Every time I enter the Museum of Anthropology (MOA), I feel hopeful that this time it will be different. I feel good, at first, in the minimalist space, enveloped by concrete, natural light, and high ceilings. Tucked between cedars, on the edge of a cliff that overlooks the windy Pacific, MOA is located on a powerful, spiritual piece of land. But it doesn’t take long before the bitterness and resentment start to wash over me. I see and hear that MOA is trying. Artworks by Musqueam artists stand at the entrance, evidence that a more positive relationship is being forged between the institution and the Indigenous peoples on whose traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory the institution stands. But as soon as I enter through the doors, and I feel the spirits of the totems standing there, so far from home, I start to feel sick. Uprooted. That is the word that came to me on my first visit, and it is the word that still haunts me. I come upon my partner’s family house post, and I speak to my great-grandfather-in-law. Meegwich moshum. Thank-you for standing here. You are loved. You are missed. You are remembered. By the time I enter the multiversity gallery I can’t keep the disdain off my face. I remind myself that MOA is doing some great work to create space for relationship building. Native youth give tours. Some of the display cases are curated in partnership with First Nations. But the walls and the drawers are so crammed full of items, I wonder how the spirits have room to breathe. To move. To dance. There are so many masks, drums, carvings, baskets, and tools it is as if I have entered an ethnographic hoarding situation. Why are these here? How did they get here? Who do these belong to? I am not the first person to ask these questions. They are questions folks who tour the museum, who write about the museum, and who work at the museum constantly ask.

Moving on, the tour starts to get more personal. I come upon the small section devoted to the Plains. My people. A relative’s moccasins. A relative’s headdress. A relative’s basket. I look closely at the glass display cases. If I am entirely honest, my agitation is coupled with a bit of desperation. I am looking for medicines, looking for signs of my relatives. It is part of my search to recover my own Nahkawe-Nehiyaw identity, something that was also seized temporarily by colonization. I am looking for something that might help quell the ancestral grief that lives in my bones, if just for today. I put my hand on the cool copper handle of the drawer beneath the glass case. I have heard these drawers are special. Imported from Europe. Very expensive, you know. The drawer slides open gracefully. I almost cry out when I see what is inside. Sacred pipes. I am told that Pipes were given to the world to help to heal the people. Pipes are meant to smoked, to carry our prayers to Gihzwe Manido. Pipes are meant to be in ceremony. Pipes are meant to be lovingly carried in beaded buckskin, and feasted. And here they are, sitting in a bourgeois anthropological museum, objects of curiosity.

——-

It has been over a month since I saw the pipes at the MOA, and I am still thinking about them. I see how much healing my Indigenous communities, friends, and family need, and I know those pipes can help to do that work. It is hard for me to know that they are in there, unable to carry out their original instructions. I could hear the pipes singing songs of sadness, loneliness…their spirits are hungry for love.

