Write a blog that hyper-links your research on the characters in GGRW according to the pages assigned to you.

I’m using the PerennialCanada 1999 version of Green Grass, Running Water, so I my assigned pages appear to be one page off at pages 99-114.

My section seems to be a mixed bag of everything.

It begins with First Woman and Ahdamn boarding the train to Fort Marion, where Ahdamn becomes famous for drawing pictures and the First Woman is forced to abandon him there to continue her journey with Ishmael and Hawkeye and Robinson Crusoe (we come back to this at the end of Hawkeye’s narrative, but it appears that abandoning Ahdamn was the real beginning of their journey) .

Ishmael takes over the story and here begins Changing Woman’s narrative. She watches her reflection in the water from Sky World every day, until one day she falls through the sky and lands on Old Coyote, who was sitting in a canoe.

Cut briefly to the four Indians. “Is that our ride?” Hawkeye asks. Later on in the novel, you may remember that this ride is Lionel’s car.

Then we get the first and only formal introduction to the Dead Dog Cafe. Latisha and her crew are getting ready for a group of American tourists, and they come up with a new name for the special. The narrator explains how Latisha turns her restaurant into a tourist trap.

Finally, we are introduced to Eli and Sifton and the whole dam situation (pun intended?).

Fort Marion

Courtyard of Fort Marion

In each of the four Indians’ narratives, they end up being captured and put into Fort Marion. It becomes a recurring theme buried other scores of other recurring themes. In history, the Fort Marion Prisoners were a large group of Plains Indians taken into captive for arbitrary reasons. Most of their offences were no more than simply being Indian, and the quarter or so women and children were simply there because they did not want their family to be separated. They were given western clothing (some of them cut off the lower part of the legs to make it a little more Indian). Later on, some of these men went on to become guards at Fort Marion.

Now we come to Ahdamn’s famous drawings! These drawings were basically pencil, ink, and watercolor drawings on old accounting books, also known as ledger. As such, they became known as “ledger drawings.”

These drawings were a way to memorialize the Plains Indian victories, and other aspects of their primarily oral tradition.

Here’s a quick thought:

This was presumably what Ahdamn was working on, except, of course, he isn’t really a Plains Indian as far as we know. They’d come straight out of Eden He draws a horse, a buffalo, and a refrigerator and becomes famous. This could be King’s way of showing us how little we understand the significance of these ledgers, and perhaps how simply we’ve been looking at them. It takes a lot of context, I believe, to fully understand each picture, and it feels like something very sacred to the preservation of Plains Indian culture. Something perhaps only Plains Indians will understand.

The Dead Dog Cafe

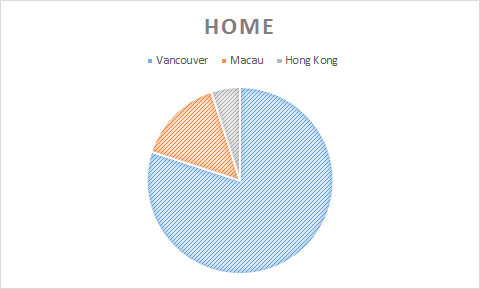

First, a word on tourist traps. When I went to Japan last year, my mom decided to have the most inauthentic tourist experience by booking a coach tour. I loathe those things, but they feel safe (to my mom), so we went along with it. Every stop is pretty much a tourist trap. They don’t even try to hide it on these tours. The food is pretty crappy, and there’s a gift store selling 600 yen mochi and Mt. Fuji shaped chocolates. There were a few nights where we got to explore the the locality on our own, so it felt a lot more authentic just by virtue of us having to struggle with the menu and seeking it out. If I’d wandered into the Dead Dog on my own, I would think I’m a brilliant adventurer if I didn’t see those postcards and menus for sale. In the same situation, if I’d come on a bus, I’d be pretty skeptical.

In Vancouver, there are a few Chinese restaurants my family avoid like the plague because my parents consider them tourist traps. One would think that perhaps the restaurants with the most non-Asians are the traps, but that is not always the case. What makes a tourist trap a tourist trap? Location? Hype?

I tried to find a Dead Dog equivalent on TripAdvisor. There are a great many resorts and lodges, like the Miccosukee Indian Village in Florida, boasting its Gator Tail Bites, Catfish Filet, and Fried Frog Legs. In Vancouver, we have the first Native American restaurant, Salmon N’ Bannock, serving up things like buffalo, elk, and boar. It has wonderful ratings, and a gift shop to match!

