Wendy Red Star – Walks In the Dark – 2011

I had thought to begin this blog with a reflection of studying in #401F, and how that throughout the course I had come to realise how envisaging Indigenous Futurisms was integral to the act of studying Indigenous New Media itself.

It is true that in experiencing the pieces that we have this term, such as God’s Lake Narrows, Ashes on the Water and Isi-pîkiskwêwin-Ayapihkêsîsak , we have been paying homage and looking at artists and creators invested in making pieces that speak to mediums of futurism. However, I think to simply approach things from this way eclipses the fact that Indigenous Futurism is an act not tied to an academy or an intellectual ideal, but I think perhaps more powerfully a reality for Indigenous people across the globe.

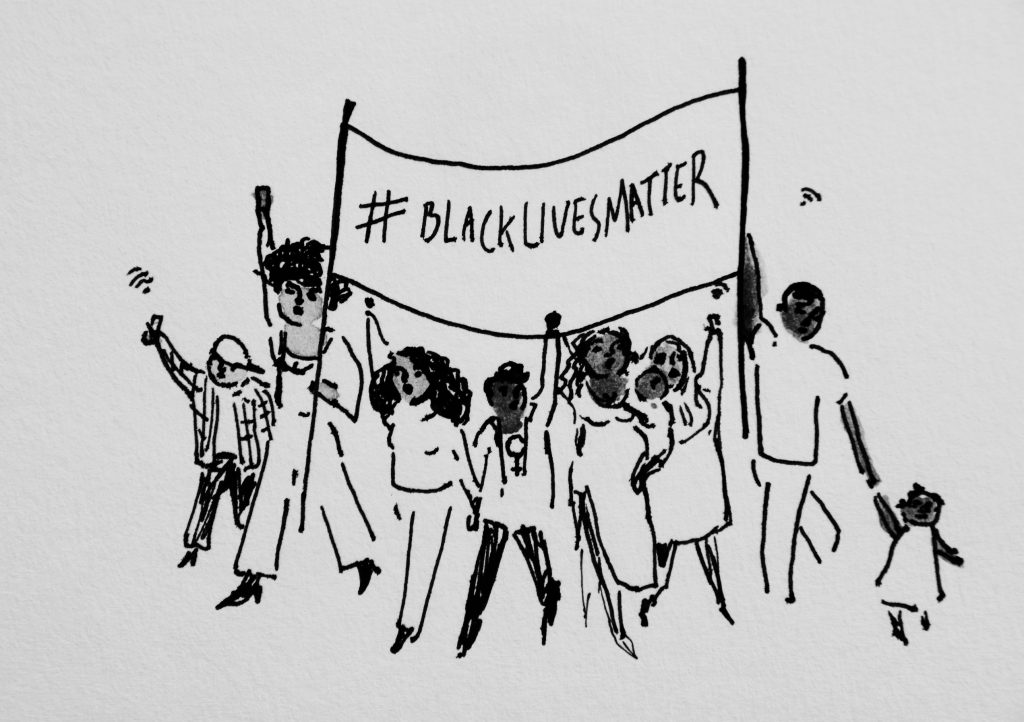

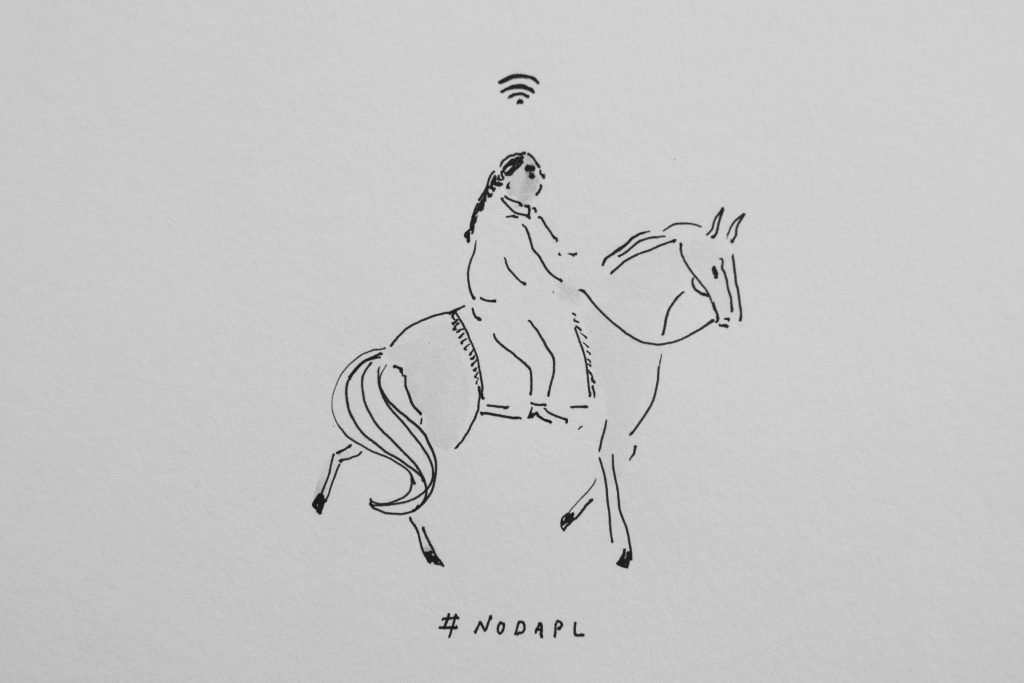

