Canada’s Fiscal Federation: The Next 50 Years

Kevin Milligan

UBC Vancouver School of Economics

John F. Graham Memorial Lecture 2017

Dalhousie University

November 30, 2017

Draft Script

Slides can be found here.

A PDF of this script can be found here.

- Introduction

Slide 1: Title slide

Thank you for the introduction.

Slide 2: Pier 21: The Canada we Choose

My grandfather worked here back in the 50s and 60s in the Pathology lab over on University Avenue. One of his jobs was food safety testing for a local dairy. Sometimes, on a Friday, he would take a brick of ice cream home to his family across the ferry in Dartmouth. It’s one of my mother’s cherished memories of childhood. One question I always had about this family story though—were the ice cream bricks my grandfather got to take home the ones that passed the test, or the other ones?

My mother’s family arrived here in Halifax in January 1945 by plane and train from Bermuda. So many other immigrant families arrived here down on the Harbour on Pier 21. All of them chose Canada; any many chose Nova Scotia.

Think back to what they saw 50 years ago.

Looking forward: a country of opportunity. A good place to settle and raise a family. They chose Canada; they chose Nova Scotia. What kind of place did they build over the next decades?

Now consider us, here in this room. What kind of country will we build over the next 50 years?

A society is composed of many parts, but what we do together as a society through government represents about 40 percent of our economic activity. I’m a public finance economist, so I’ll focus on that 40 percent this afternoon.

The namesake of this lecture, Professor John Graham, was a scholar of municipal and provincial public finance. Today, my lecture will take inspiration from Professor Graham’s legacy and consider how we organize our public finances across different orders of government.

I will start by pointing out what we’ve built over the last 50 years. I will argue that we have chosen to build a radical federation, and that we have done it well.

Next, I will focus on the great challenge our radical fiscal federation faces over the next 50 years, driven by provincial responsibility for healthcare spending.

I’ll then offer an economic framework for addressing this great challenge, and finally present my preferred policy solution.

2. A Radical Federation

Slide 3: Get Radical Canada!

We Canadians are radical. Over the last 50 years, we choose to create a radically-decentralized fiscal federation.

When my family arrived in 1945, provincial governments in Canada collected less than 10 percent of total government revenues, with the other 90 percent split between federal and municipal governments.

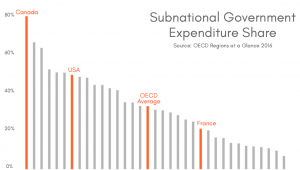

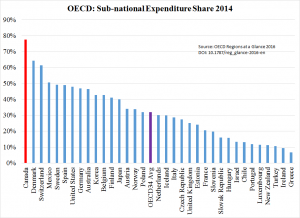

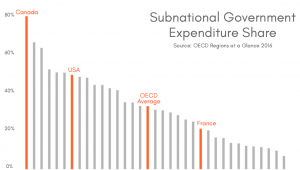

Slide 4: OECD subnational spending shares.

On this chart, you can see that by 2014, the spending share of subnational governments in Canada had risen to 78%. In the United States, it’s just 48%. The average across high-income OECD countries is 32%, and France is way down there at 21%.

This presents a mystery. How is it that we can maintain a modern welfare state mostly run by little provinces; some with only a few hundred thousand people? This looks terribly inefficient to people from any other country. How can we efficiently raise the taxes to do so? Why are we so different? Let’s now dig into this mystery to see if we can figure out how Canada can ‘get away’ with such radical decentralization that no other OECD country seems able to do.

Some argue that it is our constitution. The division of powers in the original British North America Act gave responsibility for hospitals and schooling to provinces. So, it is true the constitution provides a starting place for understanding the shape of our fiscal federation.

But, in my view, the constitution is insufficient as a complete explanation. When economic forces pushed against the constitutional division of powers, we adjusted the constitution to allow it. We did this for Unemployment Insurance in 1940 after a previous federal unemployment relief program was struck down as unconstitutional. Again in 1951 for Old Age Security, and one more time for the Canada Pension Plan in 1964.

In all of these cases, the economic argument overran the constitutional status quo. So, it can’t be just constitutional forces leading to our decentralization. Economic forces dominated constitutional ones at key points for large government spending programs in the past.

Is it our people that makes us so radical compared to any other OECD country? Do we lack a sufficiently strong sense of national economic purpose and national solidarity? I don’t know. But there are many other modern nation states on this chart cobbled together from historically independent and culturally diverse regions. Germany. Spain. Italy. Switzerland. Belgium. Are we really lacking in national solidarity compared to all of those places? One might argue that Belgium barely exists as a national cultural entity, yet their central government has a spending share twice Canada’s. So, it seems unlikely that what underlies our radical decentralization is a lack of national solidarity.

