King’s novel Green Grass, Running Water remains a veritable treasure trove of clever, thinly-veiled allusions to socio-political and pop culture figures and events, playing on a web of intertextual knowledge for an enriched, heightened multi-layered literary experience. This is arguably never more the case than in the novel’s excerpt of characters reading and watching Western novels and films (pg. 207-219) – a veritable ‘supercut’ of characters weaving their own personal histories in an out of the experience and nostalgia of collectively watching and reading pulp Western novels and archaic Western films. As Charlie puts it, many of the above are pretty “standard stuff” – but King is also careful to unpack the seductive allure of the tacky, stereotypical pop culture presented, and that, no matter how monolithically rooted in stereotypes and tropes the Western is as a genre, there can still remain a sordid, seductive pleasure in participating in the culture industry and consuming its familiar, hackneyed narratives (even for audiences being most directly targeted and harmed by said stereotypes). Fittingly, Alberta, who spends her days lecturing on the horrors of Indigenous history, is the character who has the least patience for the televised Western – but even she is sucked into having its images hyperbolically grafted onto her dreams after idly flipping past the Western on TV.

In hyperlinking King’s narrative ‘supercut,’ I hope to further King’s practice of establishing a grander and richer sense of making meaning, the immeasurable interconnections of narrative and engaging with imbedded stereotypes across a variety of media (appropriately, it is hard to distinguish between the scenes in Eli’s Western novel and the film that the majority of the other characters passively flip to). Poignantly, for Charlie, this intersection between fiction and reality, past and present, and the overlapping impetus for real life experience manifests in a pointed nudge towards his character arc of finding meaning in reconnecting with his father by coming face to (racist prosthetic-covered) face with his father appearing in a derogatory, demeaning role in an old Western – a role that Portland himself would consider a high point of his life. King narratively alternates between Charlie’s flashbacks to the Western he is dozing off to – and, in an almost Birth of a Nation homaging feat of cross-cutting, the ‘soldiers’ in the Western ‘win’ in tandem with Charlie’s flashback of Portland being defeated (on and offscreen) by colonizing force. The conflation is unmistakable: the jingoistic frontier mythology of ‘cowboys win; Indians lose’ has ingratiated every permutation of Western culture, and will prove insidiously hard to unlearn, no matter how toxic.

The following hyperlinks show my attempt to unspool King’s myriad of references and intertexts in the aforementioned segment. Enjoy!

“Portland”

Currently understood as a hip, fairly ‘white’ American city, Portland, Oregon still heralds the 9th largest population of Indigenous peoples in the country, with nearly 60,000 people and 130 tribal affiliations. King’s employment of an American city as name (instead of the eponymous Canadian provincial ‘Alberta’ for one of the novel’s primary protagonists) not only aligns Portland with the ‘Americanization’ of his sadly thwarted career playing Indigenous stereotypes in Hollywood, but to the novel’s overarching theme of Colonization erasing any Indigenous past – as happened in Portland, Oregon, as around the province – in favour of being re-branded and reinterpreted in a post-colonial context.

“Remington’s”

A tacky cowboy restaurant that King (circa Charlie) describes as “Disneyland with food” – fittingly named after a firearms company, thereby directly homaging the automatic weapons that helped colonizers massacre and displace Indigenous communities throughout the lands now colloquially understood as North America centuries ago. Completing the demeaning circle of harm, Charlie and Portland work at Remingtons dressed not as cowboys, but as almost cartoonishly stereotypical ‘Injuns’ – so mired in embarrassing, stereotypical tropes that Portland reminds Charlie to “Remember to grunt […] The idiots love it, and you get better tips.”

“Sitting in front of the television”

King frequently employs this image of an Indigenous person, usually a man, passively transfixed by the television, as an instant cypher for depression, and in evoking the particular state of Indigenous people being overwhelmed and despairing in the face of centuries of compounding adversities impeding them from enjoying proper quality of life – as Portland does while defeated at numerous points throughout his stilted acting career, as depicted here.

