Carlson writes:

“Harry Robinson’s account of literacy being stolen from Coyote by his white twin conform to all the standard criteria associated with a genre of Salish narratives commonly referred to by outsiders as legend or mythology with one exception – they appear to contain post-contact content” (56).

Why is it, according to Carlson and/or Wickwire, that Aboriginal stories that are influenced or informed by post-contact European events and issues are “discarded to the dustbin of scholarly interest”? (56).

“I want to get rid of the Indian problem. Our object is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic, and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department.”

-Duncan Campbell Scott, Deputy Superintendent-General of Indian Affairs, 1920 (qtd. in Kariya 195)

Whoof.

Scott’s vitriolic, fire and brimstone words may evoke instant flinches of anger or disgust in a contemporary context. Nonetheless, they proved microcosmic of a disconcertingly common practice of his time (and one that, more than we’d care to admit, extends far beyond to a contemporary epoch): namely, that of Colonial political policymakers of predominantly European descent managing Indigenous and First Nations communities and people. In short, making decisions on their behalf, generally without consulting them (or often by outright harmfully discriminating against them), bereft of courtesy and empathy, and generally effectively treating the lives, living situations, cultural presence and lineage, and essentially quality of life of enormous communities of people with the comparative humdrum flippancy of a rung of agriculture or trade.

I’d argue that hindsight (but, again, these attitudes are far from exclusively rooted in the past) demonstrates two main predominant attitudes of exactly how said Colonial policymakers aimed to manage the people whose lands they were in the midst of setting up shop on: namely, as Thomas King might put it, either erasure or taxidermy. To some, the Indigenous and First Nations people were, as Scott succinctly spat, a “problem,” to be simply assimilated or otherwise stamped out. To others, the land’s initial residents were seen as effectively a walking talking ethnographic diorama. Their lives and cultures were to be preserved and cherished… insofar as they fulfilled the stereotypical image of how European Colonists envisioned them, and without any consideration of how said people might actually want or need to live. Both, as King puts it, “ree[k] of unabashed ethnocentrism and [sometimes…] well-meaning dismissal” (“Godzilla vs. Post-Colonial 184). And, ultimately, regardless of intent, history has shown the latter attitude to be, in many ways, largely just as harmful as the former.

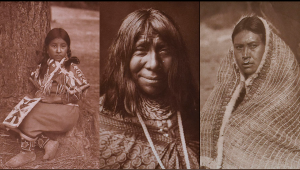

Examples of Edward Sheriff Curtis’ Indigenous photography – King’s so-called “pretend Indians.” Curtis’ website, I see fit to point out, still carries the auspicious byline “A True Friend of the Indian” on google. I’ll just leave that here.

The editorial biases that Wendy Wickwire finds in Franz Boaz’ ‘sanitation’ of Indigenous storytelling, removing any faux-‘anachronistic’ language such as the word “gun” (or the elimination of more contemporary Indigenous stories from collections or chronicling altogether) to substantiate the illusion of all Indigenous stories being timeless, age-old fables (Wickwire 23) is a perfect example of exactly that same form of cultural erasure. It is the literary equivalent of Edward Sheriff Curtis’ Indigenous photoshoots, which, as King points out, were as much a game of dress up as a form of ethnographic documentation (The Truth About Stories 32-33). King later describes the kind of ascribed performativity of Curtis’ staged, stereotypical traditional costume-clad photoshoots as “a kind of ‘pretend’ Indian […] dressed up in a manner to substantiate the cultural lie that had trapped us” (The Truth About Stories 45). And, I think it’s safe to say, the ongoing pop cultural presence of this same ‘pretend Indian,’ satirical or not, shows the shelf-life and disastrous racial prejudice ripple effects from the cultural identity ideological constructed by Curtis, Boaz, and others.

Curtis’ ‘pretend Indian’ hyperbolized into ‘comedic relief’ racism in The Simpsons… in 2003. D’oh…!

King has two main salient points in his above remark: one, that projects such as Curtis’ and Boaz’ further reify the image of all Indigenous and First Nations people as an antiquated stereotype, furthering their being anchored in Canadian culture as functionally ‘a thing of the past’ – and, secondly, that generations of subsequent Indigenous and First Nations people would then need to, themselves, perform the ascribed stereotype to attain any bastion of Indigenous authenticity (as King himself experienced in his university years). As King puts it, it may be a lie, but it is one that serves to trap future generations, in terms of both external and internal cultural and aesthetic identity, all the way into present-day. And, to add insult to injury, the archaic aesthetic that Boaz and Curtis ascribe to their chronicling of Indigenous and First Nations words and images feeds into the domineering cultural pitfall of the assumed myth of ‘progress’: that Indigenous and First Nations culture (whether assumed to be good or bad) is antiquated, or ‘old-fashioned’ (hopefully people at least resist from using the word “primitive” now…). This, as King sombrely points out, is not only disastrously harmful in terms of contemporary treatment of Indigenous and First Nations people, but it serves to further bifurcate and emancipate individuals and communities from their actual cultural traditions, which may or may not fit the stereotypical marketing mould of ‘the Indian white people had in mind’ (“Godzilla vs. Post-Colonial” 185).

