Bay Scallop Restoration in the Peconic Estuary

Background

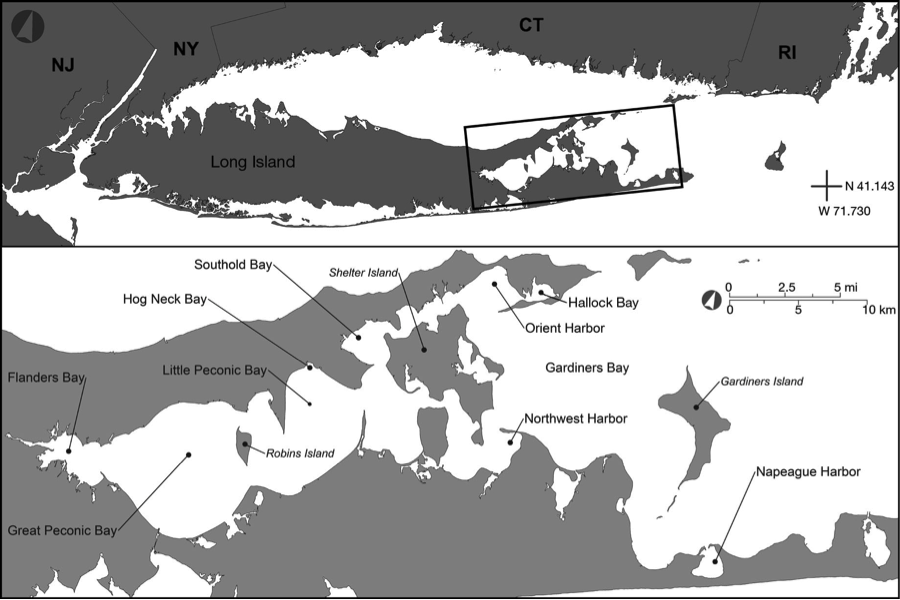

Located between the North and South ends of Long Island, New York, the Peconic Estuary consists of four bays and a surrounding watershed. Dubbed as one of the “Last Great Places” in the western hemisphere, the Peconic Estuary is an ecologically rich ecosystem supporting over a hundred species, including the bay scallops Argopecten irradians8.

A Special Shellfish

Bay scallops have brought great wealth and prosperity to Long Island since the mid 1600s. These bivalve mollusks are of vast importance to the local economy, tourist industry, and are a source of livelihood for the local baymen who extract these scallops as a source of income for their household9,11,1. As filter feeders, the scallops purify the water by continuously drawing in bits of algae and bacteria9. Additionally, as part of the food chain, the bay scallops are prey for animals such as mudcrabs and seabirds3. It is for these reasons that the Peconic Bay scallops are of great economic, social, and ecological value to the community of Long Island.

That is, until the start of their decline in 1986.

Learn more about the importance of bay scallops in the video below.

From Bivalves to Bye-Valves

Bay scallops have a relatively short life span of only two years and an unusual method of external fertilization that makes them exceptionally vulnerable to low populations and poor water quality10,3. A phenomenon called the “Allee effect” is commonly found in sparse populations, in which population growth is reduced by the increased difficulty of finding a mate3,11. With this in mind, the brown tide algal blooms that suddenly occurred in 1985 and continued into 1995 devastated the Peconic Bay scallop population. The scallops were pushed to the brink of extinction. This closed down the associated fisheries, putting most of the baymen out of work2,11. These harmful algal blooms turned the water dense and into the colour of coffee, preventing light from penetrating through11. As a result, the eelgrass meadows that had once densely populated the bay declined, taking with it the spawning and recruitment sites for many shellfish species, including the bay scallops2. The combination of eelgrass habitat loss, poor water quality, and low population density made it difficult for the young scallops to survive to spawning age. As a result of the severely decreased populations and poor environmental conditions, the bay scallop population was unable to recover from the brown tide.