“Four Corners”

The geographic intersection between four US states – Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado – and an area famous for being the ancestral homes of numerous Indigenous tribes, including the Anasazi, Navajo, Hopi and Ute. In a further in-joke, Remington’s (firmly affiliated with Colonial ‘white culture’) is located in a gentrified neighbourhood, while the neighbouring ‘Four Corners’ (which King codes affiliated with Indigenous life experience – effectively the homes and communities that European settlers would displace with their Remingtons) is painted as being in a much more downtrodden, underdeveloped and low-income area, thereby further reinforcing the ideological power discrepancy.

“As long as the grass is green and the waters run”

As Flick puts it, the statement is rampant with sarcastic sociopolitical intent, both recalling flowery language used in land treaty agreements used to displace and marginalize Indigenous people from their ancestral lands. The romanticized wilderness language is further ironic, Flick articulates, in the fact that Colonial development resulted in untold environmental harm, thereby endangering the qualifiers articulated in the statement itself (158).

“Doris”

A possible reference to Doris Day, singer and actor famous from the 1950s onwards, who starred in several canonical Westerns, including Calamity Jane (1953), The Ballad of Josie (1967).

“Blue shirt and a red bandana”

An iconic cowboy look, pioneered by John Wayne in numerous films, and referenced in numerous contemporary cultural intertexts, including Alan Grant in Jurassic Park. Charlie’s idolizing this look reinforces King’s overarching theme of the pervasive pleasure of participating in the culture industry, even at the expense of one’s own culture, history, and the systemic oppression of it.

“John Wayne”

Arguably the most iconic star of Western cinema – who, as Flick points out, increasingly has his hyper-masculine star identity conflate with being a swaggering, “injun-hating screen cowboy” (147). Further melding the layers of fiction and real life, King has Wayne actually cross paths with Charlie at Remington’s – a pristinely sour image of the quintessential fake movie cowboy lording over an actual Indigenous person disguised as a microcosmically fake ‘Injun.’

“Soldiers and peace and love”

King furthers his curt commentary on the dissonance between sweet, seductive language used by military authority figures in oppressing minority communities – primarily American Indigenous communities in this example.

“The white woman on the television began singing a song”

Many western films, such as Cat Ballou (1965), were also musicals, and used as vehicles to further star personas – often at the expense of trivializing their plots (and further indignantly reinforcing the harmful ideologies depicted therein).

“Straight from engagements in Germany, Italy, Paris, and Toronto, that fiery savage, Pocahontas!”

‘Pocahontas’ – arguably the most iconic figure of Indigenous people in Western pop culture (thanks largely to the 1995 Disney film, and, more recently as a tactic of racist and spectacularly crass, lowbrow bullying by President Donald Trump towards Senator Elizabeth Warren) – was a member of the Pamunkey tribe in Virginia. According to, in part, historical fact and Colonial legend, Pocahontas was married to Englishman John Rolfe, renamed ‘Rebecca,’ and paraded around England as an almost diplomatic mascot for English gentility – and, more harmfully, a symbol of the propensity of English culture to ‘civilize’ Indigenous cultures and people. King’s snide treatment of ‘Pocahontas’ as a faux-touring striptease act echoes the theme of ‘Pocahontas’ being a sleazy traveling act paraded around for ‘viewing pleasure.’

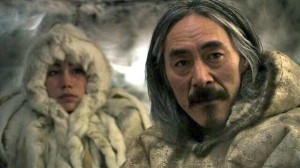

“[Portland] was wearing a black mask and he had done something to his nose and had painted it red. He looked silly”

Portland’s mask and red nose encapsulate many of the most harmful cartoonish ‘Injun’ racial caricatures. The abhorrently stereotypical costume is reified by Portland’s portrayal of the ludicrous stereotypes of Indigenous and First Nations people as ‘savage,’ ‘lusty,’ or almost feral. Portland’s degradation is calcified by this embarrassment being the only employment he can find as an actor, caricaturing his already caricatured early work portraying stereotypical ‘Native Chiefs’ in early Hollywood westerns – a final splash of salt in his irreconcilable wound.

