Kevin Milligan

Professor of Economics

UBC Vancouver School of Economics

kevin.milligan@ubc.ca

May 31, 2019

Discussion of the papers in the CEA session “Promises and Prospects for a Guaranteed Basic Income in Canada / Promesses et perspectives d’un revenu de base garanti au Canada”

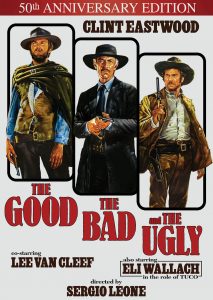

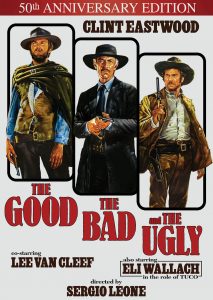

Basic Income: The good, the bad, and the ugly.

Thanks to the presenters and to Kourtney Koebel and Diane Pohler for organizing this session.

I’ve organized my discussion of the presentations into three parts: the good, the bad, and the ugly.

The Good:

Let’s start with the good.

The recent wave of advocacy and research on basic income has brought forward several things that I think are good, and you can see these good aspects in these papers.

Foremost in my mind is a focus on poverty alleviation; ensuring that those who are struggling have sufficient income to meet their reasonable needs and participate fully in society. You can see this focus on poverty alleviation in all four of the presentations here today.

Another good aspect is figuring out ways to consolidate and rationalize our existing tax and transfer system into more coherent structures. There is duplication and redundancy. This complexity and overlap can lead to unintended-harsh incentives and renders our system opaque to those who don’t have accountants to sort out the problems. Moreover, theoretical models of optimal income taxation often treat the tax and transfer system as a unified structure, so thinking about how to turn our system more into a negative income tax-like system can help to fill in the gap between theory and reality. All of the empirical work presented today does this in various ways, and it’s a solid contribution.

Finally, providing hard numbers is good. Having numbers on the structure of potential basic income programs and what they would cost is crucial for the public to evaluate whether they are worthwhile. The presentations today are all based on hard numbers, and these numbers that help to move the policy discussion onto firmer ground. That is good!

The Bad:

Many models of basic income foresee the basic income displacing social assistance, pensions, unemployment insurance, and other income supports. The idea is to take all of these programs and put them in one big basic income bucket. In the US, I’ve seen the Medicare and Medicaid health insurance expenditures lumped into the basic income bucket too.

The basic income models presented here have been much more of the Negative Income Tax style, and the Boadway Cuff and Koebel paper explicitly discusses the role of straight transfers vs social insurance, arguing that both should likely coexist beside each other.

I agree with BCK on this, because models of basic income that aim to put all social insurance programs into one basic income bucket are bad.

Why are they bad? For two reasons.

First, the different programs we have respond to different risks and different needs. It is hard to imagine one basic income bucket meeting all these needs. Moreover, if you tried to replace them all with one program and missed the mark, we’d soon enough see these programs sprouting anew to respond to the basic needs and demands of the population for social insurance. When observing the proliferation of programs, it may be wise to consider that at least some of that multitude exist for solid reasons; separate reasons.

The second reason why putting social insurance in the basic income bucket is bad is because insurance programs pay out based on need. You get EI if you are unemployed. You get disability supports if you are disabled. You get GIS if your life lasted longer than your savings. It is a very bad idea to replace these programs with a straight lump-sum transfer across all citizens independent of need—which is the basic premise of basic income.

To understand why, consider disability payments under provincial Social Assistance programs. For most (if not all) provinces, the disability component of SA has more recipients than the regular SA program. Right now, if you are a low-income kid with a disability, you can get a wheelchair if you need it. With a Rawlsian mindset, we should imagine that could happen to any of us or any of our kids. I think we want a world where a low-income disabled kid can get a wheelchair.