Thoughts?

In my opinion, these tourist traps are not necessarily intrinsically bad things. For one thing, where else would you find an elk burger locally? These places give you a taste of a culture that you may not normally approach. The only thing that usually sucks is the sub-par quality of a quantity over quality place. I think maintaining a bit of skepticism is a good thing in these cases. If it’s good, keep searching for better, and if it’s bad, keep searching for the good.

The Dead Dog is entirely a caricature of the tourism business, and a caricature of tourists trying to participate in the culture. In fact, King’s Dead Dog Cafe radio show on CBC even had an “Authentic Indian Name Generator,” which is unfortunately now defunct. Many Natives had very negative responses, to which the creator responded,

If you think about it, you realize most people have what we could call descriptive names. George W. Bush, for instance, probably got his name because one of his remote ancestors had some significant connection to a bush. But do we call him “Shrubberyson” or anything similarly mocking?

No, of course not. We don’t mock anybody for their descriptive names except Indians. Why do people belittle Indian names alone? Because they think it’s an acceptable way to feel superior to others. Because they can, in short.

I encourage clicking the Indian Name Generator hyperlink to read the dialogue!

The Dam

It appears that Eli’s dam conflict is a reflection of the Oldman River Dam conflict. There are possibly tons like this, but the location of the Dam, in Brocket, Alberta, is extremely similar to Balene Dam, Sifton’s dam project.

The purpose of Oldman River Dam was to help the south Alberta farmers with irrigation. The plan was drawn out over decades and was finally built in 1990. Among many other problems this dam faced, the Peigan Blackfeet fought to reclaim their land and move the project elsewhere, as the dam would have flooded ancient Peigan burial grounds. A group called the Lonefighters, led by Milton Born With A Tooth, retaliated by digging around the dam with an excavator. Born With A Tooth was arrested. You can read a bit about his story here.

In the end, the dam stuck around in spite of all the environmental and aboriginal concerns.

Thoughts:

The dam controversies, both Eli’s and Milton’s, seem to represent a centuries old tradition of disrespect, as the white farmers and businessmen will always be more important than any contract made with the Natives. Eli’s efforts spanned nearly a decade, and he ultimately goes down with it, as if his sole purpose was to protect his people against the oppressive nature of the dam.

Coyote’s involvement thus becomes rather interesting. It is as if it takes a Native figure to protect Native rights. Milton attempts to go around the dam in a non-violent way, just like Coyote, but real life is not so idea. Eli’s death, therefore, seems to be a reminder that nothing can be gained without sacrificed, especially in a system that do not privilege the Natives.

Works Cited:

“1874 US Infantry Private.” 1874 US Infantry Private. Tree Frog Treasures, n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2015.

Anonymous. Warrior with Shield and Lance While under Fire from Unseen Enemies. Digital image. National Anthropological Archives: Conservation of Anthropological Artwork. Smithsonian, n.d. Web. 12 Mar. 2015.

Eiselein, E. B. Fort Marion Courtyard. Digital image. Photobucket. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 Mar. 2015

Horn, Kahentinetha. “Milton Born with a Tooth on Campaign Across Canada.” Intercontinental Cry. Center for World Indigenous Studies, 07 Aug. 2006. Web. 13 Mar. 2015.

“Ledger Drawings.” National Museum of American History. Smithsonian, 13 Nov. 2009. Web. 13 Mar. 2015.

“Miccosukee Indian Village, Tamiami.” Miccosukee Indian Village (Tamiami, FL). TripAdvisor, n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2015.

Ojibwa. “Native American Netroots.” Native American Netroots. WordPress, 24 Feb. 2012. Web. 13 Mar. 2015.

Daschuk, James, and Gregory Marchildon. “Historical Chronology of the Oldman River Dam Conflict.” PARC (n.d.): n. pag. Prairie Adaptation Research Collaborative. Prairie Adaptation Research Collaborative, 1993. Web. 12 Mar. 2015.

Salmon N’ Bannock. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Mar. 2015.

Schmidt, Robert. “Stereotype of the Month Entry.” Blue Corn Comics. N.p., 10 Aug. 2000. Web. 13 Mar. 2015.