Kamila Kolpashnikova | Камила Колпашникова, 8 December 2018

While some housework tasks are done routinely, others are not. For some tasks, we give our daily attention, for others—only when it’s needed. The epitome of routine housework is cooking, whereas maintenance is usually regarded as non-routine. The 2003-2017 American Time Use Survey (ATUS)[i] data shows that about 57% of Americans report cooking or doing related tasks on the diary day. Compare that to only 6% of those who report engaging in maintenance or home repairs. Evidently, there are differences in how likely people are to report a certain activity on the diary day depending on whether the task is routine or non-routine.

However, if it might be easier to pigeonhole tasks such as cooking and maintenance, what about more ambiguous tasks like shopping? Shopping is sometimes classified as routine, and other times—as non-routine. Today, I will try to discuss a few ways to classify shopping tasks using ATUS.

Regularity of Housework

What actually constitutes routine housework and distinguishes it from non-routine? Routine tasks are often defined as tasks that need to be performed regularly. However, the question of how regularly a task needs to be done is not scrutinized often. Regularity can mean a wide range of things—performing a housework task every day, every hour, every week, every month, or even every year. In time use data, the concept of regularity tends to lean toward activities that are done every day because time use diaries are usually collected for a 24-hour day.

Some activities that are indispensable for our lives such as sleeping, eating, and visiting washroom are done every day with few exceptions. However, when it comes to activities which we potentially could do without, the concept of regularity starts to project a somewhat more relative character. In housework, for instance, people can certainly survive a day without doing any housework, and about 20% of the American population report not doing any housework on the diary day (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2018). Yet most housework is considered routine.

Cooking and cleaning are consistently categorized as routine housework tasks, but the confusion arises when we need to categorize shopping tasks. Not all Americans cook on the diary day—57% report that they did. Forty two percent report that they did some cleaning, and approximately the same proportion (43%) report shopping or spending time on services. On the other side, the quintessential non-routine task, maintenance, was reported by only 6% of Americans. Thus, if the regularity of a task is at the core of routine housework, shopping appears to cluster with routine tasks rather than non-routine.

How Regularity Reflects in Time Use Diaries?

The above percentages of Americans reporting doing housework do not reveal the weekly patterns of housework activities. The routine character of a task might also take its reflection in having no preference for the day of the week.

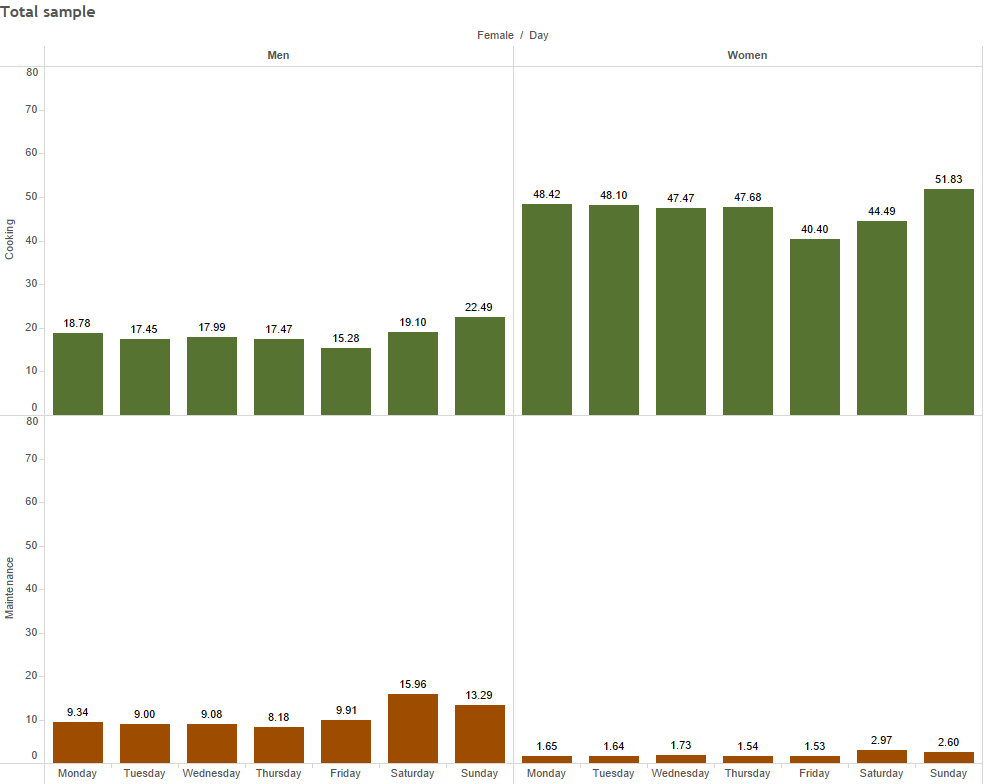

Figure 1 summarizes average time spent by American women and men on the relatively routine (cooking) and relatively non-routine (maintenance) tasks. The figure confirms that women spend considerably more time on routine housework than men, whereas men spend more time on non-routine tasks than women. Still, the patterns compared by week day are similar among women and among men. The least time spent on cooking is on Friday, the most time—on Sunday. Overall, the distribution of time over the week is quite flat—people tend to spend a similar amount of time on cooking throughout the week.

Figure 1 Quintessential routine and non-routine housework tasks by the day of the week and gender

As to the non-routine task, maintenance, the most time is spent on weekend days—Saturday and Sunday. The differences between the weekday and weekend participation are considerable (61% increase from Friday to Saturday among men, 94% increase—among women). Therefore, for non-routine tasks, we see that Americans not only spend comparatively less time in general, but they also spend considerably more time on such tasks on weekends.