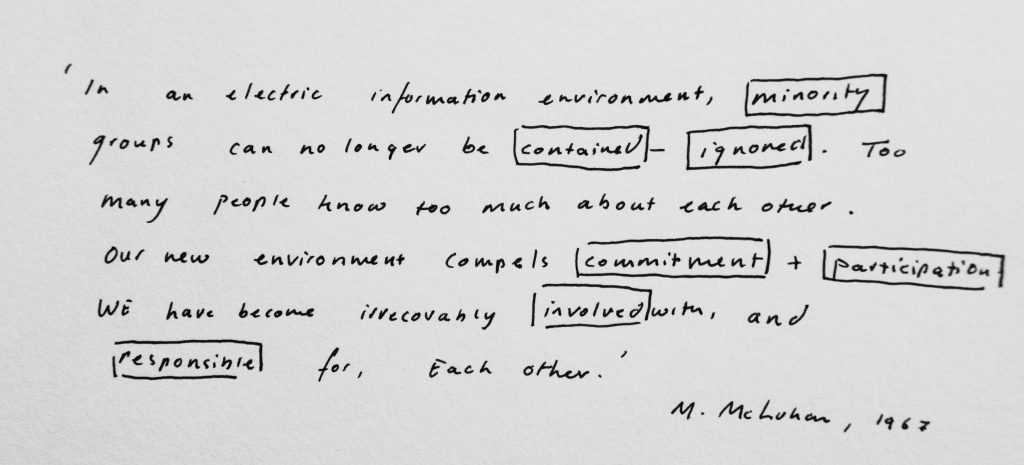

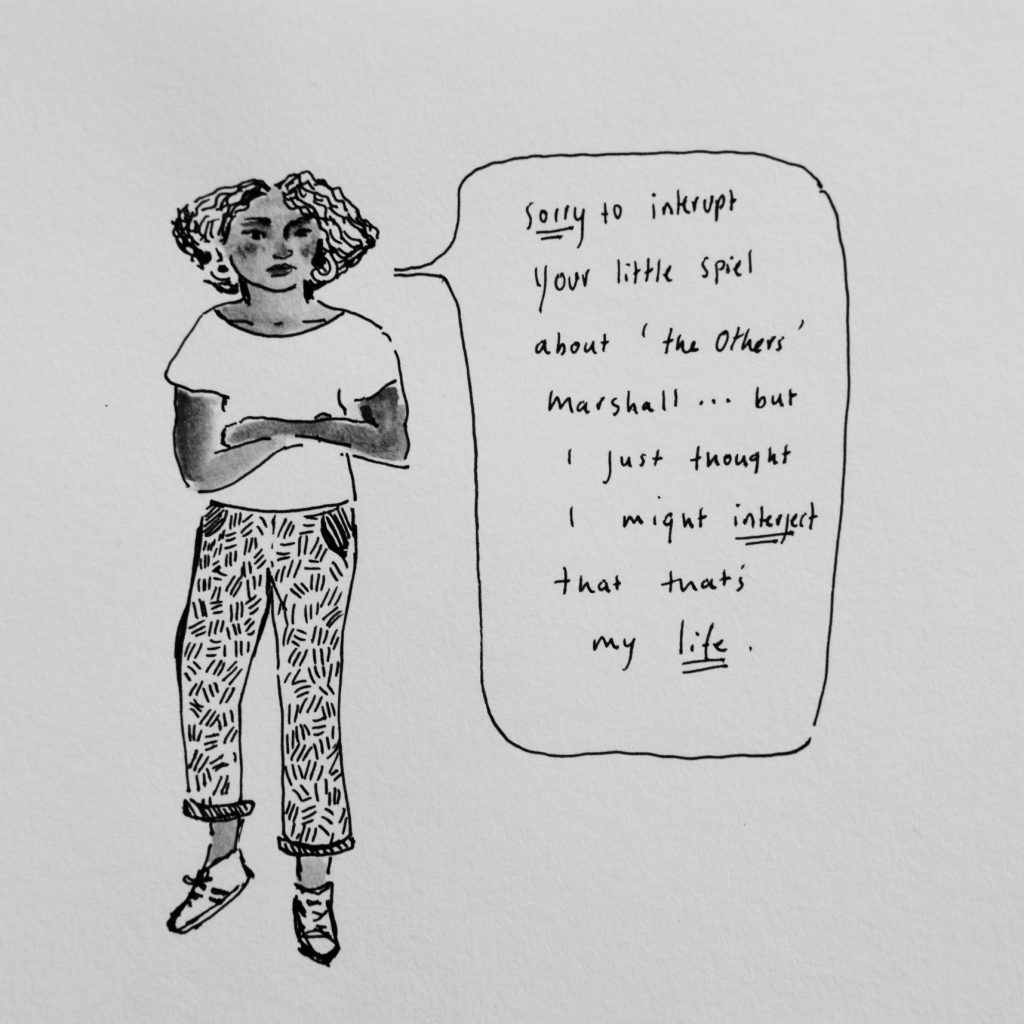

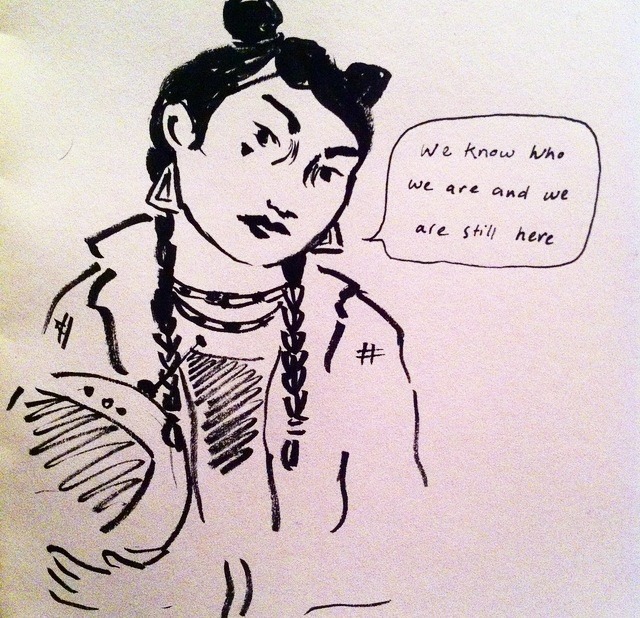

We only have to look down to North Dakota now to see what the lived reality of living in a colonial society for Indigenous people often looks like. That is, to live in a society that systematically wants to erase and decimate Indigenous bodies and the inherited and unquestionable sovereignties that they represent. Because of this, I see Indigenous futurisms as less of an academic idea, or even a concept arising from a rejection of Western Science Fiction tropes (Cornum, online), but rather as an everyday act of existence and resistance. Indigenous futurisms is not just saying We Are Still Here, it is saying -We Will Always Be Here.

When I think of what is at the core of Indigenous Futurisms I think I envisage less of a Wendy Red Star imagining, but rather a concept more deeply tied to praxis rather than theory, in Viewing Timetravller TM and Reading Leanne Simpson’s Land as Pedagogy, three main points stuck out to me in regards to Indigenous Futurisms:

~ The act of imagining a future as being integral to survival

~ The act of imaging a future as being intimately connected to past

~ Centralising Indigenous experiences and knowledges in a future world

Taking this as the starting point, then I think the possibilities of what Indigenous Futurisms could look like is infinite. Two examples that I came across when researching this blog and that really inspired me were Lou Catherine Cornum’s The Space NDN’s Star Map, and Wendy Red Star’s Thunder Up Above ( I named one of my character’s after her as she is so bad-ass!)

….

Timetravller TM treatment.

to start with: a personal note on Second Life….

