Energy, Equity, and Social Struggle in the Transition to a Post-Petrol World

The relationships between energy and society are multifaceted and highly complex. Energy issues, be they intra/international conflicts, peak oil, or the viability of renewables, are central not only to geopolitics of empire and climate change, but also to the most banal reproduction of everyday life. International awareness of the challenges faced by climate change and fossil-fuel dependency has given impetus to a widespread reevaluation and critique of industrial society’s relationship to energy. This paper surveys some of the key tensions between various critiques of the energy/society relationship, and highlights the importance of equity, labour, and livelihood in relation to discussions of energy futures. Furthermore, this paper explores whether a shift to “alternative” energy requires an accompanying new mode of production and social relationship to capitalism.

PDF of Energy, Equity, and Social Struggle in the Transition to a Post-Petrol World

December 20, 2010 No Comments

speed-stunned imaginations: a reflection on Energy and Equity (CR #3)

In his recent book Hot, Flat, and Crowded: Why We Need a Green Revolution—And How It Can Renew America, New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman declared that we have entered the “energy climate” era. According to Friedman’s narrative, the solution to the twin crisis of peak oil and climate change relies overwhelmingly on technical advances and market innovations. Along with his win-win scenarios for business and the environment, Friedman states, “Only if we got abundant, cheap, clean reliable electrons could we deal with climate change, petro-dictatorship, biodiversity loss, energy poverty, and energy resource supply and demand. That is the cure” (Shea, 2008). While Friedman’s holds out for such an invention to come and solve the world’s socio-environmental problems, I think it is apt to revisit Ivan Illich’s 1973 essay Energy and Equity, where he posits there are social limits to the ever-expanding consumption of energy, renewable or otherwise.

Illich states “The widespread belief that clean and abundant energy is the panacea for social ills is due to a political fallacy, according to which equity and energy consumption can be indefinitely correlated” (2). Using the example of the transportation industry, Illich attests that energy and equity can grow concurrently only to a point. Above a certain quantifiable threshold, energy and equity are negatively correlated (Illich, 3). Writing in a period in which the automobile had become the utmost priority in transportation planning and urban design, Illich saw the endorsement of speedier and more energy-intensive modes of transport as involving the homogenization of landscapes and the annihilation of “commons into unlimited thoroughfares … for the production of passenger miles” (18). This new round of space-time compression was manifested physically in an accelerated rate of land-take for transport infrastructure. For example, in Los Angeles during the 1960s, over one third of the downtown became exclusively parking lots (excluding the spaces of traffic corridors), producing an environment where every citizen found the autonomy and use-value of their feet reduced (Coolidge, 2007).

Crucially for Illich, this unevenness is the outcome of transportation, as an industry, dictating the configuration of social space and incorporating class inequality in its material structure. Across North American cities, personal automobile ownership came to be a prerequisite for participation in social life and work, for the spatial dispersion of the post-WWII urban form made “the consumption of the products of the auto, oil, rubber, and construction industries a necessity rather than a luxury” (Harvey, 39). In this light, the prized personal mobility bought by having an automobile was in fact involuntary traffic made necessary by the settlement patterns that cars create. While transportation is an insignificant cost for upper-class speed capitalists, the necessary infrastructure for unlimited high-speed travel dictates that the majority spends larger amounts of personal time on unwanted trips (and larger amounts of labour time to earn the money needed to commute to work). Across cities, the result is “more hours of compulsory consumption of high doses of energy, packaged and unequally distributed by the transportation industry” (Illich, 8).

Illich’s insights are applicable not only at the urban scale, but also at the scale of core/periphery in world systems theory. As John Whitelegg notes in his study on transportation policy, the majority of World Bank loans for transport spending from 1962 to 1994 were geared towards new highways, rail closure and privatization (1997;54). Whitelegg recommends that if the World Bank “has the ultimate objective of reducing poverty … then they could ensure that 95 percent of investment funds are not steered in the direction of 5 percent of the population who are in a position to drive themselves around and carry freight by truck (1997;58). The massive subsidies and policy preference for increasing energy-intensive, private forms of transport comes with highly uneven benefits, not to mention increased dependency on industrially-packaged forms of energy.

