For this assignment, I will be illuminating some of the allusions contained within pages 230 – 241 of the 2007 reprint of Green Grass, Running Water by Thomas King. The characters that figure most prominently in this section are the four “old Indians” (365), as King terms them, and Lionel Red Dog, Dr. Joseph Hovaugh, and Babo Jones. For the purposes of this post, I am going to focus on the four old Indians and Lionel Red Dog so that I can go into detail while making connections between pages 230-241 and the rest of the novel as a whole.

The four old Indians are one of the central mysteries of Green Grass, Running Water, and my understanding of them was limited during my first reading. After being assigned my section, however, I worked through the book again trying to understand the role that they play, and thankfully I gained some clarity.

The character of the Lone Ranger within the world of Green Grass, Running Water is in actuality First Woman from First Nations creation stories (who is also sometimes called Sky Woman), and on page 71 First Woman adopts the identity of the Lone Ranger in order to avoid impending violence at the hands of other rangers. She retains the alter-ego, as it also allows her to escape from the prison for Indians at Fort Marion; and thematically this resonates with other material in the novel that shows aboriginal people oscillating between whitewashed identities and embracing their cultural heritage as they navigate the rough social waters of colonial North America.

The others of the four old Indians are Ishmael, Hawkeye, and Robinson Crusoe. Ishmael is in fact the Navajo deity Changing Woman, and, like First Woman/the Lone Ranger, she becomes Ishmael for the protection that identifying as a male hero of Western literature offers her (King 225). In the same way, Robinson Crusoe is Thought Woman and Hawkeye is Old Woman, while Thought Woman is originally a figure from Navajo creation stories and Old Woman hails from First Nations tales generally (Flick 159, 161).

Throughout Green Grass, Running Water, these four women tell each other their origin stories as they simultaneously try to “fix the world” (King 236). At first I found this very confusing, but then I realized that their actions and their stories are one and the same, and that each time one of them begins a story a landmark in the timeline of their group’s mission to Canada is reached. When the Lone Ranger begins her story with “Gha! Higayv:lige:i” (a saying which shows that this is the beginning of a world-fixing cycle, because repeating it is deemed unnecessary on page 234), the four old Indians arrive in Canada (15, 22). When Ishmael begins her story, the group meets up with Lionel and gets into his car (104, 106, 121). When Robinson Crusoe has her turn, Coyote turns on a light to guide the Indians to the site of their intervention – the dam (231, 233); and when Hawkeye tells what happened to her, the four set out across the prairies to complete their task (327-28, 332-33).

The reason that it works this way is because Thomas King is trying to communicate to his readers that stories are an extremely powerful means of shaping the world. Origin stories, in particular, determine our world views; and in order to change society – to “fix the world,” as it were – stories that have been the root causes of problems must be altered, corrected, or retold in the right way. Also, the corrected stories must be told over and over again in order for them to take effect (hence the four old Indians taking turns and repeating their cycle again and again, as indicated on page 9 and page 430).

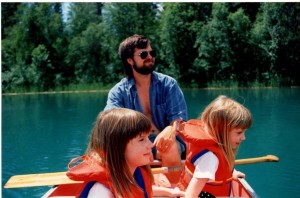

This is one of the jackets that John Wayne wore in film.

Lionel Red Dog personifies the sort of change that the four old Indians are trying to achieve. He is at the centre of their mission to Canada, because his sense of self has been confused by colonizing narratives ever since he was a little boy. As a child, he swallowed the lie that John Wayne is the best role model a kid can have, and as a result he has spent most of his life unable to connect to his cultural heritage, to his family, or to his true self (241-243).

The Indians meet up with Lionel partly to deliver to him a fringed leather jacket (they mention it on p. 234), as this gives him the chance to look and feel like John Wayne for a moment and to realize how ill the image fits him. Then, after noticing that the jacket smells rotten, and finding out that its true owner is George (a wife battering exploiter of First Nations culture, and a reference to General George Custer), Lionel willingly gives up this marker of identity and is able to enjoy a moment at his reservation’s sun dance with Alberta Frank, the woman he loves (382-88). This is something like a rite of passage for him.

As I mentioned, though, I couldn’t possibly cover all of the references between pages 230 and 241 of Green Grass, Running Water in any detail while staying under 1000 words. There are many more interesting allusions to be discovered, and while I hope that I haven’t passed over any of your favourites, please feel free to comment below and expand the discussion! I researched the contents of this section of the text thoroughly and I would be happy to engage in a dialog.

Works Cited

“Character Analysis: Ishmael.” Cliffs Notes. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. N.d. Web. Mar. 16, 2015. <http://www.cliffsnotes.com/literature/m/mobydick/character-analysis/ishmael>

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161-162. (1999). Web. Mar. 16, 2015. <http://canlit.ca/pdfs/articles/canlit161-162-Reading(Flick).pdf>

“John Wayne Biography.” Encyclopedia of World Biography. Advameg. N.d. Web. Mar. 16, 2015. <http://www.notablebiographies.com/Tu-We/Wayne-John.html>

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Toronto: Harper Collins, 2007. Print.

Neuhaus, Mareike. “That’s Raven Talk”: Holophrastic Readings of Contemporary Aboriginal Literature. Regina: U of Regina P, 2011. Google Books. Web. Mar. 16, 2015. <http://bit.ly/1Fs4qVm>

Roach, David. “Hawkeye.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica. Aug. 7, 2013. Web. Mar. 16, 2015. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/1938296/Hawkeye>

“Robinson Crusoe.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica. June 6, 2013. Web. Mar. 16, 2015. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/505784/Robinson-Crusoe>

Smith, B. R. “The Lone Ranger.” The Museum of Broadcast Communications – Encyclopedia of Television. Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity. N.d. Web. Mar. 16, 2015. <http://www.museum.tv/eotv/loneranger.htm>

United Artists. A John Wayne Jacket from “The Alamo.” 1960. Heritage Auctions, Dallas. Heritage Auctions. Web. Mar. 16, 2015. <http://bit.ly/1bcFu9s>

Urwin, Gregory J. W. “George Armstrong Custer.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica. July 21, 2014. Web. Mar. 16, 2015. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/147393/George-Armstrong-Custer>

“Woman Who Fell From the Sky.” Myths Encyclopedia. Advameg. N.d. Web. Mar. 16, 2015. <http://www.mythencyclopedia.com/Wa-Z/Woman-Who-Fell-From-the-Sky.html>

Recent Comments