So I did it, I tried it, I tried second life…

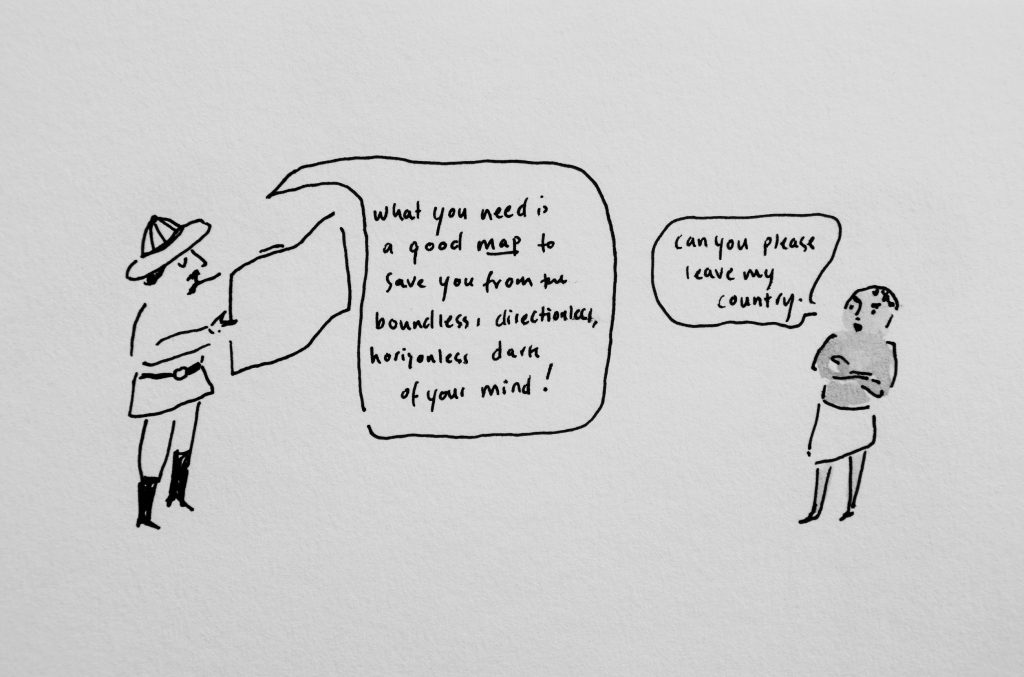

I got there, got gender-conforming avatar, proceeded to take off all its clothes (how?) and it’s hair (how!?) and get it stuck half in and half out of a wall (I don’t even know). If the medium is the message, then I think I can say with a great deal of confidence that I am not interested in that message. As someone who spends a fair amount of time creating things, I find it exceedingly frustrating to be have to create something only within the bounds of someone else’s creative rules. Please know that I tried this and gave it a fair go, but I was just physically unable to try and represent what I wanted to, which was pretty sad when trying to be creative and / or imaginative. Which is why very soon after my computer gave me the spinning wheel of death (technologies equivalent to giving the finger) I cut my losses and put it in the trash.

What actually is First Life though?

Act one: Karahkwenhawi and Hunter are expecting the birth of their first child, the two young parents to be are filled with joy at the thought of bringing this new life into the world. They have discovered that the glytching pair of glasses is also able to carry their wearer into the future, they decide to visit earth seven generations forward into the future in the tradition of trying to envisage a world seven generations forward / seven generations back.

The year is 2300, the Earth, so long trying to keep her children alive has caved to human greed and desire. She is now is a shell, a brittle labyrinth of dust and tunnels from which every last scrap of recourse has been extracted. The only thing that moves amongst the rubble of what was our Earth are huge robotic like structures, born our of the detritus and junk of hundreds of centuries of objects made for destruction. These metal beings roam the earth, slowly smashing up what is left of the earth that was once known to us. Amongst them roam the unSettlers, hungry ghosts with nothing left to consume or eat… these pale creatures neither speak nor communicate in any way that people can understand, it is said that once they were human, but hundreds of years of greed and desire has