Background notes prepared for private corporation tax event: “Taxing Small Corporations: Increasing Fairness or Undermining Growth?”

University of Calgary School of Public Policy

September 14, 2017

Kevin Milligan, UBC Vancouver School of Economics, kevin.milligan@ubc.ca

PDF of these comments available here.

Introduction

Other speakers have covered the details of the proposed reform package in detail, so I will just summarize it briefly. The proposed package contains three measures.

- Cutting back on the ability of business owners to “sprinkle” income to other family members.

- Imposing heavier taxes on passive portfolio investments inside a corporation.

- Changes to surplus-stripping rules.

The complete details are available from the Department of Finance.

In my time here, I’m going to make three substantive arguments about the goals of the tax reform, and assess this private corporation policy package as a whole.

The three substantive points are about efficiency, entrepreneurs, and equity.

Efficiency and Neutrality

The core aim of the reform is to restore neutrality to those conducting business inside vs outside a corporation. It’s worth spending some time to understand why this is important.

At the core of the economic model of taxation, we use as a benchmark the activities people would undertake if there were no government and no taxes. When we introduce taxes to the model, we compare what people do to what they would’ve done in the absence of taxes. The choices made without taxes are our ultimate benchmark.

The ideal for a tax system is neutrality. Neutrality means people choose the same activities with or without taxes. In other words, a neutral tax system is one where the government isn’t pushing economic activity one way or the other; a neutral tax system has the lightest possible touch of government on the economy. That’s the goal.

This concept of neutrality is central to the motivation for the current reform package. To apply this concept, we don’t want to give tax advantages to those who run their business as a corporation compared to those who run their business as unincorporated, or to those who save inside versus outside a corporation.

The reform aims to pull back on the tax advantage of incorporation. Incorporation is appropriate in many business circumstances, but the incorporation decision should be made on the business merits, not because of tax incentives. We as a society don’t have incorporation because we want people to give people tax advantages. We don’t have incorporation as a back-door way to give family-based taxation to a subset of Canadians. We don’t have incorporation to provide a parking place to put your retirement portfolio. You can argue that family taxation and retirement savings are good things, but that’s not what a corporation is for. The role of a corporation is to facilitate productive investment to grow the economy and produce better jobs.

Productive investment should be the focus, not loading tax savings into one particular way of organizing a business.

This is the basic efficiency case for a reform that moves toward neutrality.

Entrepreneurs

The future of our economy is built by investment decisions made today; our future prosperity is determined by the accumulated impact of each one of those investments. We want new ideas, new firms, and new jobs to be grown right here in Canada, and the job of policy is to make sure that happens.

Is there a case for helping small business? Ted Mallet, the economist for the Canadian Federation of Independent Business argues there is.[1] He provides some good examples:

- Large firms have economies of scale in dealing with government regulations.

- Internationally active firms can lower cost of capital through international tax arbitrage.

While I think Mallet makes a good economic case for helping out small business, it’s not clear to me the existing Small Business Deduction (SBD) is the right way to do this.[2] The SBD targets small firms; we want a system that targets new and growing firms.

If our goal is helping entrepreneurs, one attractive option put forward by Chen and Mintz introduces a system where every firm can immediately expense a certain amount annually, rather than deferring the depreciation deductions.[3] This gives an advantage to smaller firms, and the advantage is directly targeted where we want it: incentives to grow investment.

While it is useful to think about bigger potential reforms, we also must address the reform package currently on the table.

Do the three tax measures currently on the table spur entrepreneurship? Are these measures effective subsidies for what we want to achieve?

The ability to sprinkle income does not reward those with good ideas. Sprinkling is not a reward for innovation, investment, or job growth. Sprinkling rewards those with a certain family structure. As for passive portfolio income, by its literal and legal definition it is the opposite of active investment in firm activities. We want productive investment in firms; we want to encourage entrepreneurial activities. It is very hard to see the link between income sprinkling and passive portfolio taxation and innovation and entrepreneurship.