A second parallel can be drawn between Illich’s work and that of Arghiri Emmanuel, who helped develop dependency theory and its arguments of unequal exchange and declining terms of trade for “developing” countries. Emmanuel showed that “low-wage countries have to export greater volumes of products in exchange for a given volume of imports from high-wage countries than they would if the wage level were uniform” (Hornberg, 7). The low-income transit user who must spend the largest proportion of income on mobility is akin to the developing country that must spend higher shares of their export incomes on the importation of energy. Renewable energy advocate and late German politician Hermann Scheer researched this “energy trap” by comparing the ratio of export incomes of African countries to the costs of importing oil. Scheer found that the costs as a percentage of import spending incurred by importing energy have risen from 5-10% in the 1960s to upwards of 80% (2009, B III). Furthermore, “In 2005, the developing countries’ oil import costs rose by 100 billion dollars; this is significantly more than the sum of development assistance provided by all the industrial nations put together” (2009, B III). Participation in the Global North’s model of global trade (and its necessary infrastructure for industrialized transport) comes with high costs to equity and compromises other development goals.

When considering whether renewable energy will offer new possibilities for emancipation from a crisis-prone system, it is crucial to keep in mind the possibility that abundant, renewable energy may only perpetuate, perhaps even strengthen, forms of hierarchy and domination in the sunbelts and wind-corridors of the world. Thinking beyond the renewable/nonrenewable binary, “All industrial energy systems deploy space, capital, and technology to construct their geographies of power and inscribe their technological order as a mode of organization of social, economic, and political relations” (Ghosn,7). In his anticipation of a future beyond oil, Friedman dismisses the continuities between conventional and alternative energy and overlooks the deep structural issues having to do with power, control, and unequal access to resources. The attractiveness of ‘renewable energy’ as a panacea for social and environmental ills, independent of a wider social transformation of capitalism, risks foreclosing serious political questions about alternative socio-environmental trajectories.

Works Cited

- Coolidge, Matthew. “Pavement Paradise: American Parking Space” Center for Land Use Interpretation 2007.

- Ghosn, Rania. “Energy as a Spatial Project” New Geographies vol (3) 2009 pg 7-10, Cambridge; Harvard University Press.

- Harvey, David. The condition of postmodernity: an enquiry into the origins of cultural change. Cambridge, Massachusetts : Blackwell, 1989.

- Hornberg, Alf. “The Unequal Exchange of Time and Space: Toward a Non-Normative Ecological Theory of Exploitation” in Journal of Ecological Anthropology vol (7) 2003 pg 4-10

- Illich, Ivan. “Energy and Equity” in Toward a History of Needs. New York: Pantheon, 1978

- Friedman, Thomas. Hot, flat, and crowded; why we need a green revolution—and how it can renew America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008.

- Scheer, Hermann. “Renewable energies and the environment”, Committee on the Environment, Agriculture and Local and Regional Affairs. Council of Europe 18 May 2009

- Shea, Danny. “Tom Friedman Calls For Green Revolution”. Huffington Post. 4 July 2008,

- Whitelegg, John. Critical Mass: Transportation, Environment and Society in the Twenty-first Century, Pluto Press: London 1997.

November 28, 2010 1 Comment

Communication Difficulties- Denying, Astroturfing and Teabagging (CR #2)

I have noticed a recurrent theme throughout all of our discussions thus far; communication is central. How do we effectively communicate the values and ideas inseparable from our visions for a hopeful future beyond the triumphant, end-of-history discourse of the neoliberal growth machine? As Saul Alinsky wrote in Rules for Radicals, no progressive movement can succeed without the broad-based support of the middle-classes, the dominant constituent of the North American population. And indeed, many of our discussions seem to be derailed as soon as one of us asks “how realistic is to expect the [insert stereotype of SUV driving, overweight North American here] … to understand and change their lifestyle?” Alinsky noted that the middle-classes are a difficult bunch to organize with mass change in mind, for they have just enough economic security to stave off the desperation which usually coincides with unrelenting and passionate movements for change in a capitalist system dominated by short-term economic interest. In this response I would like to outline some of the defining communication issues that pervade the interconnected debates around energy and climate change, specifically in the US political landscape.

