Inclusive Corporate Tax Reform

by kevinmil

Inclusive Corporate Tax Reform

Kevin Milligan

Vancouver School of Economics

University of British Columbia

Notes prepared for Northern Policy Institute “State of the North” conference

September 26, 2018

North Bay, ON

Powerpoint slides here.

PDF of notes here.

Why do we have corporations? Why does society have corporations? What is their function; the benefit they give us?

We don’t have corporations to provide tax shelters for the rich.

We don’t have corporations to act as a cash cow for the government.

We don’t have corporations to employ lawyers, nor accountants, nor tax collectors.

Now, some of these things may be side-products of the way corporations work in today’s society, but none of these things is at the core of why corporations exist.

A main reason we have corporations, at the core, is to facilitate productive investment in the future capacity of our economy.

We want to ensure a vibrant and flourishing economy for our children. To reach that goal, we need investment in the productive capacity of our economy.

Now, when we have ample investment, that’s clearly good for business owners. More investment means more economic activity, more profit, and more GDP.

In principle, more investment is also good for workers. In a competitive and well-functioning labour market, we expect workers get higher pay when they have access to the best machines, equipment, tools, and software.

As investment grows, GDP is going to grow. And we might hope we’ll see wages growing too.

But over the last generation, this fundamental economic relationship has fundamentally failed to deliver for average workers in Ontario.

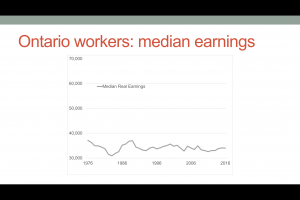

CANSIM Table 11-10-0239-01, median employment income

In this chart, I show median inflation-adjusted employment earnings for Ontario workers. If you line up everyone with employment income and pick the person in the middle of the lineup, that’s what I’m graphing here. This is the earnings for the typical Ontario worker.

There’s no cherry-picking of the data here. If you separate out men and women, you’d see women growing a bit and men shrinking a bit. If you look at full-time full-year workers, the story is pretty much the same.

For forty years, employment earnings has barely moved in Ontario.

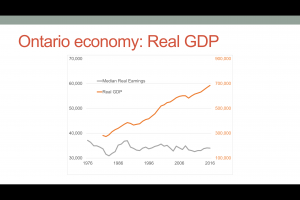

GDP data: Table: 36-10-0222-01 (formerly CANSIM 384-0038)

If you now plot Ontario’s GDP in the same figure, you can see that the economy has more than doubled in size over this period.

The economy has doubled in size, but the typical worker is not getting any further ahead.

What’s going on?

Economists have been studying this stagnation of earnings around the world, looking at factors like the pace of technological change, shifts in trade patterns, the slide in unionization, and a decrease of employee bargaining power. The exact reason for the stagnation isn’t the focus of my talk here today.

The point I want to draw out here is simply this: in a global economy that’s throwing tough challenges at Canadian workers, the very last thing we want to do is to make it hard for Canadian firms to invest in their companies, their future, and their workers.

We need that investment to boost our companies and our economy; to give us a fighting chance against the global trends pushing down on Canadian workers.

On this front, our tax system plays a role. The environment for investment depends in part on how we tax the return to investment by corporations.

But if you’re a typical worker and you look at this chart, you might find it hard to get energized for reforming corporate taxes if all that happens is GDP goes up without any boost for average workers.

You may be wondering why we should care what median-earning workers think about corporate tax reform and economic growth.

I think everyone should care, and here’s why.

There are many Canadians who care a lot about inequality: what’s happening to those who are struggling economically, and also those in the middle of the pack.

Many understand that some people through no fault of their own are held back from reaching their potential. Factors like discrimination, lost schooling opportunities, and plain bad luck can keep many people from achieving their highest potential.

For people who focus a lot on inequality, you can naturally see how they might want to understand how corporate tax reform affects everyone in the economy.

But not everyone thinks about inequality in the same way. Our economy works best when hard work is rewarded, and some part of the inequality of economic rewards may reflect inequality in economic effort.