I think the government can and should do more to encourage entrepreneurship and growth through the levers of the tax system. We have much better ways to encourage entrepreneurs than income sprinkling and subsidizing passive investment.

Equity

A major consideration for the politics of taxation—and the economics of taxation—is to figure out who is affected by these tax measures.

These tax measures strongly and obviously impact high earners much more than anyone else. But before I get to the facts, let me start with three caveats.

- The compliance burden of some measures may hit many regular small businesses. I hope to hear some creative ideas about how to lower the compliance burden of achieving the reform’s goals. But ultimately, the final package has to take into account whether any additional compliance burden is justifiable.

- Poorly written draft legislation might rope in too many regular small businesses. I hope Finance is listening and offers fixes to problems that have been raised.

- You can construct special cases showing someone as low as $70,000 per year might have a small impact. We should take note, but not generalize from these special cases.

In my view, these reforms have their largest impact on high earners.

First, take the case of income sprinkling. The gain to shifting income across taxpayers within a family is driven by the difference in tax rates. If the main operator of the business is in a middle tax bracket, the gain to splitting income is quite small. As the gap in the tax rate between the main operator and the other family members grows, the gain from sprinkling income grows.

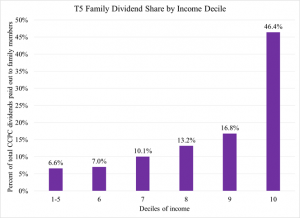

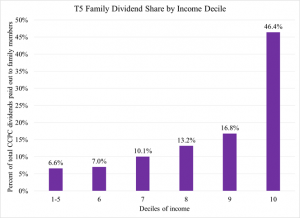

The data on dividends provided by Michael Wolfson and Scott Legree makes this very clear.[4] If you put Canadians into ten decile bins and observe who is paying out dividends to family members, only about 6 percent is paid out from the bottom 5 deciles in total. In contrast, the top decile of income is the source for 46 percent of total dividends paid out to family members. Note that this is an understatement of the ultimate tax impact, since the actual tax dollars would be even more skewed than the income shown in this analysis. The tax dollars are more skewed because the tax gain to income splitting is much bigger for higher earners for a given dollar of income since the gap between their tax bracket and the dividend recipient’s bracket is on average larger.

Source: Wolfson and Legree (2015)

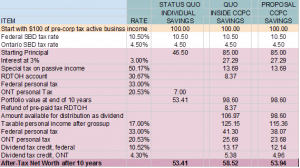

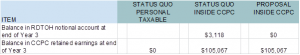

Second, let’s look at the taxation of passive portfolios. All working Canadians have access to the Registered Retirement Savings Plan / Registered Pension Plan / Tax-Free Savings Account system. If you’re a small business owner looking to save for retirement, in most circumstances you can do as well and likely better in an RRSP or TFSA than saving inside a private corporation.[5] So, the people for whom a private corporation starts to make sense are those who have more savings than can fit in the regular RRSP/RPP/TFSA system.

Of note, RRSP room for 2017 is $26,010 which covers earnings up to $144,500 if one contributes the maximum of 18 percent of earnings. Moreover, in 2015 23.1 million Canadians had a total of $909 billion in carried-forward RRSP contribution room, meaning they had RRSP space available.[6]

As a final consideration, the special tax rate that applies to passive income inside a corporation is a flat rate set to approximate the top tax bracket outside a corporation. For 2017 in Alberta this special rate is 50.67%. Since it is a flat rate, people in middle or lower tax brackets see an advantage for saving outside a corporation compared to high-bracket investors. This is the current situation.

So, while I am aware of no public data on the distribution of the $26 billion of passive investment income from CCPCs, it would be very surprising if many low or middle earners are currently making use of what is for them an expensive and tax-inefficient location for their savings.

To sum up, it is possible to construct a case that middle earners could bear some financial impact of these reforms. But the evidence and logic is quite clear that the impact of the proposed private corporation tax reform will fall most heavily on higher earners.

