On Friday March 4th, I attended the Cutting Copper practice on Recognition, Refusal and Resurgence at the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery. In particular this event was in dialogue with the Lalakenis/All Directions exhibition currently showing at the gallery. Specifically, I witnessed Dana Claxton’s performance, along with the panel discussion held with Linc Kesler, Leanne Simpson, and Taiaiake Alfred.

Opening

The curators of Cutting Copper commenced the event by first acknowledging the unceded land of the First Nations people. With other opening remarks and thanks, Audrey was introduced on to the podium.

Audrey was involved in the cutting copper journey with Beau and other people from her community. She proudly introduced herself as individual doing work first for her ancestors, elders, the earth, and then for others.

To conclude the opening remarks of the event, Andrea sang the women warrior song as it was dedicated to women. She encouraged anyone who knew the song to sing along. When the song was sung, a strong aura filled the room and uplifted people. Proud voices rang through the gallery as I felt an immense connection with the women who were standing around me. The commencement with the women warrior song set a positive tone for Claxton’s performance and panel discussion as it “rejuvenated the seeds of feminine power”. (Smith, Me ARTSY)

Claxton’s Performance

Everyone in the gallery was asked to step outside of the gallery for Claxton’s performance immediately after the opening remarks.

Claxton entered the exterior space with a digitalized Indigenous song that had a similar rhythm to the women warrior song. The speakers were hidden in red blanket that was tied to her body. She had in her hands red twine. She began the performance by taken one end of the string that was attached to a chopstick and stuck it right outside of the gallery where the grass had begun. Claxton started to move along the grass while unraveling the string laying it gingerly on the ground. The big crowd too would follow behind her while intently observing her moves.

It was interesting to watch the UBC community collectively walk with Claxton as she led the large crowd. Particularly, I was engaged to how diverse the demographic was ranging from different faculties and backgrounds. I felt interconnectivity amongst the visual artists, art historians, anthropologists, and First Nation. Even though people observed Claxton, they too were engaged in conversing in dialogue with the people they were walking with. With such, we were all a part of Claxton’s performance where there was collective interaction in walking the perimeter of the gallery together but also engaging with our surroundings. In a way, I felt Claxton’s performance was the “UBC’s” or “our” journey. The red twine mimicked the Awalaskenis journey map.

After circling the perimeter of the Belkin, Claxton entered the gallery space. She began to wrap herself in a red cloth and later bobbed her body to the sound of the music. Claxton then unraveled herself, took the cloth by one arms length and she would rip it until there was nothing left. The ripping action was another element that Claxton has used in her pervious work in “Indian Dirt Worshipper”. She would fold them gingerly and give them as gifts, to the audience.

Panel Discussion

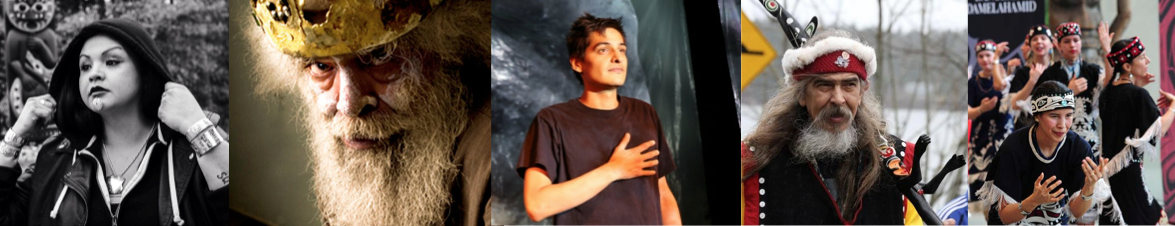

The panelists included Linc Kesler, Gerald Taiaiake Alfred, and Leanne Simpson.

Kesler is the director of the UBC First Nations House of Learning and Senior Advisor to the President.

Taiaiake Alfred is an author, educator and activist, born in Tiohtiá:ke in 1964 and raised in the community of Kahnawake

Simpson is an indigenous gifted poet, academic and musician.

In reference to the catalogue, “the panel would [spoke] of the theoretical interventions at play when considering the ways in which Indigenous people have sought to overcome the contemporary life of settler-colonization and achieve self-determination through cultural production and critique.” In particular, the panelists spoke of recognition, refusal and resurgence. They specified for the country’s futurity, Canada needed to be more indigenized for the better of the future.

“Refusal to be erased, Resurgence enactment, Recognition of the land.”

Overall, I felt a strong presence of First Nations women at the event – from Claxton, Audrey, Simpson and the people who were adding on to the dialogue from the panelist discussion which felt empowering.

Discussion Question: What do you think the procedure and process was for the protocol of the masks in the Lalakenis exhibition?

Google slides Presentation: https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1n56JpLbODQE6RHFabneXXEKPDlYBapmU5y72qu9r_D8/edit?usp=sharing