In considering the very important question of how to effectively communicate the possibilities for alternative systems (steady-state economies being one), I would rather spotlight some of recent, alarming tactics used by those out to convince the public that there is in fact no reason to seek out, debate, and initiate alternatives. This is evident in the strategies to delegitimize the international consensus on climate-science and undermine the transition to renewable energy used by the shared forces of free-market capitalists, oil barons, and right-wing ideologues.

The first tactic, used primarily by right-wing political strategists, has been to co-opt a wide range of theories associated with the “post-positivist left” about scientific uncertainty (Wyly, 315). Frank Lutz, a well known Republican strategist, advised Bush and others to deploy the “lack of scientific certainty” as the primary issue when deflecting calls to adopt GHG-emission targets (Wyly, 311). Bruno Latour, a pioneer in the philosophy of science, reacted to this strategy in the following way,

“Entire Ph.D. programs are still running to make sure that good American kids are learning the hard way that facts are made up, that there is no such thing as natural, unmediated, unbiased access to truth, that we always speak from a particular standpoint, and so on, while dangerous extremists are using the very same argument of social construction to destroy hard-won evidence that could save our lives” (Wyly, 312).

What was born as a radical critique of the power structures embedded in industrialized practices of science, popularized by thinkers such as Michel Foucault and Donna Haraway, has now become the ammunition with which power strengthens its will to ignorance.

The second tactic has been the appropriation of organizing strategies emanating from Alinksy and other 1960s era radicals. Rules for Radicals has even been assigned as bed time reading for the Tea-Partiers across the US. Alinsky’s manifesto was born out of his experiences organizing marginalized populations across the US to take back power from elites. However, the Tea-partiers are not simply a grassroots collection of ‘have-nots’ seeking power from the ‘haves’; the movement has little to say about marginalization, exclusion, or inequality. Rather, many linkages have been drawn financial and organizational support coming from, among others, oil companies.

This brings me to the third tactic, astroturfing; the attempt to artificially produce what on the surface looks like a grass-roots movement.

This New York Times article, among others, links the finances of the Koch Industries (today’s equivalent of Standard Oil) to Americans for Prosperity, a key organizing force of the Tea Party Movement.

Not only does the movement stand for further neoliberalization, tea partiers also have an agenda to halt progress on federal legislation regarding climate-change mitigation. It should come as no surprise that Koch Industries has significant economic stakes in seeing no slow-down of the Alberta’s tar sands given their ownership of pipeline and refinery facilities across America. The Koch Industries’ astro-turfing is not limited to the protection of the oil-industry’s profits. The Koch Family is noted for providing the start-up funds for the Cato Institute in 1977 which “consistently pushed for corporate tax cuts, reductions in social services, and laissez-faire environmental policies”, and continue to donate to “nonprofit groups that criticize environmental regulation and support lower taxes for industry”. The NY Times article reads,

“When President Obama, in a 2008 speech, described the science on global warming as “beyond dispute,” the Cato Institute took out a full-page ad in the Times to contradict him. Cato’s resident scholars have relentlessly criticized political attempts to stop global warming as expensive, ineffective, and unnecessary. Ed Crane, the Cato Institute’s founder and president, told me that “global-warming theories give the government more control of the economy.””

If our group is to critically interrogate the collective imagination of energy, we must speak truth to power, and recognize there is nothing natural about our relationship with energy and the practices which reproduce the conditions for “crisis”. Rather, our practices are highly political, and the tactics outlined above attest to the traditional energy sectors influence on not only our present political agendas, but also on the vocabulary with which to imagine future alternatives.