Conservation Effort: Action and Involvement

After the initial brown tide wreaked havoc on the Peconic Bay, it was thought that the scallop populations would recover on their own, but that it would take at least a decade5. Despite this, even 12 years after the 1995 brown tide, the scallops showed no signs of recovery. Action had to be taken. In 2005, the Cornell Cooperative Extension a non-profit agency, and Long Island University received funding from Suffolk County to begin the Peconic Bay Scallop Restoration project1. The project was led by scallop biologists Stephen Tettelbach and Christopher Smith. The main purpose was to rebuild scallop populations in the bay to their pre-brown tide levels and in turn boost the scallop fishery. To do this, juvenile scallops were raised in a lab, and then released by hand in specific areas of the bay that have historically been home to large scallop populations. “No-take” spawning sanctuaries were put in place in these areas to protect the released scallops from fishing pressures.

Impact

Because of the life cycle of bay scallops, it would take at least 2 years for any progress to be seen after restoration efforts began. 2008 was the prophetic year that could make or break the program. Lo and behold, hard work payed off and the reported scallop landings were 3 times larger than they were before the project started7. It only got better from there. In 2010, the scallop landings were 13 times larger than they were before restoration7. At that point documented landings leveled off, but the yearly reported catches were still 10,000 to 15,000 kilograms more than they were from 1995 to 2007. The Peconic Bay scallop industry was back in business. But will it last?

What were the successes?

In the short term, the project has been successful in quickly building up bay scallops in the Peconic Estuary. There have been massive increases in scallop density and numbers, scallop survival, commercial fishery catches, income for fishermen and economic gains for the seafood industry11. Scallop larvae have been transported by currents and even populated other parts of the estuary that weren’t restored, and seem to be self-sustaining so far11.

The groups involved in restoration, including the scallop industry, Cornell Cooperative Extension, the State Department of Environmental Conservation, the Nature Conservancy and scientists did a great job of working together and pooling their resources towards rebuilding the scallop populations and making fishery management decisions cooperatively (Wayne Grothe, pers. comm., 10 March 2017). According to Wayne Grothe from the Nature Conservancy, fishermen were motivated and committed to sustaining the scallops. They helped to protect the spawner sanctuaries and waited for the scallops to reproduce before catching them, so that they would have more the next year.

“I think that the cooperation between all the different groups was exceptional. We all had the same goal and we worked together without too much conflict. Everybody was invited to participate and all were listened to.” – Wayne Grothe, The Nature Conservancy

Community involvement in the Peconic Bay area has had a massive impact on resource availability for the Peconic Bay Scallop Restoration Project. The SPAT Program, in which local volunteers grow scallops on their own docks to donate to the project, has been extremely successful in the area. In the 17 years the program has run, thousands of participants have been involved, amassing 13,000 volunteer hours each year (Kim Tetrault, Community Aquaculture Specialist, pers. comm., 25 March 2017). The regional Nature Conservancy also have 80 volunteers who partake in the release of juvenile scallops for the project (Wayne Grothe, pers. Comm., 28 March 2017). Overall, there has been widespread community engagement with the restoration project.

What were the shortcomings?

In the summer and fall, there are illegal poachers who take scallops before they have had a chance to reproduce. Scallop biologist Stephen Tettelbach said the state department environmental conservation officers are not showing enough enforcement to stop this, and illegal fishing could lower scallop populations (Stephen Tettelbach, in litt., 9 March 2017).

Another issue is that the scallop habitat is not healthy. For the scallops to thrive and be resilient in the long term, they need clean water and a healthy ecosystem. A brown tide biologist, Chris Gobler, says that one of the main factors that causes brown tide is nitrogen pollution in the water, since the algae that create brown tide thrive under high nitrogen levels (Chris Gobler, in litt., March 28 2017).

Watch this video to learn more about nitrogen pollution and brown tide.

The major sources of nitrogen pollution to the Peconic estuary are:

- Human wastewater from septic systems and cesspools makes up 40% of nitrogen loading to the estuary. In Suffolk County, 70% of homes are not hooked up to sewers and rely instead on individual septic tanks or cesspools, which were designed to remove pathogens, not nitrogen6.

