Connecting the Stories in Green Grass Running Water

PAGES 207-217, 2007 Edition of Green Grass Running Water

This section concentrates on Charlie’s childhood when his father brought him to Hollywood, as well as explores more of his father’s experience of Hollywood. Throughout the second part, the narratives are connected either through the viewing of the same old Western, or in Eli’s case, the reading of a novel that is interchangeable with the Western on the television. The televised Western parallels with the various narratives in this section as it becomes a unifying narrative of the oppression of Indigenous people, their stereotyping reflected in both reality and the fantasy of the film and novel, the re-focalization on the white, European hero, as well as the potential loss of land due to Western expansion. The Western film takes on personal significance to Charlie when it is revealed that the man playing the chief is Charlie’s father.

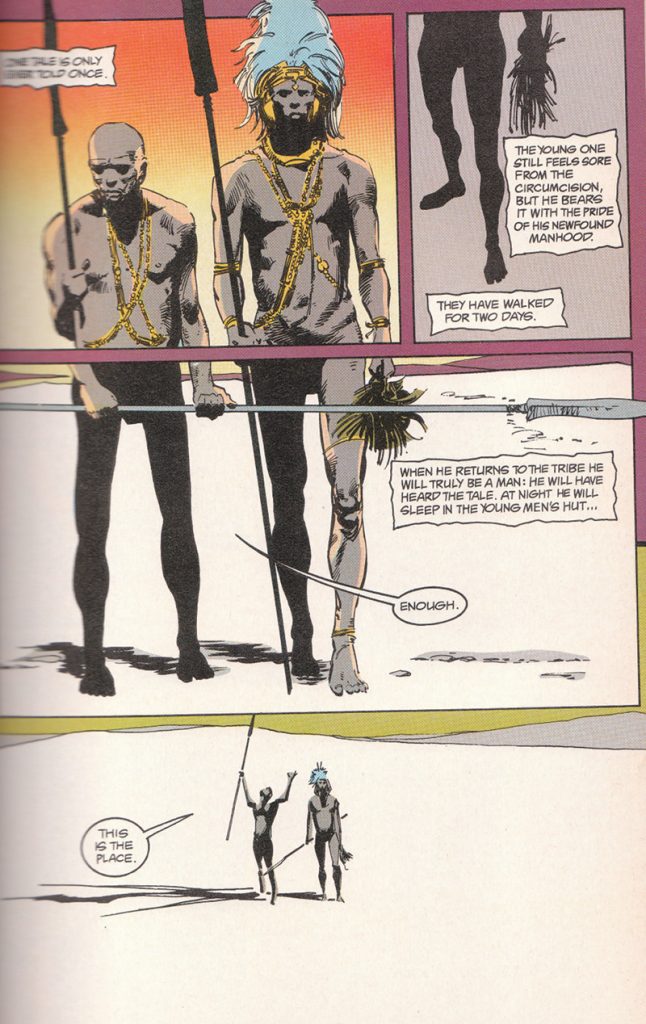

The Mysterious Warrior

Throughout this section, the film being viewed in unison by the characters of Green Grass Running Water, is the unifying thread that ties them all together. While the Western film works as a unifier in this section, it also draws individual meaning from each of the characters. For instance, Eli is reading a novel that runs parallel with the film in which he sees his possibly doomed romance with Karen. Bill Bursum, who identifies the film as The Mysterious Warrior, sees it as “the best Western of them all” (King 188) and heavily identifies with the invading John Wayne and his decimation of The Indians. Lionel, who also idolizes John Wayne, falls asleep to the Western. The four old Indians intrude the on-screen narrative, but “Lionel saw none of this,” (King 216) which is indicative of his unwillingness to participate in familial and cultural practices. He falls asleep to this Western, passively viewing the film much as he passively deals with his life by avoiding change.

In Jane Flick’s notes for Green Grass Running Water, she notes that The Mysterious Warrior is “a composite of Western films . . . This title alludes to The Mystic Warrior (1984), a television movie based on Ruth Beebe Hill’s Hanta Yo (1979). This novel ignited a firestorm of protest from Native American groups outraged by misrepresentation of the Lakota Sioux” (Flick 158). Here is a link to The Mystic Warrior, if you are at all interested in that. Flick also notes that John Wayne “did play one or two roles sympathetic to Indians,” (147) but the bulk of his career featured him as a character that indulged the prejudice towards Indigenous people and reinforced negative stereotypes. As Indigenous people were often portrayed as villains, or at least opposing forces in these films, the John Wayne white, European hero expressed hatred and racism towards the Hollywood version of Indians.

