Below is the text of a lunch talk I presented to the Ottawa Economics Association on January 27, 2016 in Ottawa.

The slides for the talk are available here.

————————————————

Budget preview

Ottawa Economics Association

January 27, 2016

Chateau Laurier, Ottawa

Thank you very much for the invitation to speak to this group.

I’m Kevin Milligan from UBC’s Vancouver School of Economics—in the picture is our fancy new building.

I was asked to prepare a budget preview, and that’s what I’ve done for you. Instead of going in depth on a couple items, I’m going to attempt more of a ‘buffet’ approach with smaller servings of a larger number of topics.

I’m also going to try to do this within the allotted 25 minutes so we’ll have lots of time for questions—so let’s get right into it.

First, let’s have a look at three current issues we know are part of the current budget discussions.

Canada Pension Plan

The chart shows the public pension replacement rate, which is the combined CPP-OAS-GIS pension total divided by average earnings. This is based on joint work with Tammy Schirle.

CPP currently replaces 25% of earnings up to a cap set at median earnings. This YMPE cap for 2016 is $54,900. OAS pays a flat monthly cheque of $570, and GIS tops up the incomes of the bottom 1/3 of seniors.

Taken together, people under $30,000 of earnings replace more than 75% of their work-life earnings, even if they don’t save a dime when working and their workplace has no pension.

Even around median earnings, more than 50% of worklife earnings are replaced by existing CPP/OAS/GIS. It’s only when you get north of $50K of lifetime earnings when the public pensions alone start doing a noticeably poor job of replacing earnings for those without other sources of retirement income.

A CPP reform would do some combination of two things. First, it might increase the replacement rate above 25%. Second, it might increase the YMPE cap above the current $54,900.

The chart shows the resulting replacement rate under the status quo and two alternatives. The ‘PEI’ option was developed in 2013 by then-PEI Finance Minister Wes Sheridan, featuring three different CPP replacement rates over three different earnings ranges.

The ‘double YMPE’ option keeps the 25% CPP replacement rate and simply extends the YMPE cap to around $100,000. This is much simpler than the PEI proposal.

What I see in that graph is that the simple ‘double YMPE’ proposal delivers replacement rates indistinguishable from the more complex PEI proposal.

Prospects for reform of the Canada Pension Plan are strong. With favourable governments in Alberta and Ontario, meeting the 2/3rd population + 2/3rd provinces is a real possibility.

After their December meeting, the Finance ministers hinted they would take this route by considering a boost to the YMPE to $75,000. I think that’s a wise direction for reform.

To be decided are two big items: First what to do about those with comparable workplace plans? Are they allowed to opt-out of the new CPP tranche? Second, whether to allow provinces to move ahead with their own more ambitious plans, like the case of Ontario.

One last note about the calendar: If the federal government and 7 provinces approve of a reform by December 31, 2016, a reform would take effect on January 1st, 2019—before the next election.

PIT changes

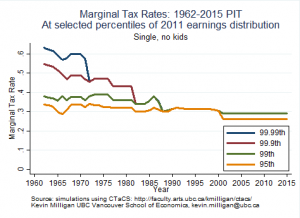

The Liberal election platform contained a number of tax policy changes. At the top of the list is the ‘Middle-class tax cut’ and the new 33% federal bracket for the top 1% of earners.

But there are several items we should hear more about in the budget.

- Timing and final configuration of the Canada Child Benefit.

- Eliminating 110(1)(d) preferred treatment of stock options.

- Tightening rules around small business CCPC taxation.

- Review of $100B in tax expenditures.

I think all four of these items are sound in principle, but the details are very important to get right. I’d be happy to talk about any of these during question period.

The fiscal item receiving the most attention has been estimates of the revenue gain from the high-income tax bracket. Let me offer some thoughts on this matter.

When considering taxing the highest income individuals, it is prudent to adjust for the reality that high-income individuals have some ability to shift income out of the PIT tax base in response to higher rates. This often occurs through financial and accounting transactions that shift income away from domestic taxation.

How much revenue would potentially be lost with the new 33% tax bracket because of tax avoidance?

In their platform document, the Liberals estimated the new tax bracket would take in $2.8 billion, and that allowed for $600 million to account for some possible tax avoidance leakage.

Alexandre Laurin from CD Howe Institute looked at the numbers and suggests that the new bracket will bring in only $1 billion.

The PBO has recently come out with an estimate of $1.8B, while the Department of Finance in December came in at $2B.

Who’s right here?

