Hello, fellow readers of Canadian Literature, and Dr. Paterson!

My name is Kevin, and I am a former Film Studies major (and former Ontarian), currently working as an arts administrator and children’s theatre instructor. I look forward to meeting you all and hearing your thoughts as our course unfurls throughout the term!

My initial thought upon registering for this course was a tinge of sadness at how tragically little exposure I’ve had to, effectively, most Canadian media output on the whole. Despite having taken 7+ years (and counting) of postsecondary arts education, pursuing Canadian content has been a despicably convenient blind spot throughout my adult and academic lives alike. If, as in the example of the Gitksan elder in Chamberlin’s introduction, we can understand a sense of belonging in a land by way of stories, I shudder to think of the kind of murky Hollywood vortex I have been inhabiting in my decades of life as a Canadian.

In part, I can attribute this to a culture of mass media convenience I have been recently working to counteract in my own life. Although the National Film Board of Canada has thousands of original Canadian titles available for streaming, there’s no ‘Canadian Cinema’ tab jumping out at us on Netflix. But I think the issue runs deeper than a comparative lack of exposure. My own understanding of Canadian national identity (and one echoed by many others in my life) has been one primarily of sheepishness and nonchalance in lieu of conventional patriotism. My own experience has found Canada to be a country better adapted for critique than pride – fitting, perhaps, for a country stereotypically associated with the word “sorry.” I’ve found these sensibilities reflected in most Canadian stories I have come across to date.

Unfortunately, as anyone who has been following the news this week will be all too well aware of, there is also somewhat of a brewing sense of Canada itself being out of synch with our own impressions of it – or, more aptly, what we are accustomed to idealistically constructing the nation as. The brutal arrests and conflict of the Wet’suwet’en people protesting pipeline construction on their traditional territory outside of Houston, BC – and, even more upsettingly, the corresponding media blackout, transparently attempting to quench news media circulation of the story – is as sickening to me as it is disquietingly unsurprising. As the story catalogues itself to the roster of similarly infuriating accounts in local news – absence of clean drinking water in reserves, and even, most horrifically, accounts of widespread forcible sterilisations among Indigenous women staying in Canadian hospitals – it becomes nauseatingly clear how ludicrous yet conveniently easy it is to construct cultural narratives of systemic mistreatment and abuse of Indigenous citizens being a thing of the past, and what vast and consequential steps would have to be taken to properly actualize on the aspirations of the national Truth and Reconciliation movement. As the course description has pointed out, the absence of circulated stories is as poignant and powerful as stories that are shared – and Canada, sadly enough, has thrived on doing just that, building a national identity of tolerance and inclusion on a bedrock of unceded land claims, systemic discrimination, and effective cultural genocide. Is it any wonder that the main connective tissue I’ve found in the Canadian literature I’ve pursued has been a sense of quiet, deep melancholy and regret?

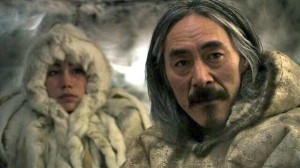

As such, I am particularly keen to dive into ENGL 470, both to help remedy the dearth of Canadian stories in my own life, and to teach me to be a more curious and active listener – both to the multiplicity and diversity of Canadian voices surrounding me, and to pay particular attention to the stories not being told. In beginning to investigate Thomas King’s The Truth About Stories, and his slyly repetitive circularity in reiterating his account of telling the story of the world on the back of a turtle to a variety of audiences, I’ve found myself reflecting back to my experience of watching Zacharias Kunuk’s The Journals of Knud Rasmussen over ten years ago. At the time, I had a vivid sense of the film – ponderously meditative, and with a beguiling circularity in plot, yet with a more intimately entrenched sense of place than almost anything I’ve seen since – being so fundamentally unlike anything I had ever seen before. At the time, I lacked the vocabulary to articulate how utterly unfamiliar I was with any mass cultural output by any Indigenous Canadians. Now, I look forward to rekindling that same feeling of discovering something so fundamentally new yet simultaneously deeply familiar – to listening, to learning, and to garnering a more holistic, rich understanding of my homeland in the process.

-KH

The Journals of Knud Rasmussen (dir. Zacharias Kunuk, 2006).

Works cited:

National Film Board/Office of Canada. https://www.nfb.ca/ Accessed January 10, 2019.

“The Wet’suwet’en and B.C.’s gas-pipeline battle: A guide to the story so far.” The Globe and Mail, January 8, 2019. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/british-columbia/article-wetsuweten-bc-lng-pipeline-explainer/ Accessed January 9, 2019.

Chamberlin, J. Edward. If This is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories? Toronto: Random House of Canada Limited, 2003.

King, Thomas. The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative. Toronto: House of Anansi Press Inc, 2003.

Kunuk, Zacharias (director). The Journals of Knud Rasmussen. Alliance Atlantis, 2006.

Virdi, Jaipreet. “Canada’s shame: the coerced sterilization of Indigenous women.” New Internationalist, November 30, 2018. https://newint.org/features/2018/11/29/canadas-shame-coerced-sterilization-indigenous-women Accessed January 10, 2019.