“John Wayne took off his jacket and hung it on a branch”

Clear foreshadowing for the jacket the four elders later gift to Lionel, tenuously revealed (in the magic realism spirit of the novel) to have been Wayne’s actual costume piece. The jacket is similarly aligned with George as well, a similar brash, uncouth white character who occupies a similarly antagonistic and faux-superior role towards Indigenous communities, attempting to disrespectfully photograph the Sun Dance at the novel’s climax.

“On the bank, four old Indians waved their lances. One of them was wearing a red Hawaiian shirt.”

More foreshadowing that the four elders can somehow hop between the worlds of Western fiction and the ‘real world’ of the novel. Their ‘spying’ on Lionel specifically watching the film alludes to their eventual intervention into trying to ‘fix’ his life. Lionel, fittingly, is oblivious to this, ignoring the amazing rupturing of the fourth wall by plunging his head into his chest in existential despair, ignoring the film.

“Today is a good day to die.”

A phrase commonly attributed to Crazy Horse before the battle of Little Big Horn – but considered by many to have originated by a different Indigenous speaker at a different battle. Regardless, the phrase is now so imbedded into the cultural lexicon that it has become coopted by the Die Hard franchise – as inglorious a fate of sordidly ironic cultural appropriation as any.

“Iron Eyes”

A clear, tongue-in-cheek allusion to ‘Iron Eyes Cody’ – an Italian-American actor who gained consistent work as an actor by impersonating First Nations and Indigenous characters in Westerns and comedies. C.B. – Portland’s actor friend – is clearly patterned after Cody.

“Iron Eyes Cody” – or, as his birth certificate would have it, the Italian ‘Espera DeCorti.’ One of Hollywood’s most famous ‘Fake Indians,’ and genesis for King’s ‘C.B.’

“Bursum.”

In creating Bill Bursum, Lionel’s boss at the video store, as Flick notes, “King combines the names of two men famous for their hostility to Indians” (148): Holm O. Bursum, New Mexico senator, who proposed the “Bursum Bill” – a piece of legislation designed to irrefutably lend colonists “squatters’ rights” on Indigenous lands, and Buffalo Bill Cody, purveyor of the infamous sideshow exploiting First Nations people as carnival entertainment – a clear predecessor for the kind of shill, hack entertainment and dismissive superiority towards Indigenous people championed by Bill Bursum in King’s novel. Bursum’s being aligned here with John Wayne having a jingoistic victory over the Indigenous characters in the Western movie that unites all the characters is a clear conflation of white privilege trampling over Indigenous rights, both crowing proudly while doing so.

WORKS CITED

A Good Day to Die Hard (film). Dir. John Moore. Twentieth Century Fox, 2013.

Barber, Sally. “Native Cultures of Four Corners, Arizona.” USA Today. Web. Accessed on March 17, 2019.

Cat Ballou (film). Dir. Elliot Silverstein. Columbia Pictures Corporation, 1965.

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161/162 (Summer/Autumn 1999): 140-172. Web. Accessed on March 15, 2019.

Hamilton, E.L. “The True Story of Pocahontas.” The Vintage News. Web. Accessed on March 17, 2019.

“Iron Eyes Cody.” IMDb: The Internet Movie Database. Web. Accessed on March 17, 2019.

Jurassic Park (film). Dir. Steven Spielberg. Universal Pictures, 1993.

King, Thomas. Green Grass, Running Water. Toronto: HarperCollins Publishers Ltd., 1993. Print.

Krieg, Gregory. “Here’s the deal with Elizabeth Warren’s Native American heritage.” CNN. Web. Accessed on March 16, 2019.

Osife, Maiya. “The roots of Portland’s Native American community.” Metro News. Web. Accessed on March 16, 2019.

Pocahontas (film). Dir. Mike Gabriel & Eric Goldberg. Walt Disney Pictures, 1995.

Remington Arms. Web. Accessed on March 16, 2019.

Takatoka, as told by Lee Standing Bear Moore. “Today is a Good Day to Die.” Manataka Indian Council. Web. Accessed on March 17, 2019.

“What was the Bursum Bill?” Study.com. Web. Accessed on March 17, 2019.