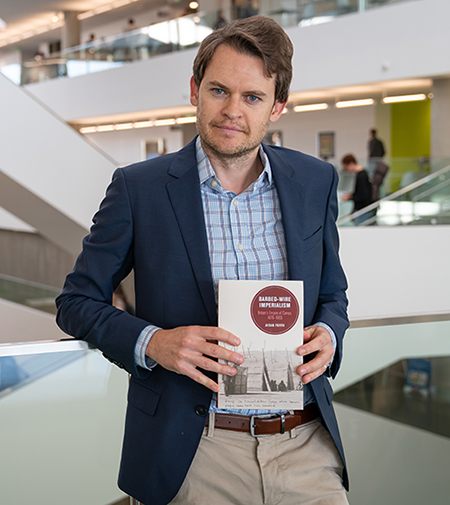

Justin Richard Dubé est candidat à la maîtrise en histoire à l’Université du Québec à Rimouski. Ses travaux s’intéressent principalement à l’histoire politique et intellectuelle canadienne et québécoise des XIXe-XXe siècles. Entre autres, il a publié un compte rendu de l’ouvrage de Carl Brisson et Camil Girard, Reconnaissance et exclusion des peuples autochtones au Québec, dans la revue Histoire sociale/Social History (2019). Il signe également un article sur l’annexionnisme au Canada français dans le Bulletin d’histoire politique (2021). Vous pouvez lire son article,“L’octroi du droit de vote universel autochtone aux élections fédérales” dans JCHA/RSHC 31 no.2.

Qu’est-ce qui vous a amené à vous intéresser à l’histoire politique du Canada des XIXe et XXe siècles?

C’est un intérêt qui remonte à ma toute première session au baccalauréat en histoire, et même avant. Je ne pourrais dire quelles motivations précises m’ont engagé dans cette voie disciplinaire : le cœur a ses raisons que la raison ignore ! Je me souviens d’avoir été intrigué très tôt par des personnages tels que lord Durham et John A. Macdonald. Ce sont deux hommes pour lesquels je n’ai pas personnellement la plus grande sympathie, mais c’est paradoxalement ce qui a dû stimuler ma curiosité. Depuis lors, le rapport des autorités fédérales envers les minorités nationales canadiennes n’a cessé de me fasciner. C’est sans doute un lieu commun, mais on comprend tellement mieux le cadre politique actuel, la dynamique des partis, ou encore l’évolution des idéologies lorsque l’on prend le temps d’analyser en profondeur les individus, les concepts et les évènements qui les ont forgés.

Comment en êtes-vous venu à étudier les débats parlementaires de 1960?

En fréquentant l’historiographie politique canadienne, j’ai été plutôt surpris par la quasi-absence d’informations sur l’accès des Autochtones au droit de vote. Par contraste, en histoire des femmes, on a accordé une place considérable aux luttes suffragettes. Au Québec, tout le monde sait que le droit de vote a été définitivement concédé aux femmes en 1940. Mais qu’en est-il des Autochtones ? Je n’en avais aucune idée, et j’ai vite constaté que je n’étais pas le seul. À l’approche du 60e anniversaire de l’octroi du droit de vote fédéral à l’ensemble des Autochtones (1960-2020), j’ai donc choisi de prendre le taureau par les cornes et d’aller moi-même jeter un coup d’œil. J’avais constaté que l’historiographie avait totalement négligé les débats de 1960, ce qui me semblait assez problématique. Les échanges parlementaires me semblaient donc la première source à aller consulter, afin d’analyser la séquence évènementielle et les motivations des députés. L’octroi du droit de vote reste d’abord et avant tout un acte législatif, et devait être étudié comme tel.

Comment les députés ont-ils concilié le passage du refus du droit de vote aux autochtones sous le gouvernement précédent à un soutien sans réserve sous Diefenbaker?

Je n’ai pas de réponse définitive à cette question ! Je peux cependant lancer quelques pistes de réflexion. D’abord, il apparaît clairement que l’initiative est venue du gouvernement de Diefenbaker, et non des députés en tant que tels. Autrement dit, le point de bascule a d’abord été l’élection des progressistes-conservateurs à la fin des années 1950. Je doute que les députés conservateurs aient tous appuyé sans réserve le droit de vote autochtone, s’il n’y avait pas eu cette impulsion de la part du chef du parti. Notons que les conservateurs avaient manifesté à plusieurs reprises leur sympathie envers le droit de suffrage dans les années 1950, tout comme les sociaux-démocrates (CCF). Le principal obstacle sur leur route demeurait le gouvernement du Parti libéral de Louis Saint-Laurent. Renvoyés dans l’opposition, les libéraux se sont retrouvés sur la défensive. Le changement d’attitude auquel vous faites référence a d’abord été celui du Parti libéral. Certains libéraux avaient été favorables au droit de vote autochtone depuis longtemps, mais la majorité d’entre eux avaient suivi la ligne de conduite du cabinet de Saint-Laurent. Ce sont eux qui furent amenés à justifier leur revirement idéologique. La conciliation fut très difficile. Par exemple, les contorsions discursives de l’ancien surintendant aux Affaires indiennes Jack Pickersgill pour justifier sa volte-face n’ont pas paru très convaincantes aux yeux des autres députés. Il faut rappeler que le nouveau chef du Parti libéral, Lester B. Pearson, était très préoccupé par la réputation internationale du Canada. Il se révéla ainsi fort vulnérable aux arguments de Diefenbaker, qui voulait explicitement protéger cette réputation en maximisant l’égalité des droits. À partir de là, la plupart des libéraux n’ont pas eu le choix d’ajuster leur discours et leur position en fonction des nouvelles sensibilités de leur parti, et du contexte idéologique en général.