What other force shapes a federation? What about the structures of fiscal accountability? Some argue that democratic transparency and accountability demands taxes be raised at the level of government that spends them. But, in Canada, there are vast mismatches between what provincial governments spend and what they raise in taxes. PEI gets 38 percent of its total revenue from federal transfers. For Nova Scotia and New Brunswick it is 35 percent.. For BC it is 18 percent. That’s a lot of other people’s money that is spent.

Have we developed some magical and secret formula of political accountability that allows us to get away with these vast fiscal mismatches when other OECD countries can’t? I don’t think that’s true. While concerns about accountability are important to keep in mind, it’s not evident this mismatch has cost us yet. Perhaps it’s enough that provincial governments still feel at present they have enough ‘skin in the game’ to control costs.

So, we have a radically decentralized federation unlike any other in the world. I’ve argued so far that it can’t be explained easily with arguments based on our constitution, our national solidarity, or structures of political accountability. What then explains our ability to ‘get away’ with our radical federation?

Slide 5: Efficient Decentralization

In my view, it is economic efficiency that underpins the radical decentralization of our fiscal federation. We can do what we do because we found a way to do it pretty efficiently.

There are two elements.

The first is our system of intergovernmental transfers. They have constitutional origins, and are certainly held aloft by national sentiments of solidarity—as strained as those sentiments might be from time to time. Both the constitutional and solidarity arguments are important, to be sure. But to me the strongest argument for our transfer system comes from the cold logic of economic efficiency.

Let’s consider the economic argument for our transfer system.

The scope and scale for efficient production of government-provided goods varies. For some goods, like education or parks, local or provincial governments can manage the spending efficiently.

We don’t want the federal government picking the right style of park bench to put in the Public Gardens. If you’ve been watching the news, the feds don’t appear to be great at skating rinks either. Those decisions seem best made locally.

Other goods seem well-suited to the provincial level. We don’t need every town developing its own education curriculum, but different provinces have different needs and may be best-positioned to deliver the mix of education that fits their provinces’ citizens.

Moreover, provincial control over education allows for a vital ‘laboratory’ of federalism. For example, in recent years, Quebec has introduced a new math curriculum that has met with some success. Other provinces have observed this, and should be learning from Quebec’s example. So, some goods seem properly situated in the provincial sphere.

For other kind of publicly-provided goods, like transportation or environment, a national or even global viewpoint is necessary to provide government services efficiently. Federal governments can best co-ordinate spending that has impact on the national economic space.

That’s how we might divvy up the responsibilities efficiently on the spending side. Different orders of government efficiently matched to the scope of each good.

What about the taxation side?

We can do a similar exploration on the tax side of the public ledger. Which order of government is best-suited to handle different kinds of taxation?

A key consideration here is the mobility of different tax bases.

Sales and consumption taxes can vary across local jurisdictions without much economic cost. It simply costs more for most people to drive across a border to make their weekly purchases than they save in sales taxes. Now, there are exceptions. Myself, I’ve been known to make a shopping run now and again to Seattle. And I bet the folks in Amherst know which things have lower taxes across the Tantramar Marsh in Sackville and vice versa. But for the large part of consumption spending, provinces have a lot of leeway to set their own consumption tax rates without upsetting economic efficiency too sharply.

At the other end of the tax spectrum, the corporate income tax base is much more mobile. By booking costs in places with high taxes and revenue in places with low taxes, a company active across different jurisdictions can try to shift profit to where it is taxed the least. With the modern tech economy, this is made even easier, as a big company like Google can park its intellectual property in a low-tax place like Ireland and then licence the use of that technology to the high-tax places, thus siphoning the taxable income to where it is taxed least.

Similar challenges affect provincial corporate taxation in Canada. There are apportionment rules that limit the ability of companies to shift profits around in Canada, but evidence suggests it still happens.

Let’s now put this together. Imagine if we assigned spending responsibilities on the principles of economic efficiency, and then did the same for taxes. What would that look like?

Economist Albert Breton noticed 50 years ago that it would be a great coincidence if efficient spending and tax assignment resulted in balanced budgets for each order of government. Professor Breton then argued that intergovernmental grants must be in place to maintain economic efficiency.

Applied to modern Canada, Breton’s insight tells us that if we did not have a strong system of intergovernmental grants, either spending or taxation in Canada would be set inefficiently. Our system of intergovernmental grants is not there to foil or frustrate efficiency. We have intergovernmental grants to maintain economic efficiency.