cursed them, left them hollow and ghost-like – never filled but always wanting more. They drift across the Earth’s hollow surface, clustering in groups, and staring with their pale sightless eyes. The humans who have survived have moved into space – living on space stations and ships designed and created from salvaged technologies from the broken Earth.

Act two: Karahkwenhawi are devastated at the state of the world that her future generations will inherit – suddenly out of the blue one of the metal beings appears and begins to smash up the area around Karahkwenhawi and Hunter, fleeing from danger they are picked up by a mysterious figure on a small space jet.

Act three: Taken back to the space Station, Karahkwenhawi and Hunter learn that their saviour is a fellow Mohawk, Wendy – who has not only saved them from danger – but created a whole space station that has recreated a beautiful earth-like environment.

She explains to them that the Mohawk people are still practicing sovereignty within space, and although they are now dislocated by one more step from their homelands, the strong worldviews and ontologies that have held hundreds of generations in survival are still powerful and alive. “Since our territories were first invaded, we have been constantly moved and removed from our homelands, this hasn’t made and never will make our sense of identity and knowledge of place any weaker… we know who we are are and we are still here.”

Act Four. Wendy shows Karahkwenhawi and Hunter the way the people at the station are preserving and protecting their animal and plant brothers and sisters and shows them her plan to begin reconstructing the ecologies and human/non-human kinship networks of earth using the use of technology created from salvaged materials, and the wisdom passed down to her from her ancestors.

As it is time for them to leave, Karahkwenhawi notices Wendy wearing a thin necklace around her throat which she recognises as one she has beaded herself. When she asks Wendy about it Wendy explains that it is a very important necklace to her, which has been passed down to her by her grandmother… Karahkwenhawi smiles quietly to herself, knowing that the future for her child will be bright.

….

