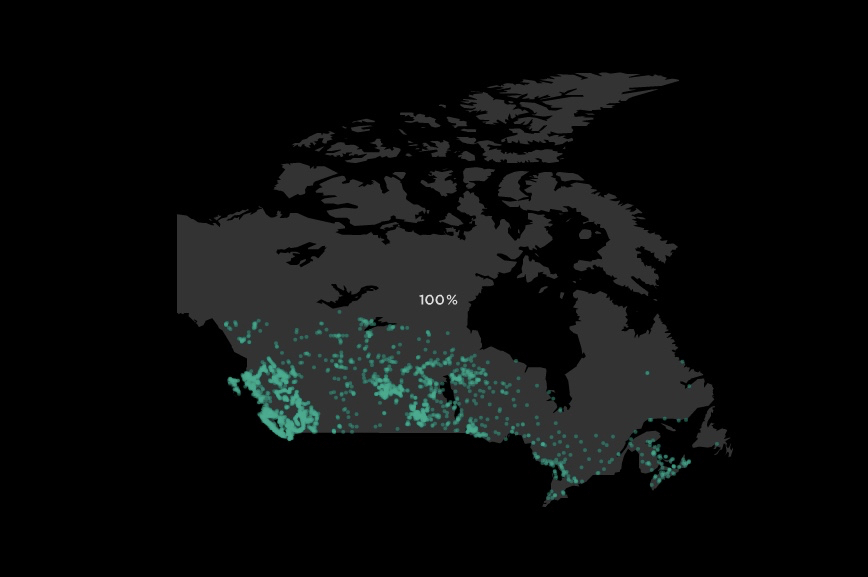

I watch as the screen begins to load, the familiar percentage mark rising quickly from zero to one-hundred, positioning me in the safety of the media world. I know the rules here, I know this “territory”. Behind the rising numbers the shape of Canada appears, across the country dots begin to blossom, spreading out across the land at the same rate of the rising numbers – this is different, this is unusual. I look for my temporary “home”, this strange place where I am staying, where I feel connected to, yet where I feel disconnected from: alien, visitor, coloniser – “Vancouver – Beautiful British Columbia”. The dots rise and rise, marking out the land with the positions of the reservations, marking out the spread of colonisation as it marched its way North, until the cold and “wilderness” stopped its progress (or the legal definition of “Indian” divided policy on Indigenous bodies between the south and the north). Then till now, zero till one-hundred percent… The map of Canada holds for a second, allocated spaces glistening green and glowing: this map doesn’t simply tell the locations of reserves, but the movement of legalised control of land by the coloniser – yet at the same time it still resists this. Watching the map glimmering green on the black background I think “this is all 100% Aboriginal land”.

In her article “Vancouver’s Aboriginal Media World” in Sovereign Screens: Aboriginal Media on the Canadian West Coast, Kristen Dowell defines Aboriginal screen sovereignty as “speaking back to the legacy of misrepresentation in dominant media is the act of cultural autonomy that reclaims the screen to tell Aboriginal Stories from Aboriginal perspectives” (Dowell, 2013, 2). She locates this, not simply through the engagement with Indigenous content or issues, but through the act of production itself, situating the repossession of media space (used so long as a colonising tool in the national myth-making agenda of colonising nations) as an act that transcends the final media result, but is enacted through the physical and conceptual journey of production.

Kevin Lee Burton’s piece “God’s Lake Narrows” speaks directly back to that history of visual and media colonisation of Indigenous bodies, stories and spaces. Burton inverts the idea of the Indian Reservation as depicted in the media by explaining his own relationship to his reserve at Gods’ Lake Narrows. Throughout this piece, Burton again and again disrupts the narrative of what a reserve or reserve life is seen to be by an outside audience, he points out that “… the closest reserve to Vancouver is 3.8 km. If you’re not an Indian, you’ve probably never been there” (Burton, 2011). From the very beginning Burton opens up and problematises the stereotypes associated with reserves and the people that call them home.

Burton moves his viewer from the map and his opening challenge that most (non-Indigenous) viewers have little or no understanding or lived experience of a reserve, into his exploration of the “reserve aesthetic” (Burton, 2011). Here Burton intersperses images of reserve houses with written words, disrupting the “view” of a reserve that a non-Indigenous visitor may have passing through by car, or glimpsed on the news. The reserve aesthetic is a language, if you can’t read it, you won’t understand it, Burton argues “if you’re from a reserve, houses can tell you certain things. You know this person sacrificed his income for his Four-Wheeler and you know why his porch door is worn and torn. If you’re not from a reserve all the houses may look the same to you” (Burton 2011). By showing the images of the outsides of the reservation houses, Burton re-appropriates the symbols used on countless news reports and newspaper articles, and problematises the single story of “poverty” that they have come to represent.