So, the efficiency of our system of intergovernmental grants is one big factor in explaining the mystery of our radically-decentralized fiscal federation.

The second main factor is our system of tax collection agreements. For GST; for corporate and for personal taxes, most provinces allow the federal government to collect taxes on their behalf. The provinces have scope to choose rates and some degree of exemptions, but it is the federal government that does the actual collecting and the administration. Provinces just have to cash the cheques they receive from Ottawa.

This arrangement allows decentralized decisions about the level and type of taxes. It aligns spending with taxes to the degree possible, which bolsters fiscal clarity and accountability. It saves private taxpayers money by creating a national economic space with comparable rules and administration, rather than a balkanized system that is hard to comply with. Finally, it saves money by avoiding the replication of a separate tax administration apparatus in every province and territory. Our system of central tax administration but provincial tax rate setting is efficient, and contributes to our ability to sustain a radical fiscal federation.

So, what is the resolution to the great mystery of Canada’s radically-decentralized fiscal federation? I don’t think it is the constitution. Neither are we an outlier in national solidarity, nor in political structures for fiscal accountability.

I’ve argued here that we have been able to operate a radically-decentralized fiscal federation because we have found an economically efficient way to do so.

3. Trouble Ahead

This is the country that my grandparents and my parents’ generations have delivered to us as we sit here in 2017. There have certainly been some bumps and bruises along the way, but arguably we’ve been passed a working federation.

That’s where we are.

Where will our fiscal federation be 50 years from now, in our bicentennial year of 2067?

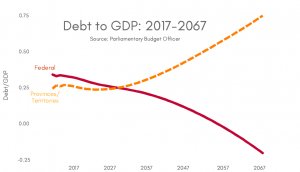

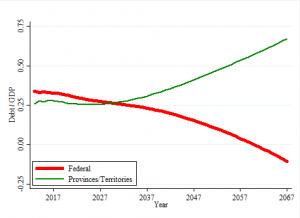

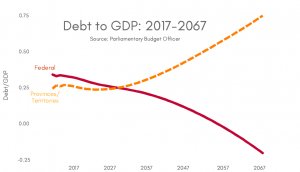

Slide 6: PBO projections

The Parliamentary Budget Officer produces an annual projection of fiscal sustainability for the federal and the provincial governments.

The chart shows the projected path of the debt to GDP ratio over the next fifty years. The federal government on its current trajectory will fully pay off its net debt by 2060. Federal government program spending and transfers to children, the unemployed, and the elderly aren’t projected to be a long-run problem. Old age pensions for the baby boom generation should hit its peak in 2031 and decline thereafter. The federal government is in a sustainable fiscal position.

The provinces, on the other hand, are not. The PBO projects debt to increase starting in the mid-2020s and the follow an explosive path. The reason is well-known: health spending.

As a caveat, there have been at least two decades of economists warning that health costs would “soon” rise substantially and some have noticed that dog hasn’t really yet barked. The Canadian Institute for Health Information reports that the annual real increase over the five years from 2010-2014 was negative 0.2%.

Provinces have been working hard at implementing innovations to the delivery and management of health services. In some places like British Columbia, there have been innovations on the structure of public-sector wage settlements. Other places like Ontario have experimented with the delivery of core services. I’m sure the government of Nova Scotia has made efforts as well.

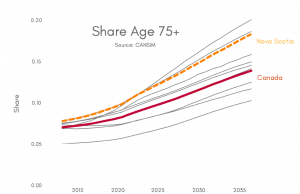

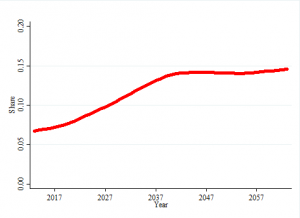

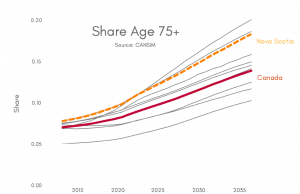

Slide 7: Age 75+ across the country.

But, the problem is about to start accelerating. Health spending rises substantially at older ages—especially after age 75. The average health spending on 40 year olds is $2,400 per year. For 75 year olds it is $11,600. Five times as much.

The 75+ population share starts to rise in the 2020s and by the 2040s will be double the current share nationally. In some places, it will almost triple. These are demographic realities fixed into our population structure and they are unlikely to vary much.

Slide 8: LucilleBall.gif

Again, provinces may be able to innovate their way through this. Economists have made bad projections before, and maybe we will be wrong this time too. But this time may really be different—the pace of demographic change is picking up and innovative health reforms will need to step up the pace substantially in order to keep up with the pace of demographic change.