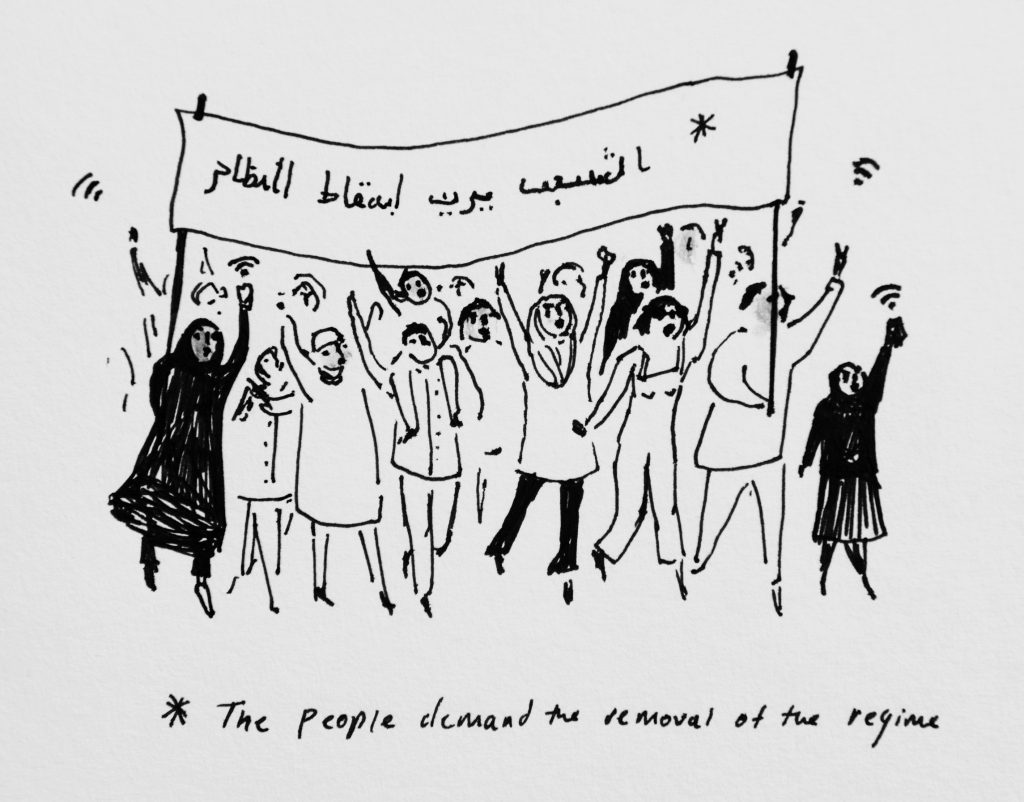

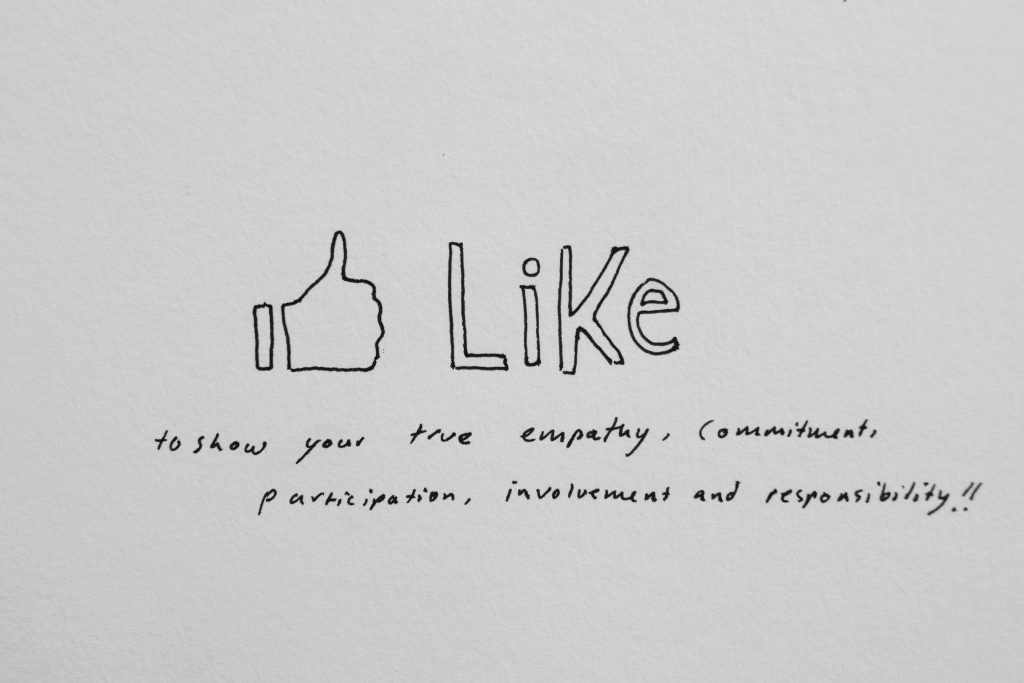

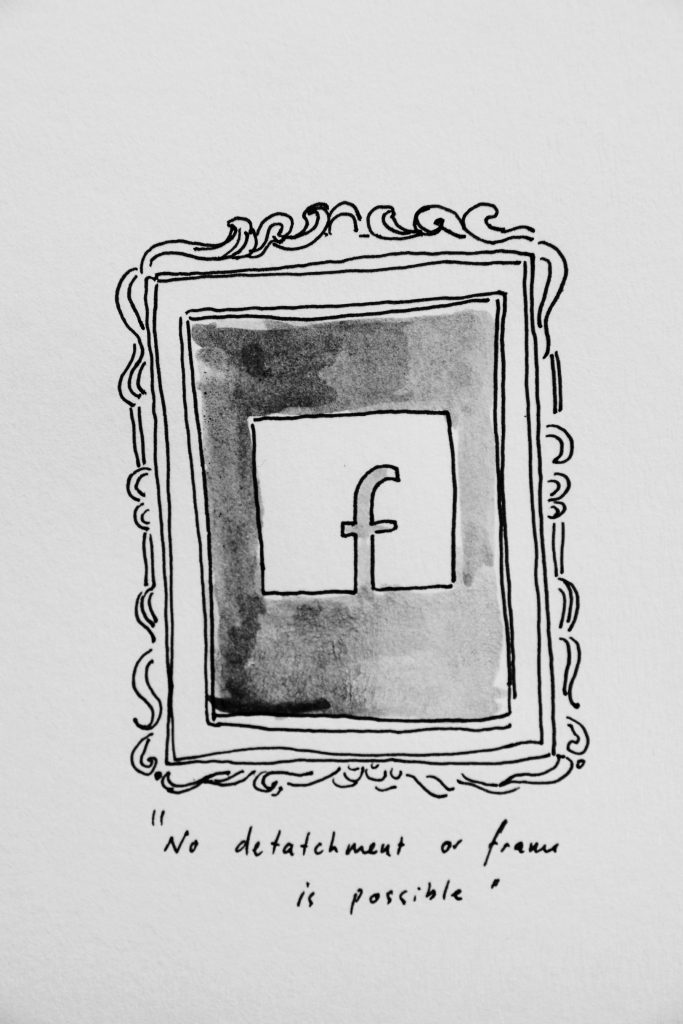

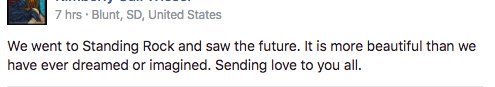

Just on a beautiful closing note. When researching this blog, I found a Facebook page dedicated to Indigenous Futurisms. As I opened it up I read the top post, which had only been written a few hours before… It made me think (again) about what is happening down in North Dakota, but this time – rather than the struggle being eclipsed and defined by the violence that is happening to the water protectors down there, it was clear what was at the core of the #NoDPAL struggle. It read:

(https://www.facebook.com/groups/349927541693986/permalink/1305479762805421/)

…

References:

Lou Catherine Cornum – The Space NDN’s Star Map, 2015, (online).

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson “Land as Pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation”, Decolonisation: Indignity, Education and Society, 3:3, 2014

Skawennati, Timetraveller TM, http://www.timetravellertm.com/

With Gratitude to Wendy Red Star http://www.wendyredstar.com/