This idea is driven home (quite literally) in the second part of God’s Lake Narrows where the space of the piece moves from the outside of the houses to the interior. Suddenly the soundscape changes, no longer is it the crunching of snow or the crackling of the two-way radio (a soundscape that has already begun to disrupt the depiction of reservation houses as static or silent) and into a softer warmer place. With the guitar in the background the viewer moves through the interiors of the houses. There is nothing voyeuristic about this. Burton forces the viewer to be confronted by the houses inhabitants, who gaze steadily back at the viewer, resisting being read only as passive objects caught by the camera. Suddenly, by seeing the houses interiors and the people who call them home, the viewer is forced to look beyond the facade of the “reservation aesthetic” and into these spaces as places of family, connection and ultimately home.

I spend a lot of time staring at the picture of the young mother holding her child. I know that look, that fierce, brave, terrified young mother look – I have seen it countless times on my own sister’s face… I look at stick-and-poke tattoos on her arm in Cree, her partner playing guitar in the background. I have only been in Canada for a couple of months, and have never set foot in a reserve house but I know that scene so well – it could be something out of my own life back at home in Australia. And yet, all of these pictures resist captioning, Burton gives the viewer no explanation and no possibility of knowing his relationship to the people in the photographs, or even who they are.

Looking though these I am confronted by my own privilege that underpins my right to “know”. Who is this mother, what is her name? I’m not given anything except the image, the unflinching gaze of the sitter and I am deserving of nothing more. Burton again disrupts the unearned privilege that the coloniser who feel entitled to knowledge or understanding in relation to Indigenous peoples and stories. Looking through these images I can’t help but think of a National Geographic magazine that I found once, which also had a big expose on the Pine Ridge Reservation in Dakota. I think about those images, beautiful yes, but images that tell one particular story. The photographer’s name was Aaron Huey, and although there is no doubt that telling and showing the stories of the Lakota Sioux has become his life passion, I wonder what the politics are of a white guy (even a white-guy aware of his privilege) capturing these stories and sharing them on a platform like National Geographic (perhaps North-America’s biggest manifestation of the Western Right to Know).

This right to know and entitlement to knowledge ties in directly with one of Dowell’s concepts in her article. Dowell argues that all Indigenous media production comes first and for most from community and for community, “When and Aboriginal director is behind the camera, his or her tribal community and an Aboriginal audience are often configured as the primary audience” (Dowell, 3). In this way, Burton has created a piece that, although resits unearned “knowledge” or “understanding” for a non-Indigenous audience, will have a very different reading for someone who has grown up on a reserve or for someone associated with God’s Lake Narrows itself, for whom the the sitters in the portraits may be neighbours, friends or family.

By creating a piece like God’s Lake Narrows, Burton has inverted the settler right to know, but also, and more importantly asserted his own right to screen sovereignty, taking back Indigenous images, stories and depictions into his own hands and the hands of his own community as a way of speaking back to the legacy of colonisation that goes hand in hand with media production. Through the outside / inside binary Burton subverts stereotypes associated with Indigenous lives and presents a new depiction of Indigenous realities both about, and for his own community.

Dowell, Kristen “Vancouver’s Aboriginal Media World”. Aboriginal Media on the Canadian West Coast. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2013. 1 – 20.

Burton, Kevin Lee “God’s Lake Narrows” http://godslake.nfb.ca/#/godslake

Beautifully written introduction, Iona and I love your analysis of Burton;s loading screen. I think you could extend the ideas there into a piece unto itself–particularly how this piece speaks to you as an international student. Great work!

There is a lot of ‘disruption’ happening in God’s Lake Narrows and I appreciate that you’ve pointed out that the text disrupts the stereotypical view of the reserve. I talk about this a bit in my blog post as well but I enjoy how you’ve phrased it here. Your reflection on colonial entitlement to knowledge is also very interesting to me as I reflected on that a fair bit throughout watching God’s Lake Narrows and writing on it.

A lingering question that the piece and your blog raise for me is how do we as settlers approach knowledge and learning in a decolonial way? A couple years ago I speaking with Thomas King after he was awarded the Charles Taylor Prize for Literature and he said that one of the best things that non-Indigenous allies can do without appropriating the Indigenous struggle is to stay informed about the current issues going on around them that are important to Indigenous people. I’m wondering if you, or anyone else, knows how we can do this while at the same time rejecting ‘colonial ways of knowing’ and entitlement to knowledge. Great Post!

Hey Clara,

Yes this is a really important question, and one that I have reflected a lot on as a settler student studying in First Nations Studies.

I think that Thomas King is absolutely spot on in pointing out the importance of staying informed around current issues, and further to this, I would say being aware about larger discourses of racism, policy and discrimination of any form in our everyday lives – being critical of the ways that power plays out in the world around us, and not confine our learning to a classroom space.

I think it is also important to recognise where it isn’t your place to “know” and accepting that not-knowing. This doesn’t mean not engaging, but I think, always questioning why we want to know, and questioning if it is our space to know – and maybe in some cases, finding different ways of engaging with that issue.

Thank you for your question! I don’t by any means feel like I have a “right” answer, but I do think that it is really important to think and be questioning as we move through this learning.