To my mind, the most likely case is that provincial budgets will be strained over the next twenty years.

To take the example of Nova Scotia, the C.D. Howe Institute projects health spending will increase by four percentage points of GDP in the next 15 years. As a reference point, HST revenue in Nova Scotia is about 4.2% of GDP. So, you’d have to double the provincial part of the HST to raise enough revenue, taking the rate up to 25%. And that’s just the next 15 years. It gets worse after that.

Now, the Parliamentary Budget Office also does provincial projections, and their projections are milder than the C.D Howe ones. The PBO says Nova Scotia health spending will only rise 2 points of GDP in the next fifteen years. But that’s still a substantial challenge that can’t be ignored.

To summarize, the numbers look scary. This problem also looks unavoidable. Is there a solution?

4. An Economic Framework

Slide 9: A framework: Musgrave, Oates, Milligan & Smart

To figure out a way forward for our fiscal federation requires a framework. Let’s put together a framework starting with the work of Richard Musgrave.

In 1959, Harvard economist Richard Musgrave published a path-breaking textbook The Theory of Public Finance. This book transformed the field from what resembled more a branch of accounting featuring ad hoc principles and rules toward a field built systematically on the foundations of modern economic theory. One of his contributions was to consider the economic underpinnings of federations, and how we ought to assign taxes to different levels of government.

We’ve seen his argument earlier in the lecture, when we grappled with the mismatch between the efficient assignment of spending responsibilities and the efficient assignment of tax responsibilities across orders of government in a federation. |The thinking on efficient assignment of taxation is straight out of Professor Musgrave’s writings.

The key consideration for efficiency is the mobility of the tax base. I argued earlier that the sales tax base can be efficiently handled locally, while corporate taxes are more mobile and might best be handled centrally.

But we need to add to Musgrave’s analysis the framework of economist Wallace Oates, from his 1972 book Fiscal Federalism. Oates argues that central governments are good at things requiring co-ordination across subnational boundaries—when decisions in one place affect people in other places. But Oates also recognizes the advantages of subnational governments. Subnational governments can account for local circumstances much better than a far-away central government.

So, the Oates model rests on a tension between these two factors. Central governments are better at co-ordinating when decisions in one place affect people in other places, but subnational governments can account for local circumstances.

In a recent research paper I’ve written with Michael Smart, we combine the frameworks of Musgrave and Oates to reconsider tax assignment in a federation, with particular attention to personal income taxation.

We start with the Musgrave argument—that mobile factors are likely best taxed centrally. In previous work, we have examined the case of high income earners. We have shown that taxation of high-earners at the provincial level seems fairly inefficient, as taxpayers have some ability to respond to higher provincial taxation by shifting income to lower-taxed provinces through mechanisms like family trusts resident in a low-tax province.

But in our new research we add an Oatesian perspective. Provinces have vastly different situations. In some places, the income distribution is highly skewed with a large proportion of earnings going to the highest earners. In other places, the distribution of income is less skewed. When considering high-income taxation, it seems efficient to have different taxation of high-income people in different provinces, depending on the shape of the income distribution in different places.

Our theoretical model grapples with this tradeoff. Central government income taxation can limit cross-province income shifting while provincial income taxation can address local situations. Our main result: the best way is to share responsibility for income taxation between the federal and provincial governments.

This economic framework delivers clear guidance on how we might assign taxation efficiently in our Canadian federation. Let’s now turn to some policy solutions.

5. Radical solutions

Slide 10: Get radical Canada!

Let’s recap where we stand.

We have a radical federation. We are facing a large and daunting problem. I think we need some radical solutions. I think we’re up for it—our parents built this radical federation, it’s up to us to keep pushing it forward. We can do this.

Slide 11: Solutions

I will consider three options, taking into account the arguments and framework developed in this lecture.

First is simply to continue the status quo. The status quo does involve the Canada Health Transfer and Equalization transfers, but on the current trajectory these federal transfer programs are not going to be sufficient to fund the large-scale increase in health spending brought about by population aging. So, the status quo means provinces will be left on their own to raise substantial new funds, starting a few short years from now.

The problem with this solution is the ability of provincial governments to raise new taxes. The provinces where the aging and health problems are most acute—places like Nova Scotia—already have the highest personal taxes, the highest corporate taxes, and the highest sales taxes. How can these provinces raise substantially more revenue—on the order of 3 or 4 percent of GDP just 15 years from now—in a federation with mobile factors? I think this is a poor solution.