If you instead cancelled all Social Assistance payments and put them in a basic income bucket, that kid doesn’t get a wheelchair. He gets a cheque for his per-capita share of a wheelchair. He doesn’t need that cheque, he needs a wheelchair.

Cancelling social insurance to fund a basic income is the privatization of social insurance and would be a very bad move.

To repeat, the basic income models presented here today were not of this type, but many other basic income proposals do try to replace social insurance programs in order to fund them, and in my view such efforts should be treated with high skepticism.

The Ugly

I think there are three basic ugly truths that we must confront about any basic income schemes.

The first is that the numbers for basic income schemes are tough. And by ‘tough’ I mean that almost surely impossible to make work. This is very clear in the numbers presented here today. We see large increases in transfers to the bottom three or four deciles, paid for by very large increases in taxes in the middle and upper deciles.

There is some appetite to ‘soak the rich’ to be sure, but these proposals presented today are funded more by heavily increasing taxes on the middle class than the rich. I think it is very hard to argue that a basic income program funded by cutting the incomes of families making only $55K a year by 5% or more is a good deal.

I don’t think this is the fault of the capable and smart researchers who wrote the papers we saw presented today. I think the task—to fund a massive increase in transfers to low income families without a massive increase in taxes—is almost impossible.

This doesn’t mean anyone should stop advocating for a massive increase in transfers to low income families. It does mean that calling the transfer program a ‘basic income’ doesn’t allow you to avoid the ugly math.

The second ugly truth is that designing and administering a basic income scheme is really, really hard.

The negative income tax proposals we saw today would all be delivered through the income tax system. That’s a good and feasible way to do things, and I think that is likely the best way to go.

But let’s be clear, there are challenges with using the tax system. There are nonfilers who would slip through the system. There is also timing: if you suffer a negative income shock today on May 31, 2019, you wouldn’t see any change to your basic income cheque until after your next tax filing; so perhaps one year later.

Another ugly design challenge is the definition of the family unit. This may strike you as trivial—and I didn’t see serious consideration of it in the papers presented today. But it is actually a central and vexing challenge for basic income models.

As I understand the proposals today, they would be focused on the tax-filing unit, being the parents and any under-18 children. But, families and people live in a variety of ways. If you focus on the tax-filing unit, that means that a 19 year old living with their parents would be an independent family unit for the purposes of the basic income.

If you are going to ask families in the 5th decile to take a 5% cut to their incomes in order to pay for a basic income, I think many of those 5th decile families would be interested to know if the recipients of the basic income is going to be 19 year olds living with their parents. This is not trivial—I ran some microdata simulations a few years ago suggesting that Ontario’s basic income pilot would pay out between half and 2/3rds of its funds to over-18 adults living with their parents. Maybe that’s a good idea—but also maybe many voters would find that to be a tough sell.

The third ugly truth is that the ‘pilot’ approach to learning about basic income is likely a dead end. It’s a dead end because what we learn from them is very limited compared to the cost. In Wayne Simpson’s presentation, note that sample sizes on many of these pilots. One has only 100 families! Why are the sample sizes so small? It’s because the pilot programs are very expensive. $1000/month for two years would cost $24 million for just 1000 people. And it is empirically very hard to learn much from just 1000 people. I don’t think more basic income pilots are going to yield very much useful information.

The path forward

Let me end on a more positive note. Here are four things I think would be a productive focus for research and policy advocacy.

First, we should continue the focus on poverty alleviation. This means targeting transfers based on family income and family situation. It also means that we must continue to make the case that poverty alleviation is important.

Second, we should continue the work on NIT-style consolidation of credits and taxes into a more coherent system. The resulting amounts may not be enough to fully fund a ‘basic income’, but it is still worth doing.

Third, we should make use of quasi-experimental and non-experimental evidence where available to learn about the impact of income transfers.

Fourth, if we are doing experiments, they should be tightly focused on clear questions. They should aim to build a base of evidence brick by brick and not try to do everything at once.

Thank you and I look forward to the discussion.