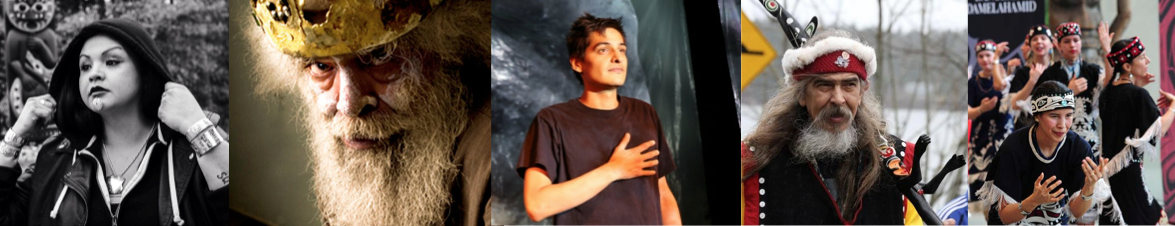

In late March, I attended the Vancouver International Women in Film Festival, to watch a small selection of female-produced short films under the heading “Compelling Characters”. Within this selection, I saw Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers’ beautiful piece, Bihttoš. Worth noting, Tailfeathers was the only Indigenous filmmaker featured in this selection, and one of few performers/directors of colour.

Tailfeathers is Sami (on her father’s side) from Norway, and Blackfoot (on her mother’s side) from the Kainai/Blood Nation in Alberta. She attended VFS for acting and later UBC to pursue a dual degree in Women’s and Gender Studies and First Nations Studies. She uses her films as a form of activism to shed light on topics such as land abuse (in Bloodland), violence against Indigenous women (in Red Girl’s Reasoning) and here, in Bihttoš as a means of addressing intergenerational trauma left behind by residential schools (and their equivalents) and the resiliency/survival of Indigenous peoples

Tailfeathers embarked on this film as a result of her involvement in the Embargo project which challenged her to write a story about her family. Bihttoš is the result of a years’ worth of conscious effort, and a lifetime of lived experience and growth.

Bihttoš, which examined in particular, Tailfeathers’ relationship with her troubled and formidable father Bjarne Store-Jakobsen, was divided visually and narratively into thirds.

The first, appearing in animation and narrated by a young Elle-Máijá, depicted her parents’ fairytale-esque love story. They met in a bar in Australia, both attending an Indigenous Rights conference as Sami and Blackfoot activists. Her father fell in love with her mother, Esther Tailfeathers, at first sight, and would travel across an ocean to profess his love for her.

The second, appearing in archival photographs and dramatic reenactments detailed Elle-Máijá and her family’s move from Sapmi when she was 5, to North Dakota to support her mother in pursuing her MD. This segment also detailed Tailfeathers’ and her brother’s means of adapting and struggling with the shift in their lives and in their parents, notably in her father, who fell into a deep depression and began to abuse alcohol. Tailfeathers noted that she often felt obliged to support her father as his confidante and felt the need to keep her family together.

This was unsuccessful, and following her mother’s decision to leave her father, Store-Jakobsen attempted suicide. Tailfeathers at this time was 16. Following this, Tailfeathers and her father went without contact for 9 years.

After this period, they reconnected via an 8000 km cross country road trip. This final third of the movie is comprised of Elle-Máijá’s own personal footage of the trip. A few years after this reconnection, Store-Jakobsen opened up to Elle-Máijá about his experience at Sami boarding school; until this point he had been unable to confess his experiences to anyone, and had coped by fighting valiantly for Sami rights.

In response to this admission, Tailfeathers found relief from much of the emotional struggle she had been both consciously aware of and things she hadn’t realized were weighing on her until that moment. She was able to find incredible compassion for both of her parents’ experiences, and chose to forgive them for not being able to love one another, and for not being the shining, perfect gods that we all tend to imagine our parents as being.

I would like to tie into this film Karyn Recollet’s notion of radical decolonial love; which encompasses all types of love romantic and otherwise between all peoples. Tailfeathers’ parents demonstrate tremendous RDL; her mother became an MD to finish the work of her older brother who had died not long before, in the midst of pursuing his own MD, her father fought for and secured government recognition of the Sami as Indigenous peoples in Sweden and Norway, Elle-Máijá herself creates films out of love for her own people, the land she belongs to, and Indigenous women across Turtle Island, she was able to find forgiveness (a deeply difficult and powerful act of love) for her father and understand her parents as imperfect people and not just as her caregivers.

I would also like to mention Ric Knowles’ concept of remembering as a tool for healing along with Recollet’s notion of colonial weight, as connected to intergenerational trauma incurred from the residential school system and its genocidal equivalents. Store-Jakobsen’s act of remembering his painful, and traumatic experience to Elle-Máijá lifted a portion of the colonial weight from his body that he had been carrying since he was a child. By virtue of her connection to him, and the traumas she herself carries in her body as a result of his experiences, Store-Jaksobsen’s remembering also lifted this colonial weight from Tailfeathers.

This concept blurs nicely into Monique Mojica’s concept of mining the body for organic texts as well. Elle-Máijá’s acts of remembering, delving deeply into her childhood memories and also the experiences of her parents, and examining the physical and emotional sensations that arose of these processes resulted not only in the beautiful story she has shared, but also in the furthering of her own healing process.

More widely, her opening this vulnerability to a broader audience allows for others in similar positions to examine their own connections to land, family, and themselves, perhaps catalyzing the healing processes of many more people to come.

I would like to leave you all with the following:

A link to the first portion of the film: https://vimeo.com/111828006

A brief and problematic review of Bihttoš by Addison Wylie, a non-Indigenous professional film critic trained in television broadcasting and film production: http://wyliewrites.com/canadas-top-ten-film-festival-14-shorts/

(Wylie seems to completely miss the point of the film, focusing mostly on aesthetic choices that Wylie feels were “risky” or amateurish)

Another brief but significantly kinder review by Joy Fisher a Victoria based playwright: http://coastalspectator.ca/?p=4071

(Fisher acknowledges the traumatic results of government sanctioned modes of ethnic cleansing and lauds Tailfeathers for her skilled storytelling. I wonder if Fisher is able to empathize with/better understand the story because of her position as a woman and the female tendency to emotionally caretake)

A brief note, it was quite difficult to find even a handful of reviews for this film although it was released in 2014. Those that I could find were quite brief, and often provided in a batch with brief reviews of other related films.

Question: How can we explore the notion of blood memory and organic texts as a means of furthering our own scholarship as Native and non-Native students and as a means of fostering collective healing and growth?

*by this I mean, engaging in connection to both the land we occupy and ourselves, mining our physical sensations and experiences and emotions that are called up as we mine these experiences.