“REsolve is a courageous perspective of an individual, exploring thoughts and feelings, emotions and actions confronting corporate corruption and the destruction of our biosphere. In this dance we are observing from political cultures the perspectives and personal experiences of hopes, dreams and fears; exploring the thoughts, feelings, emotions and actions when confronted by an increasingly authoritarian system. However, with peace we share the insight of the internal thoughts and decisions of the individual forced to confront losing, one’s human rights and freedoms; participating with nature and fighting back or becoming the oppressors’ to death. But, also REsolveis to be at peace to overcome our present slavery physiological bondage; where you have no choice but to stand up for freedom; inspiring and moving at many levels, politically, culturally, regionally and intercontinental. REsolve inspires to address issues of de-colonisation of self, our tribal dances of spirituality, enhancing the bio connection to landscapes, plants, wildlife above and water, shape shifting and confinement, sexual abuse issues, racism and classism, and the codification of slavery, consumerism, and rural lifestyles, incorporating traditional and contemporary dance in solos, duets and quartets and original music for 30 minutes.” (From the Vancouver International Dance Festival performance catalogue.)

***

On Thursday the 3 March, I witnessed a 30-minute contemporary dance performance by the Ottawa-based Indigenous dance group Circadia Indigena, entitled REsolve. The piece was the opening performance for the 2016 Vancouver International Dance Festival (VIDF) and the preceding piece for the performance of Compagnie Virginie Brunelle (which played around 30 minutes after REsolve finished). The performance was held at the Roundhouse Exhibition Hall in Yaletown at 7.00 PM.

At around 6.30 PM my partner and I arrived, paid the $3 membership fee for the VIDF and entered the Yaletown Roundhouse Exhibition Hall. Blue lights illuminated a raised stage, in front of which were around thirty little round tables covered by black tablecloths and fake candles. Sushi, vegetables and dip, crackers and cheese, and profiteroles were available for free consumption. I observed the audience: they were mainly Caucasian (as far as I could tell) and over the age of 40, mingling and chatting as one would at an art gallery opening. I wondered how this chic soirée setting, surrounded by the VIDF’s annual art and photo exhibition, would contribute to how the witnesses were to view and absorb REsolve.

After introductions by Amanda Parris (host of CBC’s Arts & culture Program Exhibitionists) and the Co-producers of the VIDF, Barbara Bourget and Jay Hirabayashi, the performance began. Byron Chief-Moon* slowly entered onstage and faced away from the audience, holding a position that resembled shooting a bow and arrow and, twitching, crumpled to the ground. Jerry Longboat*, Luglio S. Romero*, and Olivia C. Davies* slowly entered from the sides of the audience and crept upon the stage. All four performers were wearing zombie-like make-up (white faces and dark eye sockets), and the men sported ripped business suits while Olivia wore a dress with red fabric cascading down the front. Olivia, Jerry, and Luglio squatted whilst Byron made motions of picking things up and dragged himself across the stage by his hair and clothes. The others then rose to join Byron in a circle dance, which was followed by a catwalk-like segment in which the dancers seemed to impersonate monster-fashion models. During most of the first half of the piece, the music was overlaid with a creepy voice performing an often-unintelligible monologue about exercising control over others. At one point, one of the dancers assumed the position of the standing cross, and the other three laid him down on the ground. This was repeated by two more of the dancers. At this point I could hear snippets of the monologue saying “we will guide them” and “we shall extinguish them”.

Soon afterward, Byron ran upstage and stared at the audience. The music stopped, and Byron proceeded to make a speech. He was echoed visually on a screen at the back of the stage on which was projected a live video of him (the cameraman of which was positioned in the audience)—this was reminiscent of the multiple-angle videos of people performing speeches on television. Ironically, the essence of Byron’s speech was “Turn off your TV!” “Television is not the truth,” he exclaimed, it is a circus, or rather a freak show. He advises us to “go to yourself; there you will find truth.” Throughout his speech the other three dancers approached Byron slowly, looking incredibly annoyed and threatening, whispering viciously. After a while Byron noticed them and yields his cause: “Okay. I said okay!”

The music resumed with a fast tempo and the dancers resumed their dance, this time echoed visually on the background screen, which multiplied their images and outlined the dancing figures with radiating colourful contours (perhaps reminiscent of the sensory overload of television). The lyrics of the songs spread clear messages: “We want your soul” and “America, your government is in control again”. Suddenly, each of the performers revealed some sort of sparkly or otherwise outrageous garment or accessory, and guest artist Su-Feh Lee entered the stage. She was dressed in a sparkly corset, fishnet stockings, and high boots, and she whipped an enormous bullwhip. Jerry longboat held out a large dark feather (as one may imagine a Medieval priest held out a cross to a person assumed of witchcraft). Nevertheless, all of the performers made beckoning movements accompanying the lyrics “We want your soul”. All of a sudden, the four dancers slumped to the ground. The music stopped and the lights turned off, and only the repeating crack of the bullwhip remained. When the lights were raised, the four dancers rose quickly and scattered to the opposite end of the stage from the bullwhipper. The five dancers then reassembled in center upstage and, smiling, took a bow.

