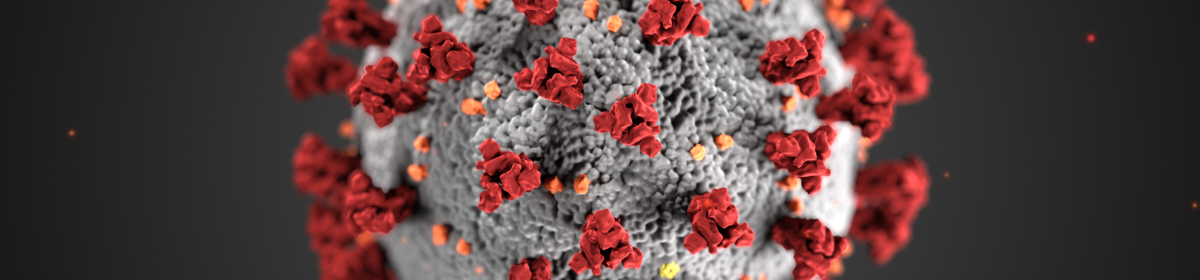

As this report is being created, in late April of 2020, mitigating the spread of COVID-19 is the number one global priority. The World Health Organization had been aware of a “pneumonia of unknown cause” since the end of 2019 (WHO, 2020), and while this new disease was quickly identified as COVID-19, it was not declared a pandemic until March 11, 2020 after it had spread across more than 100 countries (Brueck & Miller, 2020). As of April 28, 2020 there have been over 3 million confirmed cases and nearly 228,000 deaths globally (Dong et al., 2020), transmission rates that have not been seen since over a century ago during the Spanish Influenza where over a third of the world’s population was infected (Vocke, 2020). However, while the Spanish Influenza thrived off of health and young bodies, COVID-19 is prejudice towards the elderly and immunocompromised populations, which represent the vast majority of deaths (Dong et al., 2020). Being a type of coronavirus, a group of viruses that lead to upper respiratory infections, the severity of the COVID-19 situation is confirmed as two other forms of coronaviruses, MERS and SARS, have previously caused devastating pandemics (Stöppler, 2020). While there is still a lot of mystery revolving around COVID-19, what we do know is that it spreads by coming into contact with airborne germs from sneezing or coughing and its incubation period is approximately 5 days, but can take up to 2 weeks to fully emerge in about 1% of cases (Stöppler, 2020). Thus, the best mitigation practices have been frequent and thorough hand washing and maintaining at least 2 meters of social distance from others (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2020). The response by governments across the world to “flatten the curve” has been to close their borders to all non-citizens and over a third of the global population is under some sort of lockdown, from the national, to provincial, and occasionally even district level travel restrictions (Kaplan et al., 2020). International travel has mostly halted, but anyone who must travel across borders is also required to remain in self isolation for the entire potential incubation period of two weeks in most countries (Connor, 2020).

The impact of COVID-19 in Canada has been felt unequally across it’s provinces and territories. As of April 28, 2020, the total number of confirmed cases is 52,056 with 3,082 deaths, however, Québec disproportionally holds almost half of all confirmed cases and deaths (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2020). Within Québec, Montréal is a distinct hotspot with over 13,000 of the 27,500 cases and 1,150 of the 1,860 deaths in the province (Gouvernement du Québec, 2020), and at an even larger scale, the specific hotspots within Montréal are the long-term care homes for seniors (Kestler-D’Amours, 2020). There are several potential reasons for this geographical spread including population density and demographic combinations, slow and mismanaged government responses, chronic medical staff shortages in long term care homes due to underfunding and a heavy work load, and a lack of physical resources within care homes (Kestler-D’Amours, 2020; Lowrie, 2020). It has been continuously reported that there are bureaucratic hurdles or blockages for medical staff to assist or bring in supplies to these care homes and many who were working in long-term care facilities are not surprised by how the situation has unfolded (Kestler-D’Amours, 2020). Data pertaining to housing for long-term care homes is surprisingly vacant within both the official Québec and Montréal geodatabases, despite almost all other provinces, territories, and even the United States having detailed dataset. This is a good example of the neglect for senior health that the Quebec government has been continuously accused of during this time (Kestler-D’Amours, 2020; Lowrie, 2020).

This study looks to create a speculative vulnerability surface across the city of Montréal by using a ordinary least squares regression (OLS) on ArcGIS Pro for it’s citizens to assess their proximity to the riskiest areas. Using known high-risk demographic variables from the 2016 census, including population density, percentage of the population over 65, percentage of the population that is Jewish, percentage of the population living alone, percentage of the population who are low income, and the number of long-term care homes per census tract, several different vulnerability surfaces were created, pertaining to each variable. This report is speculative because it assumes that the centre for COVID-19 outbreaks are in long-term care homes and risk is generally likely to diminish as you move away from them, though there are exceptions. Although Montréal, like most other parts of Canada, has shut down all schools, daycares, and nonessential business, and have strongly suggested for everyone to remain at home except for necessities, this study will help Montréalers to make the best routing decisions for when they do leave their home.