The next option is to federalize the coming health costs. Using Musgrave’s logic on the mobility of tax bases, the federal government is best equipped to levy taxes on mobile factors that can balance the need for efficient tax sources with the desire for fairness in the tax system where high earners pay an appropriate share of the tax burden.

This option would certainly require a major rethinking and change of mindset about the level of federal taxes. By the late 2030s, we’d need something on the order of six more points on the GST or a 40% increase of federal personal income taxes.

But, the coming wave of health spending means we do need to rethink our fiscal federation, so we can’t be deterred by whether it is a hard thing to do. We do need to be radical. Instead, the right question is whether we can do better than this option.

I see two weaknesses with the approach of federalizing health spending.

First, is fiscal accountability. I argued earlier that Canada likely does not have any special advantage in fiscal accountability over other countries, but the efficient transfer system we have built has handled the federal-provincial fiscal mismatch adequately so far. That said, I do have concerns how far this can be pushed. If provincial health ministries are funded only by cashing cheques written in Ottawa, I begin to wonder whether attention to proper cost control will be maintained.

Second is the efficiency of the tax assignment mix. Yes, it is true that the Musgravian logic assigns taxation of mobile factors to the federal government. However, my work with Michael Smart points out that the local circumstances need to be considered for efficiency as well.

So, I think we can do better for efficiency than to further centralize the tax decisions in Ottawa while leaving spending decisions in provincial capitals.

Here’s my third option: we flip the table on the current assignment of taxes, guided by our efficient economic framework. Currently, provincial governments raise about $26 billion in corporate taxes. Corporate income is relatively mobile.

Why not hand over taxation of corporate income to the federal government? In exchange, the federal government could shrink the federal GST, handing over the GST tax room to the provinces. On an approximately revenue neutral basis, this swap would cost 4 out of the 5 current federal GST points.

Then, as funding needs grow in the decades to come, provinces can raise their HST rates as required by their provincial needs.

The final piece of this proposal is the maintenance of a robust and strong equalization grant, so that provinces without large resource revenues can maintain their relative position within the federation.

So, this is a three-part plan. One, provinces vacate corporate taxation. Two, the federal government vacates the GST space—but continues the efficient central collection through the CRA. Three, maintain a robust equalization grant.

Let me lay out five advantages of this plan, and then close by addressing some weaknesses.

The first advantage is efficient assignment based on the Musgrave principle of tax base mobility. The sales tax base is not mobile, and can stay provincial. The corporate tax base is mobile, and therefore should be taxed centrally.

The second advantage is the continued shared responsibility for the personal income tax. As my work with Michael Smart shows, allowing the personal income tax to reflect provincial circumstances can be efficient. Importantly, the provincial income tax is an important tool for fairness. It will be needed to adjust the overall sharing of the tax burden generated by higher GST rates in the provinces.

The third advantage is efficient administration. Canada’s system of tax collection agreements would continue, with the federal government setting the structure for the GST and personal income taxes while provinces set the rates.

The fourth advantage is ensuring adequate fiscal accountability. If a province doesn’t pay enough attention to continuous innovation in the efficient delivery of health services, voters in that province will notice that higher GST rates that would be required.

The fifth advantage is the volatility of incomes. Corporate income tax is a very volatile source whereas sales tax is much more stable. Health spending does not vary substantially through the business cycle, so it makes sense to match that spending with a stable financing source.

Of course, this reform would not be easy. While the revenue implications of swapping corporate taxes for GST might be made to balance overall, some provinces might gain and others lose in such a swap. On precedent, Quebec may refuse to participate in such a swap. Finally, provinces facing a particularly large increase in the elderly population share may still find it difficult to raise their HST rates substantially higher than other provinces.

I don’t argue this would be easy. But I do think it is necessary. Our radical federation needs a radical solution to meet the needs of Canada’s next 50 years. Funding for future health spending increases in Canada should come from provincially-set but federally-collected GST increases, tempered by continued sharing of the personal income tax base to adjust for local conditions and for tax fairness.

6, Conclusion

To wrap up, I began by showing that Canada’s fiscal federation is radically decentralized from an international perspective. I argued that there is a strong economic foundation for our radical federation, but that we may soon face a tremendous challenge because of provincial responsibility for health spending.

I proposed a radical reform of tax responsibility, with the federal government taking over all corporate taxation in exchange for provincial control over GST revenues. Future health costs can be covered through provincial sales tax increases, balanced by income tax adjustments and a robust equalization transfer.

We’ve inherited a strong Canada from those who’ve built it. It will take some work, but we can pass a stable and thriving federation on to the next generation.

Thank you.