REsolve was an incredibly confusing piece to witness, riddled with metaphorical imagery and hidden meaning. Possible interpretations that I had were as follows:

- The crosses laid on top of one another may symbolise the indoctrination of Christianity upon Indigenous Peoples and the consequent deaths of some Aboriginal cultures, traditions, and communities.

- “Turning off the TV”, in addition to an act of rebellion toward the accelerated and over-crowded superficialities of contemporary society, is also an act of decolonisation and Indigenous resurgence.

- The “circus” imagery painted in Byron’s speech is reminiscent of the old act of turning Indigenous people into side show attractions. This phenomenon inspired Monique Mojica’s play Side Show Freaks & Circus Injuns (produced by Native Earth Performing Arts), which she discusses briefly in her essay “Verbing Art” (in Me Artsy, page 27).

- The violent hushing of Byron’s speech by the others is an act of oppression against movements of resurgence and decolonisation.

- Su-Feh Lee’s bullwhip figure may represent an authoritarian system; this is emphasised by the others slumping to the ground, jumping up and scattering toward the opposite corner as they become overrun by the oppressor.

- We can spot small acts of resistance throughout the piece, such a Jerry Longboat’s feather and Byron’s more-or-less constant spirit of defiance.

As the audience was left to ponder over the meaning of REsolve, my partner and I exited the Exhibition Hall. Although confused and still digesting, we were certain that we had just witnessed a strong act of Indigenous resistance toward oppressive systems.

***

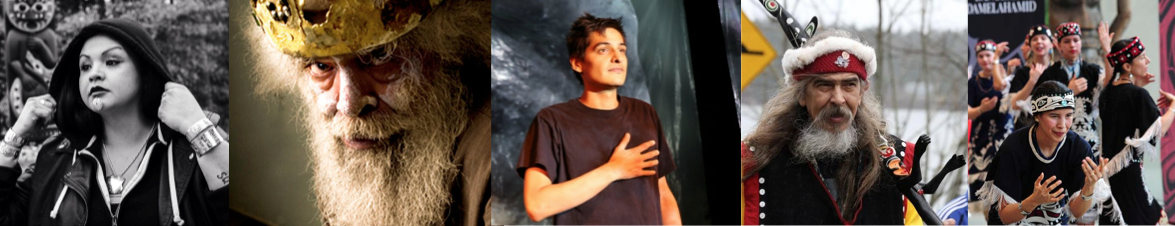

*Byron Chief-Moon is a Two-Spirit dancer and actor and a member of the Kainai Nation of the Blackfoot Confederacy in Southern Alberta. He was born in Carlsbad, California and now lives between Vancouver and Los Angeles with his family. His dance choreography combines traditional Blackfoot stories, dances, and songs with contemporary themes, dance, and music.

Jerry Longboat is the artistic director and founder of Circadia Indigena. He is Mohawk-Cayuga, of the Turtle Clan, from the Six Nations of the Grand River in Southern Ontario. He is a visual artist, graphic designer, actor, storyteller, dancer, and choreographer and has performed with professional dance companies across Canada.

Luglio S. Romero was born and raised in Costa Rica and studied Dance &Latin American Studies at Simon Fraser University. He has performed as a professional member of ballet companies in Costa Rica and BC, and he now teaches Zumba in Vancouver.

Olivia C. Davies is of Aboriginal heritage and studied dance at York University. She co-founded the MataDanZe Collective, a project aiming to empower women through movement. She is an Apprentice with the Dancers of Damelahamid and has choreographed performances for numerous festivals around Canada.

Su-Feh Lee is a Malaysian dancer/choreographer and the founder of the Vancouver-based dance company battery opera.

Visit Circadia Indigena’s website here: http://circadia-indigena.com/

Read the horrible review that I discussed in my class presentation here: http://www.vancouverobserver.com/culture/dance/demalahamid-and-circadia-indigena-dance-first-nations-experience-old-and-new

Lastly, here are some questions that witnessing REsolve provoked for me:

1)How might the setting (the tablecloths, fake candles, sushi and profiteroles, etc.) have played into how the attendees witnessed the evening’s performance of REsolve?

2)In her essay Verbing Art, Monique Mojica discusses “playing Indian” as a perpetual stereotypical role for mainstream Indigenous performers. She writes, “Our choices are either to put ourselves at the mercy of the artistic vision and politics of non-Indigenous directors, playwrights, artistic directors, designers and public relations machines and to stalwartly try to affect change from within those institutions, or to struggle to create [our] own theatre where our Indigenous artistic visions are in control and we unapologetically hold power over our voices, our stories and our images” (from Me Artsy, page 23). How does Circadia Indigena communicate this issue in REsolve? Additionally, how does the group maintain power over their own artistic visions and voices to change the common view of Indigenous performance art?