As a result of this deep-rooted racism where Indigenous people were never allowed to have the victory that John Wayne did, the characters in Green Grass Running Water are not surprised by the eventual outcome of The Mysterious Warrior.

Alberta hit the Off button. Enough. The last thing in the world she needed to do was to watch some stupid Western. Teaching Western history was trial enough without having to watch what the movie makers had made out of it. (King 214)

Portland Gets a Job at Remmington’s and Four Corners

From page 207-213, Charlie remembers his time in Hollywood following the death of his mother. This is the concluding section of his childhood memories, Portland and Charlie must finally get jobs at Remmington’s, in hopes of getting exposure and, therefore, an acting job. Portland sinks farther from his dream when he gets a job at Four Corners, which signifies the last straw before Charlie decides to return home without his father. Firstly, I will be addressing the allusions in accordance to Jane Flick’s notes and then I would like to discuss further connections outside of the novel, as well as relate it back to the framing of the Western film.

Remmington’s: This is the Western style bar that Portland, and Charlie, begrudgingly goes to work for when he is unable to get acting work on his own. The name is a reference to Frederic Remington, “the most famous artist of the Old West” (Flick 157). According to Flick, while his work glorified the setting and heroes of the Old West, Remington’s “depiction of Indians is essentially hostile” (157). This double standard is reflective of the segregation between Cowboys and Indians as, respectively, waiters and valets. Portland encourages Charlie “to grunt . . . the idiots love it, and you get better tips,” (King 209) which makes him a willing participant in the racial divide. Again, the contrast of Cowboys and Indians refers back to the framing device of the Western film where Cowboys and Indians are further divided into Heroes and Villains.

Four Corners: The Four Corners in the burlesque theatre that Portland eventually goes to work for. At the Four Corners, Portland is employed to do background dancing for an erotic dancer. In this cheap imitation of acting Portland so desperately wants to participate in, King again utilizes the trope of Cowboys vs. Indians. In the Green Grass Running Water notes, Flick says that the club is named for “the Four Corners area of the Southwest is the point at which Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah meet. It is an area of particularly rich cultural associations” (157-158). The name connects both to the motif of direction that is utilized throughout the novel, as well as the cultural appropriation underline in the Pocahontas routine.

Four Corners becomes symbolic of Portland’s ultimate “rock bottom.” This section of the novel concentrates on characters remembering old failures, or the failures of relative. For Alberta, she remembers her alcoholic father. Eli remembers his past lover, Karen, and ponders over his unwillingness to include her in his “Indian” life. Lionel, ever a build-up of his past mistakes and failures, has his final sleep before he attempts to change himself in the next section. Portland is stuck in his old dream of becoming a famous actor, a failure that Charlie refuses to replicate, to the point where he is willing to sexualize himself to achieve his dream.

While this article is not directly related to the novel, and also focuses on the sexualization and violence towards black women, I believe that many of Crenshaw’s observations apply. Crenshaw discusses the sexualization of racialized women as seen in pop culture, from film to video games, through intersectionality. Intersectionality asks us to analyze by considering various forms of criteria, as opposed to a static analysis. In this case, Crenshaw looks at sexualization through the lense of both race and gender, wherein racialized women take on an assumed sexual availability.

[On the portrayal of a Native American woman in General Custer’s Revenge] The Native American woman is a savage. She has no honor and no integrity. She doesn’t fight rape; in fact, being tied up and ravished makes her smile. She enjoys it. (Crenshaw 253)

By allowing himself to be sexualized, Portland conforms to European assumptions and stereotypes of his race. This relates back to the Western, which is re-enforced by racist attitudes and beliefs, wherein actors must conform in order to participate. This pressure to conform is echoed throughout the novel. Though Charlie strives not to conform in the way that his father did in Hollywood, he works at the same law firm that is attempting to remove Eli, who is also being pressured to conform to what the company wants, to utilize the dam.

Works Cited

“The Mystic Warrior: Qarwayaku.” YouTube, uploaded by Craska1, 19 Nov. 2014, youtube.com/watch?v=8TGRxP2alrg.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé Williams. “Beyond Racism and Misogyny: Black Feminism and 2 Live Crew.” Feminist Social Thought, edited by Diana Tietjens Meyer, Routledge, 1997, pp.247-263.

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass Running Water.” Canadian Literature, vol. 161-162, 1999, pp. 140-172. Freely Accessible Arts & Humanities Journals, canlit.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/canlit161-162-ReadingFlick.pdf.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Harper Collins, 2007.