That’s fine—people have different views about inequality. I can tell you I know some people who don’t care at all about inequality. They think Robin Hood belongs in fairy tale books, socialists belong in Venezuela, and every person should eat only what he or she can kill.

But I think these folks—even the ‘eat what you kill’ capitalists—should care about the overall impact of a pro-growth corporate tax reform too.

The reason is that in a democracy, if you don’t keep your growth policy focused on middle workers, then you’re not going to get a chance to implement your policy. You’re just not going to get much support for reforms if people in the middle feel they’re left out.

Again, just look at the chart. Some people argue that if a tax reform increases GDP, we can just let the rest sort itself out.

Forty years of experience in Ontario says that’s not enough anymore.

If your argument for a corporate tax reform is that it boosts GDP and you ignore everything else, many Canadians will respond that this isn’t enough anymore.

We do need investment. We do need growth. And we do need to improve our tax system as part of that effort. But how?

How do we construct a policy of tax reform that has a better shot at helping all workers?

Here’s what I think: we need to embrace Inclusive Corporate Tax Reform. There are two elements to Inclusive Corporate Tax Reform.

The first is to keep the focus on investment. Remember, the reason we have corporations is to facilitate productive investment in the capacity of our economy.

It just makes sense to align our tax system with the core reason we have corporations in the first place: investment.

Investment at the centre of corporate tax reform means that we focus less on rewarding profits from past investments, and emphasize tax benefits for investing more for the future.

Investment at the centre of corporate tax reform means we work hard to shut down tax planning structures that waste energy and talent on accounting tricks, and refocus that energy on delivering efficient investment in productive capacity.

Workers know that a company that is growing and investing in its future will provide the best shot for the workers to thrive in the future too.

Restoring investment to the centre of the tax system is the best way to align our tax system with what we want corporations to do for our economy.

The first element of Inclusive Corporate Tax Reform is investment.

The second is to be sure to include everyone.

If we cut the tax burden on the corporate sector, that revenue will need to be made up somewhere else.

An inclusive approach to corporate tax reform doesn’t ignore this need to fund the tax cuts; instead the need to fund the tax cuts is embraced.

This means paying attention to who pays how much tax, and ensuring that the tax reform doesn’t tilt the system to put more burden on the people in the middle.

You can make tax reform inclusive by enforcing existing rules on tax avoidance and tax evasion, while simplifying and tightening administration.

You can make tax reform inclusive by adjusting the tax system to ensure that the progressivity of the tax system—the tax balance between rich and poor—isn’t thrown askew by any tax reform.

An Inclusive Corporate Tax Reform pays attention to ‘who pays what’ in our tax system, so that everyone can be included and have a stake in the success of our economy.

These are the two elements of an Inclusive Corporate Tax Reform. Investment, and including everyone.

In my view, we should assess potential corporate tax reforms against these two criteria because looking at GDP alone simply isn’t enough anymore.

But what kind of policies fit the bill? Here are a few ideas.

Right now, when a company invests, the investment is written off over many years, so the tax benefit is spread out.

With full expensing, the tax benefit is front-loaded. This kind of structure can maximize the boost given by our tax system to investment.

But how would we make up the revenue? Here are two ideas.

We could increase the capital gains inclusion rate from today’s 50% to 2/3rds. Right now, the capital gains rate is out of whack with how dividends are taxed, giving too much of a break for the liquidation of corporate cash into corporate stock buybacks. By restoring the balance of capital gains with dividend taxation, we can remove this mis-incentive and also raise more revenue.

Another idea is to revisit the full exemption of capital gains on housing. In other countries like the US, the capital gains exemption for the principal residence is capped. In Canada, it is completely uncapped, creating a major tax loophole for those with millions of dollars to speculate on housing. Canada should look at capping this tax loophole.

Now, maybe you don’t like these ideas. That’s fine—I won’t push these particular ideas too hard here today.

But what I do ask you to consider is the idea of Inclusive Corporate Tax Reform and putting investment and inclusivity at the centre of our tax reform discussion.

Too many tax reform proposals anchor their arguments in boosts to GDP. If you want a reform that is better for all Canadians—and also has a better chance of becoming law—I think we need to take Inclusive Tax Reform seriously.

Thank you!