2] In this lesson I say that it should be clear that the discourse on nationalism is also about ethnicity and ideologies of “race.” If you trace the historical overview of nationalism in Canada in the CanLit guide, you will find many examples of state legislation and policies that excluded and discriminated against certain peoples based on ideas about racial inferiority and capacities to assimilate. – and in turn, state legislation and policies that worked to try to rectify early policies of exclusion and racial discrimination. As the guide points out, the nation is an imagined community, whereas the state is a “governed group of people.” For this blog assignment, I would like you to research and summarize one of the state or governing activities, such as The Royal Proclamation 1763, the Indian Act 1876, Immigration Act 1910, or the Multiculturalism Act 1989 – you choose the legislation or policy or commission you find most interesting. Write a blog about your findings and in your conclusion comment on whether or not your findings support Coleman’s argument about the project of white civility.

For this assignment, I have chosen to discuss the Indian Act 1876. I have chosen this act because I have briefly taken a look at it in one of my Gender and Women’s Studies classes in the past. I think that the Indian Act very much so is in agreement with Coleman’s theory of “white civility.” Also, much of the problems that the Indian Act has created (as we are talking about a constructed nation that is using this act to enforce an imagined idea of civility on a people) are still being felt today.

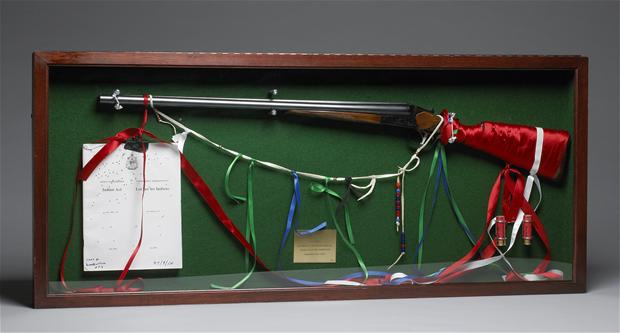

I remembered watching a video before on a bunch of really amazing art based on reactions towards the Indian Act 1876 that I wanted to post for you. Unfortunately, I was unable to find it, so I will be posting a picture of one of the more memorable pieces I have seen.

This is An Indian Shooting the Indian Act by Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun. If anyone is interesting in taking a look, there’s also 30 min documentary on him that can be found here. I haven’t had a chance to take a look yet, though, so I have no reviews for you!

In 1876, The Indian Act was created and enforced by the Canadian government in order to control and regulate Indigenous people and their land. While the Indian Act put many restrictions on Aboriginal life, there were a few key points that the Indian Act focused on. The Indian Act also created reserves in order to allocate land towards the government as opposed to the people that lived on those lands. The Indian Act changed existing structures that existed within Aboriginal society and replaced it with governmental structures in the form of band councils. Perhaps most important, The Indian Act was influential by creating the concept of Indian status, as well as who qualified for it. Indian status entitled those who held status to: ” treaty benefits, health benefits, the right to live on her reserve, the right to inherit her family property, and . . . the right to be buried on the reserve with her ancestors.” (Hanson)

The act is known for being extremely oppressive towards women in regards to status. Any woman marrying outside of her band was subject to, and often did, lose her status. This would often extend towards any children that were born through this marriage, taking both the woman and her children away from her culture and, often, into the imposed European culture that was being built into Canada. This could also occur if the woman were to marry another man of Indian status that was from another band. However, as Hanson notes, “if an Indian man married a non-status woman, he would keep all his rights.” So, it was quite clear that this document was formed with not just a racial bias, but with a gender bias as well.

While the Indian Act has gone through several revisions since it was first introduced, ” today it largely retains its original form.” (Hanson) On this wonderful page I found, Erin Hanson discusses why The Indian Act has not yet been abolished. Hanson says this is because “it acknowledges and affirms the unique historical and constitutional relationship Aboriginal peoples have with Canada.” So, while the Indian Act has been, and is, very destructive, to simply abolish it would be to get the Canadian government off the hook for everything that has resulted since the passing of the Indian Act.

In reference towards Coleman’s theory of white civility, I absolutely believe that the Indian Act was introduced as a means to impose the European conception of civility onto Indigenous culture. While the Canada we know today boasts of its multiculturalism, early attempts at nation building leave me to believe that Canada was not accepting of other cultures. So, rules and oppression were the tools that Canada used to mold what already existed in this nation into an image of civility that mirror white, European ideals. The Indian Act was not the only injustice that was imposed by the Canadian government on the Indigenous population and, though the government is attempting and continues to make amends, the wounds that it created in its mission of nation building will not easily be healed.

Works Cited

“Indian Act.” Justice Laws Website, http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/I-5/index.html. Accessed 28 Oct. 2016.

“Rockburn Presents – Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun.” YouTube, uploaded by cpac, 8 Aug. 2016, https://youtu.be/zEsU_GlJ53Q. Accessed 28 Oct. 2016.

Hanson, Erin. “The Indian Act.” Indigenous Foundations, http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/home/government-policy/the-indian-act.html#introduction. Accessed 28 Oct. 2016.

Yuxweluptun, Lawrence Paul. “An Indian Shooting the Indian Act.” May 2013, http://cdn.agilitycms.com/national-gallery/Images/Galleries/May2013/Yuxweluptun-An-Indian-Act-2012.0439.19A.jpg. Accessed 28 Oct. 2016.

Yuxweluptun, Lawrence Paul. “An Indian Shooting the Indian Act.” Tribe Inc., http://www.tribeinc.org/wp-content/uploads/tribe-Lawrence_Paul_Yuxweluptun.jpg. Accessed 28 Oct. 2016.