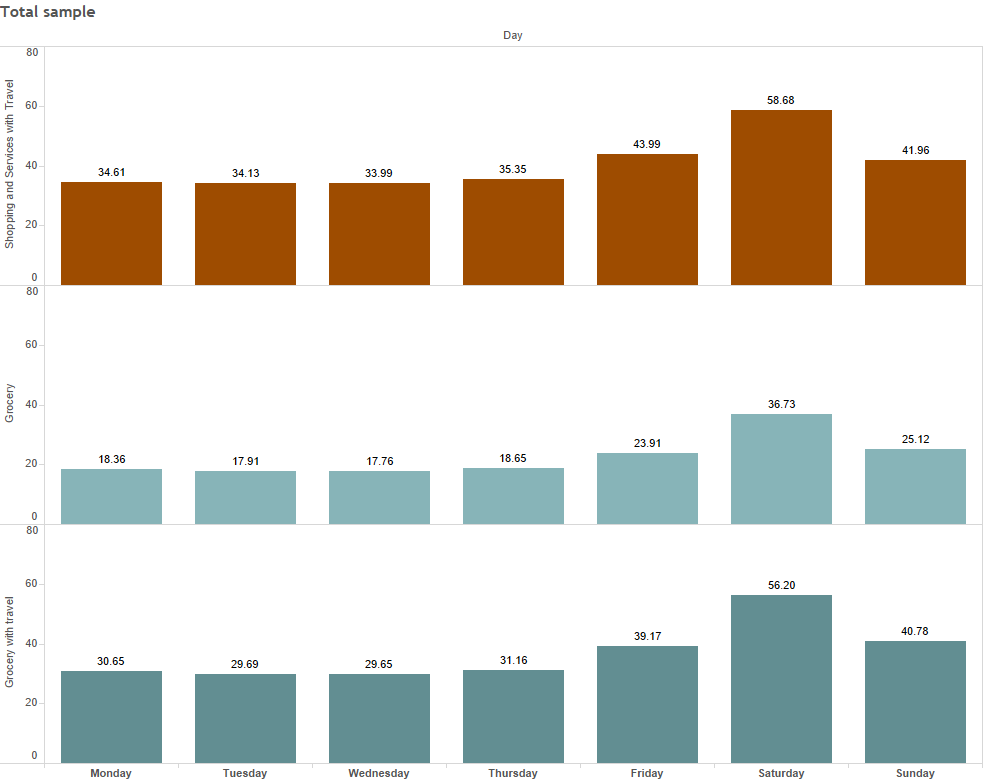

So what about shopping? The upper panel of Figure 2 shows that there is some increase in time spent on shopping and services on weekends, especially on Saturday. The increase, however, is not as stark as in maintenance tasks—33%—and a similar increase can be observed in cleaning tasks as well. Therefore, there can be two ways to classify housework in America:

- cooking as routine, and cleaning, shopping, and maintenance—as non-routine;

- cooking, cleaning, and shopping as routine, and maintenance—as non-routine.

Because of the similarities in participation of Americans in cleaning and shopping activities, these tasks cannot be classified into different categories.

Figure 2 Shopping and Services with travel time, Grocery shopping only, Grocery with travel time

Measurement is King

In this exercise, I measured shopping as the time spent on shopping and services (financial, governmental, legal, etc.), as well as included time spent on travel associated with shopping and services. The lower panel of Figure 2 shows also that a bigger share of my measurement is comprised of grocery shopping and associated travel. But out of that time, only approximately a half is the time spent on grocery shopping itself. If another researcher opts to use finer measurements of shopping, such as excluding travel time, waiting time, etc., it might as well be that such trimmed version of shopping tasks could have more affinity with maintenance tasks rather than cleaning.

Context is King

The meanings of doing shopping are context-specific, infrastructure-specific, economy-specific, culture-specific… There are cultures, where it is men’s work to buy groceries. There are countries, where there are so many convenience stores and online grocery delivery services that the travel time associated with shopping becomes negligible. It is important to remember that housework tasks can be routine in some contexts but non-routine in others.

Cite as: Kolpashnikova, Kamila (2018). What are the differences between routine and non-routine housework in time use data?

[i] Bureau of Labor Statistics (2018). American Time Use Survey 2003-2017. Washington DC. http://www.bls.gov/tus/.

nayan

September 10, 2023 — 10:39 pm

Nice blog

Samwilliam

September 13, 2023 — 3:48 am

Take the Kohl’s Survey and share your experience! Your feedback matters a lot. Please help us serve you better. Enjoy exclusive offers & discounts on your next visit. Join us in making Kohl’s your go-to shopping destination. Take the survey at https://www.kohlsfeedback.page/ and get a chance to win a $ 1,000 Gift Coupon. This offer is only for United States residents and Kohl’s Loyal customers.

gary

February 17, 2025 — 12:39 am

The Pollo Tropical customer satisfaction survey, which is available at pollolistens.com, is a shining example of how candid input can shape a better eating experience in a world where every consumer’s voice may result in meaningful changes. Pollolistens.com Survey

molcy

March 11, 2025 — 10:52 pm

Understanding consumer viewpoints and utilizing the input to make changes that improve subsequent eating experiences are the two primary goals of the study. Littlecaesarslistens Survey

kohlsfeedback com

June 5, 2025 — 1:51 am

The company’s private label credit card offers exclusive savings and expanded buying power. Kohlsfeedback com