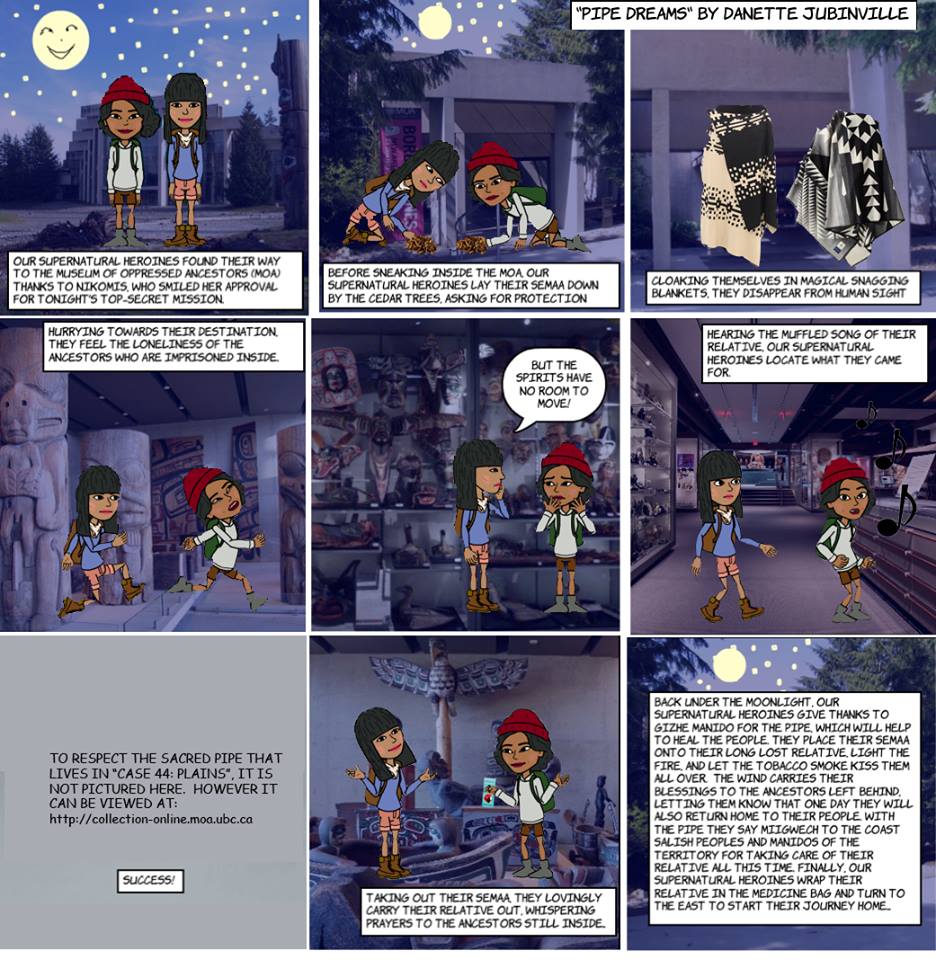

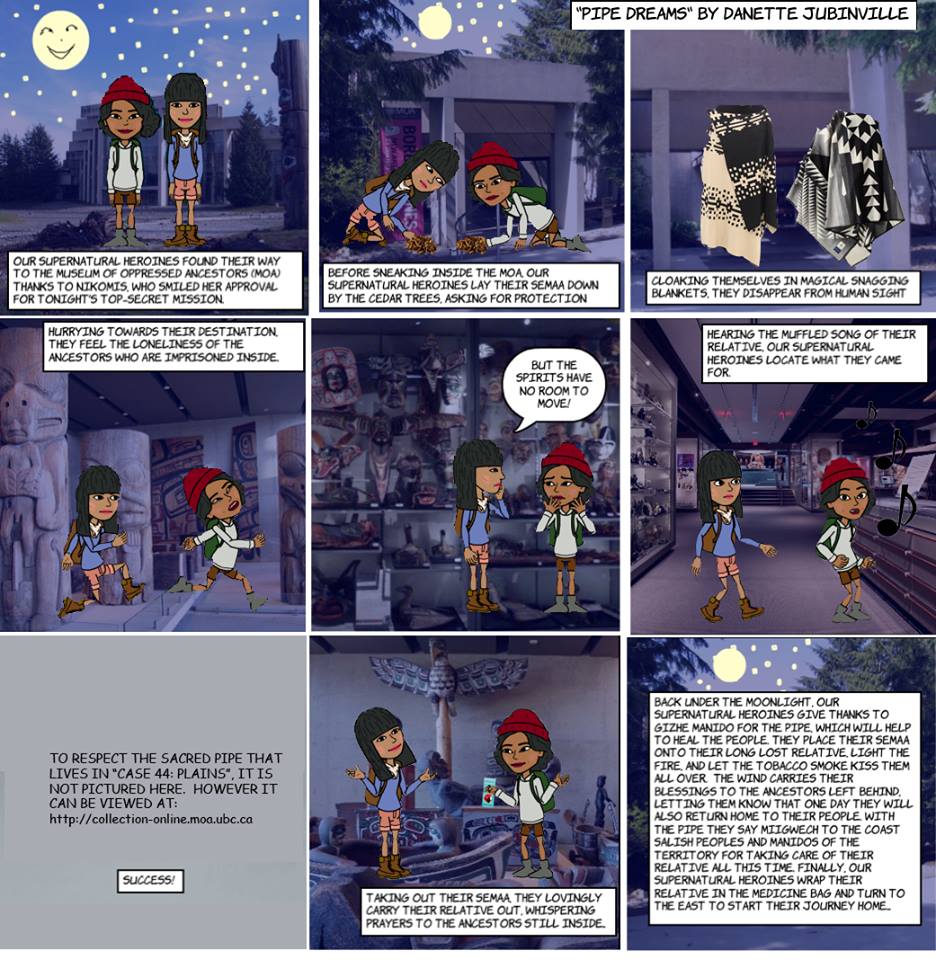

Following my encounter with the pipes at MOA, I felt inspired to respond. I drew a comic strip, titled “pipe dreams”, which allowed me to explore new possibilities through imagination and fantasy. While pipe dreams is clearly a critique of museums, and MOA in particular, it is not meant to discount the good work that is being done in those institutions. The Museum of Anthropology is a world leader for its progressive policy reform and extensive efforts to work collaboratively with Indigenous peoples, thanks to Indigenous activism and visionary work done by museum staff. Community outcry to past displays of sacred ceremonial objects has resulted in teachable moments for both the institutions and the public. Today, an empty display case in the Multiversity Gallery makes a statement that educates visitors on respect for cultural protocol. Evidence of the institution’s humility, many exhibits at MOA provoke interrogation of museum practices. And perhaps the most encouraging aspect of MOA is that it has demonstrated a commitment to working with the Indigenous community. In these ways, MOA has shown that museums can simultaneously be sites of colonization and decolonization.

And yet, I cannot ignore the way I felt in my body and spirit during my last visit. Sometimes I wonder, why do museums have to exist, as a given? I see the value in galleries displaying objects, art, and artifact with permission of those who made them (or their descendants). But for those items that were stolen or otherwise dishonourably acquired, for the items that are shown with question marks on their identification cards…do those items have to be kept? It cannot be ignored that MOA is a multi-million dollar facility that draws in tourists. What message is being sent to those who do not have the tools to think so critically, or those who are not so familiar with the nuanced histories and context of MOA and its collection? While those questions are important, the questions that are really on my mind, and that I mean to pose with pipe dreams, are this: What are our responsibilities, as Indigenous peoples, to objects that were given to use to care for by our ancestors, but are now locked behind glass? And, knowing that they may or may not eventually return to our communities, how can we feed their spirits?

Danette Jubinville, 3rd Year FNSP Major, Saulteaux, Cree, French, German, Jewish, Scottish & English ancestry

Follow

Follow