Of course, cultural images shape perception which shape sociopolitical treatment – and history also saw clear examples of how such well-meaning ethnocentrism could result in even more disastrous quality of life for the people purportedly intended to be protected by it. As King points out, the people Curtis was documenting were generally thought to be “poised at the brink of extinction” (The Truth About Stories 33). But, as Theodore Binnema and Kevin Hutchings argue, this attitude was corroborated by many Romantic European intellectuals during the era of Colonialism, cultivating the now infamous stereotype of the “noble savage” (116). Many of these well-intentioned European-intellectuals-turned-Canadian-policymakers, such as Sir Francis Bond Head, strove to protect the ‘noble, natural purity’ of Indigenous and First Nations communities from what they saw as the corrupting influences of European culture – the effect being an even further emancipation of First Nations communities from their ancestral lands to inhospitable new living spaces due to the desire to whisk them away from supposedly harmful European influence (122). Well-intentioned or not, these gestures demonstrate the same overreach of controlling Colonial cultural puppeteering, making decisions on behalf of Indigenous and First Nations communities, which, whether intended to be for their benefit or not, were only further building blocks towards the same project of presumed ‘extinction.’

So, the age old question: how do we move forward? As always, I welcome any thoughts and insights, but, to me, King has, himself, coyly provided the most astute answer to all non-Indigenous people weighing in: stop trying to put words into the mouths and imperiously make decisions on behalf of Indigenous people, and allow them to contribute to their own conversation. King’s genre classifications of Indigenous “interfusional” literature, like Wickwire’s chronicling of Harry Robinson’s stories, or “associational” stories – which King even articulates as being a clear entry point to learning about Indigenous culture and stories for non-Indigenous readers (“Godzilla vs. Post-Colonial” 186-187) – are a great starting point to a better sense of an ‘authentic’ Indigenous experience than the curated ethnographic stereotypes of Curtis or Boaz. Listening and learning to the accounts of actual people and communities, to me, seems like the most tangible and proactive steps for non-Indigenous Canadians to take towards complicating and reshaping ‘the Indian they had in mind.’

-KH

WORKS CITED

Binnema, Theodore and Hutchings, Kevin. “The Emigrant and the Noble Savage: Sir Francis Bond Head’s Romantic Approach to Aboriginal Policy in Upper Canada, 1836-1838.” Journal of Canadian Studies 39:1 (Winter 2005). 115-138. Web. Accessed on September 27, 2018.

Carlson, Keith Thor. “Orality and Literacy: The ‘Black and White’ of Salish History.” Orality & Literacy: Reflections Across Disciplines. Eds. Carlson, Kristina Fagna, and Natalia Khamemko-Frieson. Toronto: Uof Toronto Press, 2011. 43-72. Print.

Edward S. Curtis Gallery. Web. Accessed on February 18, 2019.

Kariya, Paul. “The Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development: The culture-building process within an institution.” Place/Culture/Representation. Eds. James S. Duncan and David Ley. London: Routledge, 1993. 187-204. Web. Accessed on December 9, 2018.

King, Thomas. “Godzilla vs. Post-Colonial.” Unhomely States: Theorizing English-Canadian Postcolonialism. Mississauga: Broadview Press, 2004. 183-190. Print.

—. The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative. Toronto: House of Anansi Press Inc, 2003.

“The Bart of War” (Television episode). The Simpsons, Season 14, Episode 21 (Originally aired May 18, 2003). Web. Media clip accessed on February 18, 2019.

Wickwire, Wendy. “Introduction.” Living By Stories: A Journey of Landscape and Memory. Author Harry Robinson; Ed. Wendy Wickwire. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2005. 7-33.

Great post, Kevin. Thank you.

I really agree with you that it’s essential for all settler-Canadians to make space in their lives to listen to Indigenous voices. I read majority Indigenous news sources, listen to Indigenous podcasts, and fill my life with Indigenous literature. I make time for Indigenous events, where my priority is always to listen, and I centre the perspectives of my Indigenous friends and family in my work and life. It shapes my relationship to myself and the communities I live in in big ways. And, since making these changes 6 or so years ago, I’ve grown, learned, and especially unlearned soooo much. Unknowingly, I’d say harmful things and it’s a gift to recognize that more clearly now.

My favourite paper on decolonization is Decolonization is not a metaphor by Eve Tuck and K. Yang. They offer some very meaningful guidance and clarity.

You can read it here if you’re interested: https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/18630

Take good care today-

Georgia

Hi Georgia,

Thank you so much for your kind words, and for sharing your experience. I think your paradigm shift in terms of seeking out and embracing Indigenous media and content in your life is inspiring, and a wonderful example to how the rest of us could learn to better listen (and, as you astutely say, ‘un-learn’). Thanks also for sharing the Tuck/Yang article – I will check it out! Take care, and thanks again!