Integration and the Taxation of Passive Income: An Economic Perspective

by kevinmil

Notes prepared for the Canadian Tax Foundation conference “Tax Planning Using Private Corporations: Analysis and Discussion with Finance,” held in Ottawa on September 25, 2017.

Kevin Milligan

Vancouver School of Economics

kevin.milligan@ubc.ca

This presentation concerns the Department of Finance proposals on the tax planning by private corporations. The discussion document can be found here.

The spreadsheets on which the analysis here are based can be found here.

The Powerpoint slides can be found here.

Introduction

“The system would neither encourage nor discourage the retention of earnings by corporations”

This was the goal set out by the Carter Commission 50 years ago for the integration of the corporate and personal tax systems.

“…neither encourage nor discourage the retention of earnings by corporations”

The goal embodied in that quote is neutrality. Neutrality is at the centre of the concept of economic efficiency. A neutral tax system means that people make the same decisions in the presence of taxes as they would in a world without taxes. Neutrality means that government has the lightest possible touch; business decisions are made on business merits, not pushed one direction or another by tax considerations.

Is neutrality a lofty idealistic academic goal? Of course. Along the road to any goal, we need to confront the concerns of on the ground reality. Concerns of administration. Of complexity. And of practical issues of tax law. These factors can and should determine how far down the road we go toward this goal.

But let us start first with deciding down which road to travel. I think this benchmark—“neither encourage nor discourage”—set out by Carter is a good one. Over the next few minutes, I will explain why I think this is a good goal, then explore how good a job these proposed reforms do in achieving this goal.

What is integration?

Integration means that tax at the personal level should reflect tax already paid at the corporate level.

Put differently, all paths for a $ from “profit to pocket” should bear the same tax.

If integration holds, there should be no financial gain from readjusting the location of savings. Again, recall Carter:

“The system should neither encourage nor discourage the retention of savings by corporations.”

Why integration?

Integration supports neutrality: we want people making the same decisions as they would without taxation. This is a free-market goal and the literal economic definition of an efficient tax.

Firm owners decide to save inside the firm for a variety of reasons: retirement, maternity leaves, ‘buffer’ savings, saving for a future reinvestment. This is all fine, but the tax system should neither favour nor disfavor any of these choices. These decisions should be made on business merits, not pushed one way or the other by taxes.

It is useful to remember the reason we have the Small Business Deduction. The introduction of the SBD was explicitly meant to facilitate active investment. That’s the reason laid out in the 1971 budget speech by Edgar Benson.

If a corporation employs the tax savings that result from the low rate for non-business purposes, such as Portfolio investments, a special refundable tax will be imposed to recover the low-rate benefit.

We intend that the small business incentive be available only to Canadians and that it encourage Canadian ownership of our expanding businesses.

Ways Current Integration Falls Short

The current system of integration falls short of an academically pure neutrality in a variety of ways:

- It’s notional; doesn’t reflect actual taxes paid.

- One national gross-up rate.

- Tax-exempts like RPP/RRSP can’t claim DTC.

- Capital gains rate currently ‘too low’ compared to dividends/wages.

- Firms claiming SBD have a ‘head start’ deferral advantage for saving.

The current proposals really only address the last of these. The aim here is not perfection, but to try to make an imperfect system a bit less imperfect. That’s a fine goal.

Do proposals improve integration?

I will present some analysis of the proposals on passive income. I focus on high-bracket investors for a few reasons:

- High bracket investors are much more likely to have large passive portfolios.

- Current system imposes a high flat tax on passive income, so low/mid bracket investors are already disadvantaged. Not clear it makes financial sense for them to save inside a corporation under the status quo.

But, it should be acknowledged that the proposals will make saving inside a CCPC even worse than the status quo for a low- or mid-bracket investor.

The current system is ‘over-integrated’, meaning that the credits given for tax paid inside the firm are too high. The proposed remedy is to remove the refundable dividend tax on hand (RDTOH) notional amount that is currently included when dividends are paid out.

Some have argued that the resulting tax rate on passive income inside the firm is excessive. But, any analysis needs to look at the whole flow of income from beginning to end. Inside the firm the taxation of the principal is very light to start, so the heavier taxation of the accruing income balances things out.