The path forward

To put a framework on this analysis, I propose separating policy advice into two piles.

The first pile is the “fantasy tax reform” pile. These are ideas that are outside the current political constraints.

Some examples:

- We should have a big-bang tax reform (Carter 2.0).

- We should just get rid of SBD.

- We should lower top tax rates substantially.

- We should have the family as the tax unit.

As academics and policy thinkers, it is our job to think outside current political constraints, so I welcome those offering and defending bold ideas of how we can do things differently. This is vital; that is why we sit in our “ivory towers”; to think things people in the hot house of every-day politics don’t dare to think in a particular moment.

The second pile of policy advice is to evaluate what’s on the table now. What is actually possible given current political constraints?

For this kind of policy advice, we need to compare any policy package not against the “fantasy reform” alternative, but against the status quo. Does a reform package improve us compared to doing nothing?

While offering “fantasy policy reform” advice is useful, we can’t hide from analyzing what is on the table now and comparing it not to an ideal, but the status quo.

So let me use this framework to analyze the current policy.

Does this reform meet my own personal fantasy tax reform checklist? Not really. I can see the benefit of a big “Carter 2.0” tax commission that plans our system on a rational basis for the 21st century. I think the existing small business deduction should be replaced with something better targeted at new and growing firms. The Finance package of reforms is clearly a patch on an imperfect and messy existing system.

But to the 2nd question, does this reform improve on the status quo? I think this reforms heads us in the right direction, on both efficiency and equity grounds. To merit full support, I think it is feasible and necessary to expect the Minister of Finance to address the following items when the final package is put together following the consultation period.

- Administrative burden; e.g. easier accounting for ‘connectedness’ for Mom and Pop shops.

- Problems with the draft legislation: Lots of examples have been floated that may lead to bad tax outcomes. Are these examples correct? Can they be fixed with better legislation?

- Solid and feasible plan for transition: can the passive income reform legislation meet the goal without too much complexity?

- Do more for entrepreneurs and startups. Turn the new revenue around within the small business envelope. If the Minister is serious about encouraging entrepreneurs, show it.

[1] Ted Mallet (2015), “Policy Forum: Mountains and Molehills—Effects of the Small Business Deduction,” Canadian Tax Journal, Vol. 63, No. 3, pp. 691-704. [link]

[2] The Mirrlees Review in the UK argued that there may be a case for using fiscal tools to help small business, but those tools should be targeted at the source of the market failure rather than a broad-based rate cut. See Claire Crawford and Judith Freedman (2010), “Small Business Taxation,” in Stuart Adam, Tim Besley, Richard Blundell, Stephen Bond, Robert Chote, Malcolm Gammie, Paul Johnson, Gareth Myles, and James M. Poterba (eds.) Dimensions of Tax Design. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [link] Also, the recommendations of the Mirrlees Review can be found in James Mirrlees, Stuart Adam, Tim Besley, Richard Blundell, Stephen Bond, Robert Chote, Malcolm Gammie, Paul Johnson, Gareth Myles, and James M. Poterba (2011), “Small Business Taxation,” Tax by Design. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [link]

[3] Duanjie Chen and Jack Mintz (2011), “Small Business Taxation: Revamping Incentives to Encourage Growth,” School of Public Policy Research Papers, Vol. 4, Issue 7. [link]

[4] Michael Wolfson and Scott Legree (2015), “Policy Forum: Private Companies, Professionals, and Income Splitting—Recent Canadian Experience,” Canadian Tax Journal, Vol. 63, No. 3, pp. 717-738. [link]

[5] I worked out a specific case in calculations available through my UBC blog here. Financial planning expert Jamie Golombek works through some more sophisticated cases here. Of course, individual circumstances vary so universal statements about the tax efficiency of different investment strategies are difficult.

[6] See CANSIM table 111-0040. There were 26.4 million taxfilers in 2015. Some of the 3.3 million (representing 12.4% of the total) without carryforward room were ineligible to contribute (for example someone over age 71), while others had used up all their available room.