Last week we covered a couple of children stories (Snow White and The Sandman) and one thing they definitely had in common is that they were both pretty creepy. Because I can’t really wrap my head around the moral purpose of Snow White, my question revolves more around The Sandman. Are children so hard to get to bed that they need to be threatened with a stranger barging into their room, stealing their eyes, and rendering them blind for the rest of their lives to do it?

In the folktale of The Sandman (not to be confused with the text we read), a child loses his eyes because he didn’t go to bed at the time his mother told him to. In The Little Red Riding Hood, for example, Red loses her grandmother and gets eaten because she talked to a stranger. I’m pretty sure we’ve all been told that if we held a funny face for too long, it would stick. Before I wrote this, I tried to think of a famous fable with a reasonable moral that didn’t use a fearful (and sometimes grotesque) threat against a child’s wellbeing to convey its moral across to its audience. I could only think of one, even in choosing to analyze the more modern version adapted for our own generation’s consumption. Why must we scare kids into doing what we know is best for them?

From experience, I know that children don’t always know what is best for them and after what feels like (or literally could be) hours, a caretaker usually just wants something easy for them to do and hard for the kids to ignore. A story is very easy to tell, and fear, at any age, is very difficult to ignore. Scary stories don’t need to be logical (wolves can totally pass off as grandmas), but they can still be just as effective. But how effective is it really? If we take the moral of Little Red Riding Hood we learn that we shouldn’t talk to strangers. But the older you get, the more surrounded by strangers you become. We see strangers as a step before acquaintances or even friends rather than wolves intent on harming us and our families. And if someone maintains the view that everyone is a wolf, they generally find it more difficult to adapt to the dominantly extroverted culture of today.

What I’m trying to say is that we grow up to learn that these stories were made to scare us into the actions they encouraged. Once we realize this, we end up talking to strangers, going to bed pretty late, and making funny faces all day long.

This got a lot longer (and a lot less organized) than I intended it to be, but I just wanted to also mention that not abusing children’s immaturity goes a very long way. The one fable I could think of that wasn’t scary, the tortoise and the hare, is still one that is relevant to my life today (Pace yourself. Be humble. Believe in your abilities. Focus on your own goals rather how close other people may be to reaching the same goals.). Sure, it takes a bit more effort to think of a story for children that meets the criteria of being interesting to children, morally relevant (even in the face of changing generations), and effectively serves its purpose. But in an ideal world, I’d much rather put my child to bed with a warm cup of milk than a nightmare.

Last week we covered a couple of children stories (Snow White and The Sandman) and one thing they definitely had in common is that they were both pretty creepy. Because I can’t really wrap my head around the moral purpose of Snow White, my question revolves more around The Sandman. Are children so hard to get to bed that they need to be threatened with a stranger barging into their room, stealing their eyes, and rendering them blind for the rest of their lives to do it?

In the folktale of The Sandman (not to be confused with the text we read), a child loses his eyes because he didn’t go to bed at the time his mother told him to. In The Little Red Riding Hood, for example, Red loses her grandmother and gets eaten because she talked to a stranger. I’m pretty sure we’ve all been told that if we held a funny face for too long, it would stick. Before I wrote this, I tried to think of a famous fable with a reasonable moral that didn’t use a fearful (and sometimes grotesque) threat against a child’s wellbeing to convey its moral across to its audience. I could only think of one, even in choosing to analyze the more modern version adapted for our own generation’s consumption. Why must we scare kids into doing what we know is best for them?

From experience, I know that children don’t always know what is best for them and after what feels like (or literally could be) hours, a caretaker usually just wants something easy for them to do and hard for the kids to ignore. A story is very easy to tell, and fear, at any age, is very difficult to ignore. Scary stories don’t need to be logical (wolves can totally pass off as grandmas), but they can still be just as effective. But how effective is it really? If we take the moral of Little Red Riding Hood we learn that we shouldn’t talk to strangers. But the older you get, the more surrounded by strangers you become. We see strangers as a step before acquaintances or even friends rather than wolves intent on harming us and our families. And if someone maintains the view that everyone is a wolf, they generally find it more difficult to adapt to the dominantly extroverted culture of today.

What I’m trying to say is that we grow up to learn that these stories were made to scare us into the actions they encouraged. Once we realize this, we end up talking to strangers, going to bed pretty late, and making funny faces all day long.

This got a lot longer (and a lot less organized) than I intended it to be, but I just wanted to also mention that not abusing children’s immaturity goes a very long way. The one fable I could think of that wasn’t scary, the tortoise and the hare, is still one that is relevant to my life today (Pace yourself. Be humble. Believe in your abilities. Focus on your own goals rather how close other people may be to reaching the same goals.). Sure, it takes a bit more effort to think of a story for children that meets the criteria of being interesting to children, morally relevant (even in the face of changing generations), and effectively serves its purpose. But in an ideal world, I’d much rather put my child to bed with a warm cup of milk than a nightmare.

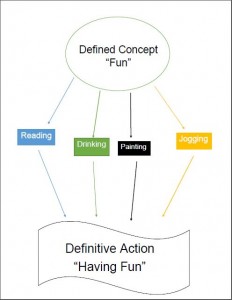

within our capabilities to discuss seems to always fall into a causality dilemma (like the chicken and the egg). So for you understand why I think this, I have to explain why I think the truth (or any concept) is objective and subjective at the same time. We start with a concept that is understood enough to gestate and further define, like the concept of fun. When fun is defined as something that is entertaining or pleasurable, this defined concept of fun is objective. However, because different people perceive the world differently, when the concept of fun is internalized, it comes to mean different things. For some it means reading, other drinking, others jogging etc. Even though all of these actions are definitively different, they are also still considered fun. So that, if, in the same room, a person was reading and another was dancing and a third was drinking, everyone in that room would be having fun. When everyone in The Fun Room is having fun, the definition of fun is relative to each person but also objectively defined as doing what it is they find entertaining or enjoyable. On a wider scale, if we look at initial objective definition of fun (the defined concept), we have to acknowledge that at one point this objective definition was a subjective one. Someone once decided that pleasurable or enjoyable things should be called “fun” and so they were when everyone adopted the objective definition and applied it subjectively.

within our capabilities to discuss seems to always fall into a causality dilemma (like the chicken and the egg). So for you understand why I think this, I have to explain why I think the truth (or any concept) is objective and subjective at the same time. We start with a concept that is understood enough to gestate and further define, like the concept of fun. When fun is defined as something that is entertaining or pleasurable, this defined concept of fun is objective. However, because different people perceive the world differently, when the concept of fun is internalized, it comes to mean different things. For some it means reading, other drinking, others jogging etc. Even though all of these actions are definitively different, they are also still considered fun. So that, if, in the same room, a person was reading and another was dancing and a third was drinking, everyone in that room would be having fun. When everyone in The Fun Room is having fun, the definition of fun is relative to each person but also objectively defined as doing what it is they find entertaining or enjoyable. On a wider scale, if we look at initial objective definition of fun (the defined concept), we have to acknowledge that at one point this objective definition was a subjective one. Someone once decided that pleasurable or enjoyable things should be called “fun” and so they were when everyone adopted the objective definition and applied it subjectively.