Based on my research in this area, I think the PBO and Finance numbers look closer to the mark, with one big caveat.

The PBO and Finance numbers are for a ‘business as usual case’. By that I mean they take the rest of the current tax system as a given.

In my view, the higher platform revenue number can be achieved, but only if the budget begins to take very seriously the shutting down of the avenues of tax avoidance. That takes some tax policy deftness, but also requires a large serving of ‘political will’ to pick fights with those who will be affected by the tax measures.

I’ll be looking closely at the budget for actions reflecting a serious response to tax avoidance.

Stimulus for a weak economy

The best measure economists have for the sustainability of public finances is the debt to GDP ratio. As recently as December, the Prime Minister reiterated the commitment to keep the debt to GDP ratio declining “every year”. Let’s dig into the numbers and see what that commitment entails.

Because debt-to-GDP is calculated in nominal terms, we need to have a projection of nominal GDP going forward. Fortunately, TD Economics publishes a quarterly GDP deflator projection, so I combined those with the published 2015Q3 GDP numbers to project nominal GDP forward for the 2016-17 fiscal year.

Before the numbers, some caveats.

- 2015Q3 GDP could be revised, either way.

- Real GDP and GDP deflator projections might need updating from December’s TD projection.

Keeping that in mind, I calculate that the maximum deficit consistent with a non-declining debt-to-GDP ratio is about $22B for 2016-17.

More interesting is the sensitivity of this number to the underlying growth assumptions.

If nominal growth gets pegged down 100bps, not only will the government need to project lower revenues but their ‘allowable deficit’ will also shrink down to $15B. That’s a double-whammy.

Given this, will the budget be able to credibly project a declining debt-to-GDP ratio? In my view, if the deficit starts going north of $20B, it will take increasingly aggressive GDP growth assumptions to deliver on the commitment.

In other words, if the government wants to heed the calls from some quarters of an immediate large injection of an extra $10B or $20B on top of their existing plan, they will need to bust through their debt-to-GDP commitment.

Should they? I’m not a macro-economist, so I have more questions than answers on the matter of fiscal stimulus. I have two big questions.

First, I want to be convinced that a big fiscal stimulus can be effective. Can it hit the right people in the right industries at the right time? Moreover, the case for fiscal policy can be questioned in a small open economy with inflation targeting.

Second, even if it were effective, is a big general macro stimulus the right response to a regional commodity price shock? A slowdown in the rate of national GDP growth by a point or so doesn’t seem like the kind of emergency where you would want to open the spigots on $10s of billions of unplanned emergency spending.

That said, the case for some action is justified. The oil-province economies have certainly had a tough shock delivered to them, and some transitional and targeted action should be taken. For example, for already-planned and ready-to-go infrastructure it doesn’t seem harmful to me to get the cheques out the door quickly.

Three New Items

Now I’d like to turn to three items that are not currently on the agenda, but I think should be over the next few years.

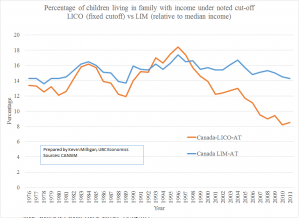

The goal of these items is use the tax system for what it should do: both encourage economic growth, and also ensure the benefits of growth are felt across the income distribution.

PIT reform

First on my list is reform of the Personal Income Tax system. The PIT as at the heart of our tax system for two reasons.

First, it is the revenue workhorse, raising about half of the $300B of federal government revenues. Second, it is the sole major revenue tool that is redistributive.

In my view, our tax system needs to be—at the very least—proportional. By proportional, I mean that the percent tax burden on everyone is the same. We don’t want a situation in which high earners are paying a lower proportion of taxes than middle earners.

Now, many Canadians might desire a system that goes beyond proportionality to one that is truly progressive. But I think the concept of proportionality is one that likely receives broad support as a bare minimum.

Here’s the thing: because the other major revenue-raisers are regressive, if you want the overall tax system to be at least proportional, you need the PIT system to be progressive. This isn’t about being a radical Robin Hood—a progressive PIT is necessary even to meet the minimum baseline of overall fiscal proportionality.

What should be the goal of any PIT reform?

I think two things are critical. First is to set out a clear purpose for the PIT—and I just gave my view on what I think that purpose ought to be.

But the reason a strong and explicitly stated purpose is important is that it gives some structure to what has become a big mess, with attempts to use the PIT as the tool to meet a wide variety of social and economic goals—not to mention short-run political goals.