Quel a été l’héritage des débats parlementaires de 1960 au-delà de l’émancipation?

Il s’agit d’abord d’un héritage idéologique. Personne n’a remis en question le droit de vote autochtone depuis cette époque. Quiconque viendrait le contester serait assurément et unanimement condamné sur la place publique. Dans les faits, l’universalité du droit de vote en général a été grandement renforcée par cette réforme. Il n’apparaît plus du tout acceptable aujourd’hui qu’un segment de la population soit privé du droit de suffrage pour des motifs culturels, économiques ou autre. L’arrimage entre la citoyenneté, le territoire et les libertés publiques s’en est trouvé renforcé, et surtout, devenu incontestable. Les débats de 1960 constituent alors un jalon important dans l’avènement de cette une nouvelle norme sociale, idéologique et politique.

J’ai tendance à croire qu’ils nous ont aussi laissé en héritage deux autres éléments. Premièrement, en refusant de créer des circonscriptions protégées sur le modèle néo-zélandais, les politiciens fédéraux ont clairement statué que le caractère national distinct des communautés autochtones n’avait pas de conséquence sur leur mode de représentation à la Chambre des Communes. Rappelons que plus tard, l’échec de l’accord de Charlottetown empêcha que soient consacrés au minimum 25% des sièges au Québec en raison de son identité historique et culturelle. À la lumière des débats de 1960, on comprend que le rejet d’une conception plurinationale de la répartition des sièges et la prépondérance d’une vision uniformisatrice s’inscrit dans le temps long. Secondement, en se faisant les porte-paroles autoproclamés des communautés autochtones résidant dans leurs comtés respectifs, plusieurs députés ont pu contribuer à pérenniser l’instrumentalisation idéologique de l’autochtonie à des fins politiques ou morales, en plus d’essentialiser et d’homogénéiser leurs positions.

En repensant à cet article, y a-t-il quelque chose que vous aimeriez y ajouter ? Fait-il désormais partie d’un projet ou d’une série plus vaste ? Avez-vous découvert de nouvelles informations qui modifieraient ou amélioreraient les recherches que vous avez précédemment effectuées?

J’aurais beaucoup aimé avoir le temps d’analyser en profondeur les réactions de la presse locale et internationale. Pareillement, j’aurais sans doute été comblé de pouvoir conduire la même enquête du côté américain, australien ou néo-zélandais, pour pouvoir tisser des liens entre les expériences de ces différents pays. L’analyse des débats des années 1950 serait également fascinante à effectuer, pour justement mieux voir l’évolution entre le refus obstiné de la Chambre et son revirement soudain en 1960 en faveur du droit de vote. Enfin, je crois que j’aurais pu davantage parler du rôle de Lester B. Pearson et de la transformation du Parti libéral qu’il a opérée à partir de 1958. Cependant, ces bonifications auraient nécessité des recherches supplémentaires, et auraient donc retardé la parution de l’article, que je tenais à publier dans un délai d’au plus deux ans après le 60e anniversaire de la réforme. Étant présentement occupé par d’autres objets d’étude, je ne prévois pas transformer cette recherche en un projet plus vaste pour les prochaines années. J’espère toutefois que d’autres historiens sauteront sur l’occasion pour pousser la réflexion plus loin, le champ est libre !

Avez-vous lu quelque chose de bon récemment?

Je suis en train de lire The Righteous Mind, de Jonathan Haidt, un remarquable essai de psychologie morale, très accessible pour les néophytes. Il aborde des éléments aussi captivants que le rôle des émotions dans le raisonnement moral et les origines évolutives de l’éthique. Tous les historiens, me semblent-ils, gagneraient à creuser ces questions fondamentales à la compréhension de l’être humain. Je traîne aussi sur ma table de chevet les Pensées de Blaise Pascal, un grand classique de la philosophie et de la théologie chrétienne.

Dans un registre plus ludique, je me suis plongé récemment dans la série Dune de Frank Herbert. Que vous ayez vu ou non le film de Denis Villeneuve, allez visiter l’œuvre : les amateurs de science-fiction adoreront !