hear a whole lot of agreeing to Socrates’ opinions on how we all ought to live.

Later on, in Book 7 we’re introduced to the allegory of The Cave. To explain the entire education and perception of man, Plato puts all of mankind in a cave where they are only able to look at one wall where shadows of imitations of what is outside the cave are projected. This means that everyone is receiving the same information but no one is able to see anyone else’s perception or what is actually even there. Then, Plato takes philosophers out of The Cave where they see how the world really is and then they are forced back in to live the rest of their lives in the grave dimness that is the world of the “cave-people”. But how do we know that those who left saw the same thing if neither of them could ever explain it? How do we know that the Forms have absolute structures if their structures could very well be completely different to those who have seen them but equally indescribable? Can we really trust Plato as the only person who knows what is true if he needs to lie (a lot of lies that are to his political and social gain) to get the rest of us barely close enough to see the “real truth”?

P.S – This was supposed to be posted last week but I have had a lot of computer trouble. Sorry.

Hey there,

My name is Farah El-Afifi. I’m originally from Cairo (Egypt), but I’ve moved a few times between there and Vancouver since I was four. I like to write quite a bit but I don’t really know what to tell everyone so we’re both in for a surprise. I joined Arts One for pretty much the same reasons everyone else did: I like to read, I like to write, I like to talk, and I like to be challenged.

My favourite colour is blue. I’m very passionate about making and listening to music. I sing. I play the guitar and the ukulele. I like art (and would be very down for a visit to the Vancouver Art Gallery anytime). I collect notebooks. I’m a list-maker. I like people and love getting to know them. I’d prefer it if you asked before you touched my hair (lol). I’d really like to major in International Relations and Journalism because I like to travel and intercultural exchange/awareness/studies are kind of my jam. I have a five-foot teddybear named Humphrey. I get self-conscious when I talk about myself for too long so this is, unfortunately, the end of the post. Let’s have a conversation sometime.

Thanks for reading,

Farah