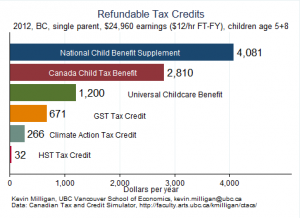

This feeds into the second criticism: the system is too complex. The tax system has been larded with a large variety of special tax expenditures, exemptions, and preferences. Moreover, the narrowly-defined PIT system interacts with our system of refundable tax credits in subtle but important ways.

This complexity matters for two reasons.

First, the complexity obscures the tax incentives that clever policy analysts designed to meet various social goals. When these incentives are stacked on top of each other, the incentives are not going to be seen by every-day taxpayers.

Second, we know from evidence on the Children’s Fitness Tax Credit that high income families are much more likely to claim the credit than middle income families. This means that, in practice, complexity comes with a side-dish of redistribution towards high earners.

As a way forward, I’ve found very attractive an idea that Robin Boadway has pushed a few times. The idea is to consolidate our existing refundable and non-refundable tax credits into a simpler more transparent refundable tax credit. Wayne Simpson and Harvey Stevens have a useful Calgary School of Public Policy Research Paper on this last year that is worth a look.

Income and Consumption taxes

The conventional wisdom from economists is that we should switch from income taxation to consumption taxation. This conventional wisdom is well-expressed in the quotation. I don’t mean to pick on Clark and Devries—as most of you know, they are both fine economists—but their consensus sentiment is oft-repeated.

I’ve become increasingly skeptical of this conventional wisdom over the past few years.

The underlying logic of the conventional wisdom is sound. We economists all know the famous Irving Fisher diagram from our undergraduate studies, and its more advanced Euler-equation analogue from our graduate studies.

But, we’re in a world right now with interest rates close to zero. Moreover, given the availability of RRSPs, RPPs, tax-free housing, and now TFSAs, who exactly is facing taxation on the marginal dollar of saving? Here’s the answer: almost no one.

So, while I accept the underlying logic of the income-vs-consumption economists, I want to see clear evidence that the tax wedge that concerns them is actually something that matters in Canada in 2016.

If we’re going to undertake a contentious reform, I’m not willing to proceed on faith–I want to see clear Canadian numbers on what the gain to reform would be.

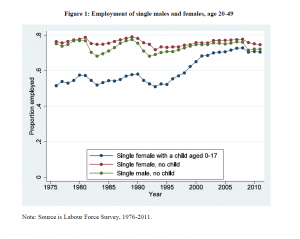

Improve the WITB

The last item on my ‘to-do’ list is the Working Income Tax Benefit. The WITB provides a boost to earnings for those who are looking to join the workforce in the manner you can see in the chart. This benefit does not go out like other refundable tax credits as monthly or quarterly cheques. Instead, it is embedded within the standard tax form.

There is strong evidence from a number of countries that these kinds of ‘in work’ benefits improve employment rates, and the extra dollars improve the lives of parents and kids.

But, in my view, the current WITB suffers from two shortcomings.

First, it is too meagre. If you are a minimum wage full time full year worker, your annual earnings would be about $20K. But, a single worker earning $20K gets no WITB. To me, an effective WITB would target the exact kind of worker I described, so the existing configuration falls short.

Second, because it is delivered through the tax system, buried in the middle of the complex tax form, it lacks salience. How many Canadians actually know this benefit exist and plan their work year around it? If I were designing a tax benefit to be the least salient possible, it would look pretty similar to today’s WITB.

To fix these problems, WITB needs to be expanded—which will cost more money. But its structure needs to be changed as well to improve salience. I have some ideas how to do that—but I’ll save those for another time.

Two ‘little bites’

To finish off, I have two ‘little bites’ to offer.

Last year I wrote a review of the tax system in Nova Scotia. At the time of writing, Nova Scotia had the highest personal tax rate, the highest corporate tax rate, and the highest HST rate in Canada. How is Nova Scotia supposed to raise taxes on its own to finance current and future spending needs—especially when the working age population has been in absolute decline since 2006?

Finally, continued strong corporate investment is pivotal for our future prosperity. Corporate taxes are neither the only nor the most important determinant of corporate investment, but they do matter. I’m not sure we need to do more on corporate tax rates in Canada, but I think efforts to design better structure of corporate taxation are worth attention. Proposals from Robin Boadway and Jean-Francois Tremblay from Mowat, as well as Ben Dachis from C.D. Howe have pushed in the direction of rent taxation systems. These systems would have a material impact on the incentive to invest, and I hope we see more research in that direction.

That’s it—thanks for your attention and I look forward to your questions.