Since the 1960s, Shell has practiced what is called scenario planning, or the act of telling stories about possible future events in order to strategize effectively. The acronym “TINA” (There is No Alternative) has come to organize all of their scenarios since the 1990s and represents to them the triumph of globalization and liberalization. The massive capital already invested by Shell and other companies in existing infrastructure makes it near impossible for them to envision their own proactive role in a future beyond oil, even if they may be cognizant of peak-oil and climate change. Rather than aid the transition, members of the traditional energy sector wield their political influence to distort the public discourse on climate change.

Although the tactics described above are at the extreme end of the spectrum and most prevalent in the US, they nonetheless give insight into the ways in which discourses are shot through with power. How the middle classes are communicated to and how they vote will play a central role in an energy-mode shift. What we should realize is that these dirtiest of tactics are having real consequences, with the overwhelming majority of congressional republicans who ran in the midterm elections all sharing a denial of climate change.

While this response does not give a positive answer to the question of ‘how realistic it is to ask people to change’, it details some of the mechanisms used to foreclose the possibility that these questions may even be seriously considered. Knowing is have the battle right?

Works Cited:

Alinsky, Saul Rules for Radicals: A practical primer for realistic radicals, New York, Random House 1971

Wyly, Elvin “Strategic Positivism” in The Professional Geographer, 61(3) 2009

November 15, 2010 No Comments

R.I.P. Hermann Scheer: Author of Energy Autonomy

Long-term German politician and renewable energy advocate, Hermann Scheer, passed away last Thursday. He was one of the primary voices featured in the movie Energy Autonomy, and indeed, wrote a book by the same name, envisioning a transition to distributed, decentralized energy production.

Some of the main ideas I took away from the movie:

There has been a worldwide decoupling of energy production from energy consumption. The idea of energy autonomy is to re-localize energy production with networked systems of wind, solar, and bio-gas. This can be a strong poverty-reduction strategy in rural areas, and developing countries as a whole, especially when the costs of importing energy into a country is proportionately high to its overall GDP.

From Hermann Scheer’s perspective, the transition to renewable energy cannot be delegated to the traditional energy sector, whose main priority is maintaining the status quo of their previously built infrastructure. For Scheer, Carbon-Capture and Storage (CCS) is a “bad investment” and is characteristic of the clinging, death grip that the traditional energy sector has on fossil fuels. The energy transition must instead be advanced by a mass movement of people who start integrating renewables and smart design into the way they use transit, build their homes, and power their appliances.

A few criticisms of the movie:

Overwhelming emphasis on technological innovations and entrepreneurs, with little to no mention at all of capitalism (its need for growth/mass consumption)

There was no hint of “overshoot”, or our collective footprint exceeding the carrying capacity of the earth, and thus, the requirement of reducing consumption and material throughput.

Problematic endorsement of electric (sport)cars.

And lastly, the idea of autonomy could have been taken a bit further as there was no connections made to the political possibilities of a world where citizens have direct control of their energy supplies.

Otherwise, an uplifting movie, perhaps one of the first about energy to paint an optimistic vision of the future! (that is, if you aren’t counting this:

October 16, 2010 No Comments

The Crisis of the Fossil-Fuel Mode of Production: Critical Response1

The system of global capitalism is approaching limits to growth. Most clearly poised for transformation is the underlying energetic basis of the economic system, fossil fuels. In this response I will briefly historicize the integral nature of fossil fuels to the contemporary form of capitalism and seek to understand the ways in which capitalism is coping with limits to its energetic basis.

