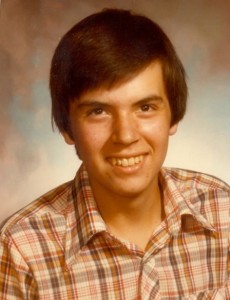

David: ‘When I got that ticket to Toronto it was freedom’

When he was 15, David Kirk left home on the West Coast and hopped on a Greyhound bus headed for the other side of Canada.

“When I got that ticket to Toronto it was freedom,” recalls David, who had been living in Burnaby, British Columbia, at the time. The year was 1978. He spent four full days and nights on the road before arriving out East with a duffel bag he’d bought the morning before the bus trip.

“I was a bit scared and yet, it was freedom,” he says, eyes creased and smiling overtop a grey goatee. The trip propelled him on a lifelong journey to discovering himself and his First Nations roots. “I just decided I needed to explore who I was as a Two-Spirited person and I wasn’t comfortable doing that. So I left to Toronto where I could be free and figure out what that meant.”

By running away as a teenager, David joined a group of young Aboriginals whose families push them out of their homes for not being straight. A 2006 survey carried out by the McCreary Centre Society found that Aboriginal youth who are gay, lesbian, bisexual and questioning their sexuality make up 34 per cent of Aboriginal homeless young people in British Columbia. In comparison, a provincial survey of teens in schools showed that 15 per cent of Aboriginal boys and as many Aboriginal girls identified the same way.

Some of these young people call themselves Two-Spirit, an Aboriginal name for individuals who would be considered gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgendered by Western standards. Two-Spirit however focuses more on Aboriginal spirituality and tradition instead of revolving around sexual preference.

Listen: David: “I needed to explore who I was as a Two-Spirited person” (1’00”)

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

A new name

The term Two-Spirit was created in 1990 at the third Native American/First Nations gay and lesbian conference held in Winnipeg, Manitoba. While different tribes have their own traditional names for people who break from conventional gender roles, Two-Spirit was devised to unite gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender Aboriginals.

“To me, it means that people’s gender identity is much more complex than what a colonial view is today in the Americas,” explains Albert McLeod, a Two-Spirited man who was part of the movement that coined the name. “Historically, you find among indigenous groups around the world there were concepts of third genders.”

Holding multiple meanings that can vary by nation, one definition describes a Two-Spirited person as someone who embodies the presence of both a male and female spirit. Before colonization they fulfilled special roles in their communities, including caring for children and acting as medicine people. That changed in the 19th century when residential school programs punished Aboriginal children for speaking their language and forced them to stop practicing their culture.

“The impact of residential schools has been one of silencing,” McLeod says. “It extends across generations now where a lot people today don’t speak their language, so how can you transfer cultural knowledge that is based in the language when you don’t speak the language?”

“Naming and renaming is a liberation process,” he continues, speaking about why the term is important. “It opens the door for discussion and exploration.”

Finding culture

David spent eight months in Toronto partying, couch surfing and sleeping in a shelter before returning home and telling his family he was gay. They sent him to a psychiatrist to try and turn him straight. When that failed, his family cut off ties with him completely.

“I mean I was part of a family for 15 years and basically was kicked out of the family and told never to come back for being gay or Two-Spirited,” David says, his voice losing steam. “They just closed the door and said, ‘Don’t call us. We don’t want to hear from you, we don’t want to see you. Goodbye.’”

David moved out again and couch surfed at friends’ places. Through working as a dishwasher and a waiter, he was able to afford a place when he turned 18.

Living in downtown Vancouver in the 1970s and 1980s, he’d see Aboriginal boys working as prostitutes in the warehouse district. The area was gentrified during the 1990s to become the upscale neighbourhood of Yaletown. But David continued to spot these boys picking up dates at the street corner of Drake and Homer. Seeing part of his struggle in them, David started a drop-in for Two-Spirited and queer First Nations youth in the sex trade in 1995 that lasted three years.

“I could identify with the youth that I was working with in their struggles of coming out and their struggles with being rejected by their families,” David says. “They’d left their communities because of the stigma of being gay or Two-Spirited.”

Listen: David: “There’s a lot more homophobia within some First Nations communities now” (1’10”)

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

In 2010, 29 per cent of the male sex workers in Vancouver identified as First Nations or Métis, according to the yearly evaluation carried out by the sex worker outreach and support program Hustle: Men on the Move. A 2005 survey led by researcher Sue McIntyre found that 43 per cent of young men in British Columbia’s sex trade were Aboriginal. The statistics reflect the number of individuals who could be found accessing services and were willing to share their experiences. Many are hard to spot due the perception that men don’t sell sex and because they may also avoid using support providers.

“When you are 15 or 14 or 13 and you are out on your own and you have no work experience you can’t get a job,” David says. “So what do you turn to? The sex trade.”

David’s drop-in group would meet once a week, attracting between 4 and 20 Aboriginal youth a night.

“There was nothing else out there,” he says. “And I was starting to realize that the street-entrenched youth who were Two-Spirited weren’t using mainstream drop-ins.”

First Nations Elders taught them about their cultural histories as well as the sacred roles of Two-Spirited people. Field trips took the teens outside of the city and into nature. There they’d learn about traditional medicines and participate in smudging ceremonies by burning sage to cleanse away negative energy.

“They just had this hunger for knowledge and for traditional teachings,” David explains. “We’d have a picnic and share food and laugh, and they could forget about worrying about pulling their next trick.”

Coming out on top

Nearly in his fifties, David now works as a First Nations advisor at a North Vancouver university. Holding a degree in social work and finishing up a master’s in adult education, he contemplates whether or not he has the time for a PhD.

“I would continue my research around cultural identity and Aboriginal learners, because I think there is a really strong connection,” David says as he sits under the hot sun by his community garden plot, just blocks away from the apartment he and his partner share. He believes Aboriginal students with stronger ties to their heritage are more likely to succeed in life.

“I could have turned out a lot differently,” David realizes as he looks back on the time when he didn’t have a home or a family. “I could have let my past dictate and I could have said, ‘Poor me, poor me. I’ve been hard done by. I’m never going to amount to anything. Why bother trying?’ It did the opposite, it’s like, ‘Well screw you.’”