1] Explain why the notion that cultures can be distinguished as either “oral culture” or “written culture” (19) is a mistaken understanding as to how culture works, according to Chamberlin and your reading of Courtney MacNeil’s article “Orality.

According to Jeremy Norman, the first time in recorded history where orality was translated to literacy was in ancient Greece. At the time, its purpose was to take information passed down generations orally and preserve it to prevent it from being lost in translation — or, in this case, lost in oration. While Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt had produced some of the earliest documents, “there is little or no documentation of the [actual] transitions from oral to written culture in those regions” (Norman). This arbitrary separation between “oral culture” and “written culture” has been engrained in European culture for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. The reverence held towards literacy has been found everywhere from the monks in the church to the scholars and philosophers of the Renaissance. The irony being, of course, that literacy was not for the masses until the dawn of the Gutenburg printing press, where the Bible was accessible in multiple languages and available for the masses. Before the Gutenberg, literacy in Europe was available only to church officials, monks, and nobility. With this in mind, of course the majority of Europe was still an oral culture; yet, there was this precedence of literacy and, today, there is a general assumption that Europe has always been a culture of literacy and not orality.

I believe this assumption of European literacy is the catalyst for the divide between “oral culture” and “literal culture”. In European/Western tradition, literacy is upheld and viewed as the utmost of importance insofar that if you are illiterate, you will not have many opportunities to succeed in life. However, Western tradition overlooks the fact that we are still an oral culture. While writing mediums such as letter writing, e-mail, and text messaging are available to communicate with others, much of our day-to-day is spent in oral communication. Regardless, many Western academic attitudes consider orality to be a lesser form of communication than literacy. Orality is “the marker of “tribal man … [and] … a primitive or undeveloped medium” (MacNeil), and Western tradition prides itself in being anything but primitive.

This condescending attitude towards orality is both incorrect and hypocritical. Firstly, as MacNeil points out, a majority of the world is still part of the “oral culture”. To call orality primitive and undeveloped when it is a major form of expression in the world is both narrow-minded and Eurocentric. Globally speaking, I believe the only place where literacy is more common than orality is over the Internet. Even so, YouTube – a multibillion dollar company owned by the American conglomerate of Google – is hugely successful and almost entirely an oral culture of story telling. Yet orality is “tribal” and “undeveloped”…

On a similar note, a defining portion of Western society is its music industry which has brought us talent like The Beatles, The Fugees, and even, dare I say, Kanye West. Is music not oral? I would argue the majority of popular music in Western culture is oral, relying on the lyrics to tell a story and take listeners into a new world of ideas and emotion.

“Oral culture” juxtaposed to “written culture” creates an “us” versus “them” mentality of othering. Chamberlin highlights this in his novel and in his interview. Both Chamberlin and the interviewer discuss the distinction of real and fake in story-telling, where cultures (Aboriginal and European alike) believe some stories hold more truth than others. I think “us vs. them”, “real vs. fake”, and “true vs. untrue” are cut from the same cloth in the context of “oral culture” versus “written culture”, specifically form a European-based mindset. Its tendency is to view “oral culture” as one which shares fables and folk tales – stories which hold little validity and fact, meant purely for entertainment purposes and/or to share a moral. In contrast, it views “written culture” as one which shares facts and meaningful information meant to inform and improve society.

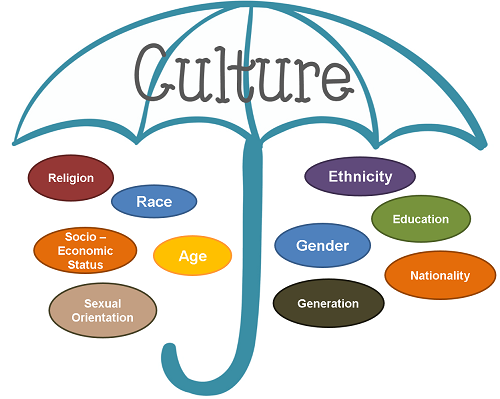

Culture is not defined simply by its mode of communication; one cannot say that a culture is either oral or literal because both mediums are found in every culture. If you met a Canadian who could only communicate orally and another Canadian who communicated only by writing would you say they were of two different cultures? If they differed in cultures, their defining differences would not be found in their communication, but perhaps more to do with which parts of Canada they’re from, or perhaps their ethnicity, or religion, or age. There are many aspects which make up a culture; however it is difficult to pinpoint a specific element as the definitive of a culture because culture is always changing and transforming. As a simple example, reflect on how much teenage culture has changed from the 1800’s to today. More complexly, reflect on how much Canadian culture has changed from the 1800’s to today. In both those examples, it would not be our first instinct to compare whether the cultures over the years were oral or literal. In order to answer the question from the latter example, we would probably think, “Well, what aspect of Canadian culture? Aboriginal Canadian culture? European Canadian Culture? Asian Canadian Culture? Female Canadian culture or Male Canadian culture?” Culture is complicated and has many defining features.

“Oral culture” vs. “written culture” creates an insurmountable divide, but culture is not always so divisive. Culture can be seen as a way to unite people who may otherwise have no similarities. Ideally, culture is inclusive and can offer opportunity.

____________

Works Cited

Chamberlin, Edward. “Interview with J. Edward Chamberlin”. Writer’s Café. Web April 04 2013.

Norman, Jeremy. “Transitional Phases in the Form and Function of the Book before Gutenberg: The Transition from Oral to Written Culture.” History of Information. Jeremy Norman & Co., Inc., 21 Aug. 2011. Web. 05 Mar. 2016. <http://www.historyofinformation.com/narrative/oral-to-written-culture.php>.

Courtney MacNeil, “Orality.” The Chicago School of Media Theory. Uchicagoedublogs. 2007. Web. 19 Feb. 2013.http://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/mediatheory/keywords/orality/