- Nitrogen-containing fertilizers used on golf courses and agricultural lands enter the estuary via stormwater runoff (Christopher Gobler, in litt., 28 March 2017).

Action will need to be taken to reduce nitrogen pollution to improve water quality to prevent future brown tide blooms.

Besides water quality, eelgrass is another component to scallop habitat, which declined after the brown tides. Eelgrass plays an important role in purifying pollutants from the water and providing shelter from predators for young scallops11. The Cornell Cooperative Extension has attempted to restore eelgrass, but water quality has been too poor to yield much success (Wayne Grothe, pers. comm., 10 March 2017). Once water quality improves, future restoration of eelgrass will need to be continued.

Was it a success?

While we think this project showed short-term success in boosting scallop populations and the scallop fishery, it is uncertain how well the scallops would fare in the face of another brown tide. The project had the social engagement, resources and cooperation necessary to create immediate change for the scallops, however it is important to focus on the stressor – nitrogen pollution – that’s leading to brown tides in order to achieve long-term sustainability of scallop populations. So, it may not be a long-term success. Restoring water quality should be a first priority so that eelgrass habitat can recover and to prevent future harmful algae blooms. Improving water quality can also help to restore the whole ecosystem, so that it can support many populations and species. Otherwise, the scallops could be dependent on humans reseeding efforts and might not be able to survive on their own.

What can we expect in the future?

Since it is uncertain whether scallops could handle future disturbances, efforts to supply scallops to the estuary continue. Scientists from the Cornell Cooperative Extension continue to monitor scallop populations every year, and efforts will be continued to plant eelgrass further away from the coast where the water is less polluted and some eelgrass patches can survive. And for some hopeful news: in early 2017, it was announced that the state will be putting $7 billion towards creating sewer infrastructure for Suffolk County4.

For further inquires, follow the authors on twitter:

@EmmaGosselin3

@juliecduong

@PippusE

#OceanConsvnUBC

References

1Cornell Cooperative Extension (2017) Scallop Program. http://ccesuffolk.org/marine/aquaculture/scallop-program (accessed 21 March 2017).

2Dooley, P. (2006) Brown Tide Research Initiative: Report #9. New York Sea Grant Report.

3Fay, C. W., Neves, R. J., & Pardue, G. B. (1983) Species profile: life histories and environmental requirements of coastal fishes and invertebrates (Mid-Atlantic). Fish and Wildlife Service, 11, 12-24.

4Gernath, O. (2017) Sewage Treatment Finally has a Champion. http://libn.com/2017/02/07/gernath-sewage-treatment-final-has-a-champion/ (accessed 5 April 2017).

5Knudson, T. J. (1986) Long Island Gambles on a Scallop Transplant. http://www.nytimes.com/1986/09/16/nyregion/long-island-gambles-on-a-scallop-transplant.html (accessed 30 March 2017).

6Long Island Clean Water Partnership (2017) Problems. http://longislandcleanwaterpartnership.org/content.aspx?page=problem (accessed 5 April 2017).

7New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) (2016) Shellfish Harvest Limits. http://www.dec.ny.gov/outdoor/29870.html (accessed 28 March 2017).

8Peconic Estuary Program (2017) Overview of the Peconic Estuary http://www.peconicestuary.org/about.php (accessed 4 April 2017).

9Pickerell, C., Rivara, G., Manzo, K. P., & Scott, S. (2009) Town of Southampton eelgrass and bay scallop restoration planning project. Cornell Cooperative Extension Marine Program report.

10The Safina Center (2017) Bay Scallops Full Species Report. http://safinacenter.org/documents/2012/06/scallop-bay-full-species-report-here.pdf (accessed 20 March 2017).

11Tettelbach, T. S., Peterson, B. J., Carroll, J. M., Furman, B. T., Hughes, S. W. T., Havelin, J., Europe, J. R., Bonal, D. M., Weinstock, A. J., & Smith, C. F. (2015) Aspiring to an altered stable state: rebuilding of bay scallop populations and fisheries following intensive restoration. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 529, 121-136.