I will offer two pieces of evidence on integration under the current and proposed system.

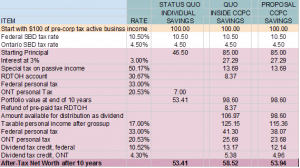

First, I have independently redone the analysis appearing the Finance discussion document Table 7. My analysis can be found online here.

My analysis starts with $100 of pre-tax active business income and watches what happens when it is retained inside the firm or immediately distributed over a 10 year period. Under the status quo, the individual is about 10% better off saving inside the firm as outside the firm. With the proposal, there is virtually no difference for saving inside and outside the firm.

This can vary a bit depending on time horizon and the mix of assets held. However, in my analysis the reform is fairly successful at removing the current deferral advantage of saving inside the firm.

The second piece of evidence is simple observation. If a system is properly integrated then, as per Carter, there should be neither advantage nor disadvantage from retaining earnings.

I observe the following. The financial planning industry in Canada makes a strong pitch to firm owners that there is a deferral advantage for saving in CCPCs. This pitch is not hard to find—a simple google search reveals dozens of examples.

http://lmgtfy.com/?q=doctors+canada+incorporation+deferral+advantage

If there is a deferral advantage, then the system is not currently properly integrated. If you claim there is no deferral advantage, then the ubiquitous pitch made by financial planners is wrong. I do not think this pitch made by financial planners is wrong. There is a current deferral advantage and that means the system today is not properly integrated.

How much do the proposals matter?

The last point I’d like to make is to emphasize the scale of the impact of the reform. I will do this in two ways—first with a simple example then a slightly more involved example.

First, the simple example. Imagine $100,000 in a passive portfolio paying 5% interest income. The change in tax for an Ontario high bracket tax payer can be calculated as:

- There is $5,000 of passive income.

- RDTOH on the $5,000 is 30.67%, or $1,534.

- But, this is taxed as non-eligible dividend income. 45.3% effective rate for Ontario high bracket

- So, RDTOH is worth $838 after tax if flowed through to the individual immediately.

- This is <1% of the total value, but does eat up 17% of the return.

- After 10 years, this can affect terminal value of the portfolio by 8-15%.

Is this large or small? That’s in the eye of the beholder, but I think it’s important to keep the scale in mind.

Now the slightly-more-involved example.

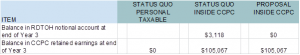

Imagine someone saving $33,333 per year for three years. This could be for the purposes of a reinvestment in the firm, a maternity leave, or for eventual consumption purposes outside the firm.

Imagine again that the savings earn interest income at 5% per year. This income is taxable each year as passive income. Here is what the account looks like at the end of three years.

The balance is $105,067. There is also a balance in the RDTOH account of $3,118. This has an after-tax value of $1,705.

Two points to make.

First, for money reinvested in the firm there is no change to cash flow. There is no less cash available for a maternity leave or a reinvestment. The RDTOH account is notional, so it only affects cash once there is a dividend paid eventually.

Second, because of the removal of RDTOH, the change in the after-tax value of the portfolio because of the reform is $1,705, or 1.6%.

So, for those using a passive portfolio to save short-term within the firm, there is no change to cash flow and a fairly small change to the portfolio value.

Concluding thoughts

“The system would neither encourage nor discourage the retention of earnings by corporations”

My job here, as an economist, is to help us figure out what goals to set for the tax system. I think this goal, as laid out in the Carter Commission, is a sound one. At its core, integration and neutrality mean that business decisions can be based on business merits.

Of course, in deciding how far to go toward any goal, we need to weigh the costs and benefits. There are lots of important challenges that await.

- Transition: how grandfathering will work.

- Inter-company shareholdings and investments in startups.

- I’m sure we will hear more today!

I’d like to emphasize that these concerns are serious. If there are problems, we need to see if Finance can fix them. If they can’t be fixed, certain elements of the package will then need to be reexamined. But, these issues are much more the purview of the lawyers and accountants among us than the economists. I have a suspicion you won’t need my encouragement to speak up on this as the day proceeds. I look forward to hearing what you have to say.

Thank you!