They say that any endeavor worth doing requires a good deal of work and resilience, and this project surely fell into that category. After several months of planning, we delivered a workshop at the Grandview Woodlands Food Connection (GWFC) to investigate the perspectives of the ultimate users, the youth members of the Teen Center, on the proposed conversion of a decorative garden to a food garden.

Executive Summary

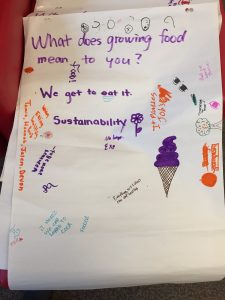

The Grandview Woodland Food Connection (GWFC) is a Neighbourhood Food Network that works to improve food access and sustainability in the neighborhood surrounding the Britannia Community Centre (Grandview Woodland Food connection, n.d.). Our project was designed to complete the first phase of a garden transformation project facilitated by the GWFC at the Britannia Teen Centre (BTC). Our project’s contribution was to ascertain the perspectives of the youth who attend the BTC and are intended to be the end users of the food garden. We held an in-person workshop with the teens, splitting them into four groups, each sitting with a poster featuring an open-ended question. The teens added their responses to the posters (as shown below) throughout a facilitated five minute response period.

The results showed that the teens at the BTC both want a food garden and are keen to be involved in garden operations. The GFWC can now move forward with the next steps of their garden transformation with a better idea of how to involve their teen stakeholders, improve teen food sovereignty and ensure the results of the project align with the teens’ needs and wants.

What

15 youth attended the session, which exceeded our expectations. We conducted an icebreaker activity to help ensure the youth were comfortable in the space and and then split the group into 4, each with a piece of poster paper and pens. We then asked the teens a question about the garden, facilitated a 5 minute discussion and asked them to record their responses on the poster. The groups cycled through each poster so that we received responses from all of the youth to all of the questions. We concluded the session by serving pizza and conducting a draw for a pair of movie passes.

So What

Our data collection session was taking place quite late in the semester, which meant we wouldn’t have any time to try again if anything went wrong. Not having worked with teens before, we were concerned that we might not be able to collect sufficient data for our final project. However, the session and the results it generated exceed our expectations and will serve us well in the week to come for our infographic and report.

We hope the results will also help our community partner implement their garden project. We feel that the approach we took aligns with the iPES-FOOD (2015) report that emphasizes involving the viewpoints of a diverse group of stakeholders and ensuring that project proposals are context specific. The report suggests that the traditional top down implementation of sustainability projects is unable to address complex problems and that gathering perspectives from all kinds of experts, especially those in the community, will lead to improved outcomes.

Our report helps address some of the knowledge gaps that existed in the realm of what teens would want from a food garden and hopefully will simplify the task of including teen perspectives in this project. We feel confident that as a result of this project, the GWFC will be able to proceed in a fashion that ultimately engages youth in a way that improves both their food sovereignty, food access and also educates them about their food system.

Outside the project, we’ve all learned valuable skills about working in groups, working with teens and working with community partners. As the Power & Privilege course (n.d.) taught us, disagreement between how a group sees itself and how others see it can lead to conflict. We feel we did a good job of defining roles for our group and the GWFC, they being the subject matter experts while we were responsible for planning and execution, which promoted a harmonious working relationship.

Now What

Despite cautions about the difficulties of working with community partners and teen groups, we were pleasantly surprised by how our interactions went. The GWFC was responsive, flexible and provided wonderful guidance on how we might best work with their teen audience. We were concerned that the teens might not be interested in attending a workshop about food gardens, and even if they did show up, that they might not be willing to share their thoughts. However, attendance was great and they appeared to be very engaged with the content. We agreed that this experience has made us more likely to engage with community groups in the future.

We also leave this project with a more tangible sense of the flaws with the “food-is-a-personal-choice” narrative alluded to by Dixon (2014). The paper argues against the notion that people merely need to be educated about healthier food choices to eat healthier, instead highlighting the systemic barriers (like cost) that prevent them from being able to make that choice. Responses to questions indicated that many of these teens faced hunger on a regular basis (as shown below). These teens were also clearly aware that they should be eating healthier, and wanted this garden to help make that happen, but due to a variety of limitations, are unable to make that diet a reality. This has made a lasting impression upon us in terms of the awareness of how little control the less fortunate wield over their diet and food circumstances.

References

iPES-FOOD. (2015). The New Science of Sustainable Food Systems: overcoming barriers to food system reform. International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems. pp.1-17.

Dixon, B. A. (2014). Learning to see food justice. Agriculture and Human Values, 31(2), 175–184.

Engaged Scholar: Module 2 – Power & Privilege. (n.d.). University of Memphis