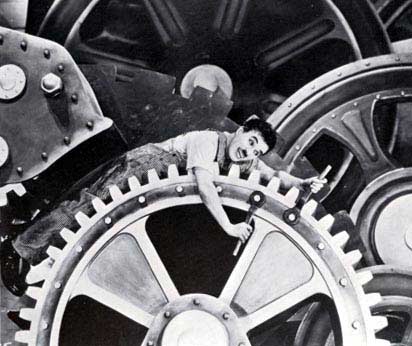

Historically, fossil fuels played a critical role in the spread of capitalist relations. Fossil fuels, particularly oil, are an extremely concentrated source of energy and a geographically mobile source of energy. These flexible properties forever changed capitalism’s productive forces, and its means of circulating (transporting) commodities. Matthew Huber notes that prior to the industrial revolution, roughly 85% of all mechanical energy came from animal and human muscle power, the rest coming from wind and water (107). The industrial revolution freed production from numerous physical (land/bodies) and temporal constraints. The intensity with which fossil fuels could be used did not change through the progression of the day, or the passing of the seasons. Steamboats, railcars and later, automobiles, circumvented the barriers to markets that long-distance travel represented, thereby increasing the sphere of commodity relations to a world scale. For the first time ever, the core energetic base of the production process was no longer human power, but rather an inanimate resource Gavin Bridge termed “geological subsidies to the present day, a transfer of geological space and time that has underpinned the compression of time and space in modernity” (48). The social relationship to capitalism also transformed; workers become more and more like a “living appendage of the machine” (Huber, 109).

Since the Industrial revolution, inexpensive fossil fuels have been normalized and internalized as necessary conditions for production and circulation. The spatial conditions necessary to sustain such a system are so prevalent (cars, trucks, highways, airports ect.) as to become nearly invisible and largely taken-for-granted. The vast claims on spaces made by this infrastructure are critical to globalization and the most successful and important logistical innovation for industry today, “Just-In-Time Production”. This mode of production fully harnesses the logic of cheap, space-annihilating transport for the following reasons: “very low coast of transport as a proportion of total costs; and the very large savings that can be made by manufacturers who use long-distance sourcing and inter-plant transfers to benefit from wage rate differentials, economies of scale, and variations in grants and subsidies to manufacturers who claim, and appear, to be creating jobs by moving them around” (Whitelegg, 67).

However, this historically specific “fossil-fuel mode of production” is poised for a dramatic upheaval in the face of peak-oil. While many speak of a looming energy-crisis in terms of a collapse or confrontation with “scarcity”, it could be reasonably argued that capitalism is experiencing the “energy crisis” in an all together different way. As James O’Conner notes, “Limits to growth … do not appear, in the first instance, as absolute shortages of labor-power, raw materials, clean water and air, and urban space, and the like, but as high-cost labor-power, resources, and infrastructure and space” (1998, 243). As the easy-to-recover oil reserves become few and far between, oil companies are exploring ways to overcome the expensive limitations to profit that deep-sea oil, Arctic oil, and tar sands reserves represent. In this sense, the peak-oil crisis is not about running out of absolute reserves of oil, but instead is a confrontation with the loss of the massive subsidy that cheap oil represents and the falling rate of profit this entails. The traditional neoclassical economic model assumes that growth is only constrained by demand (O’Conner, 1998, 243). However, when the costs of labor, nature, infrastructure and space increase, capitalism must restructure or experience crisis. To avoid crisis, the oil industry’s strategy has been twofold; (1) rely on technology development to make uncooperative oil reserves like the tar sands profitable, and (2) build infrastructure such as pipelines thousands of kilometers long to overcome the costs that vast distances represent. I think this imperative to overcome the limitations to profit is highly relevant to understanding some of the largest energy and construction projects in recent times. Both the Alaskan Oil-Pipeline and the current Tar-Sands projects in Alberta (along with the Enbridge proposal to pipeline oil across BC to China) represent the immense political and economic drive to overcome limits to growth, no matter what the spatial or thermodynamic implications.

The PBS documentary The Alaska Oil Pipeline vividly showed how the oil crisis of 1973 rationalized this controversial mega-project. After the OPEC embargo, US President Nixon signed the Trans Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act into law, disabling any further legal challenges to the project. The pipeline project mobilized near-instant work camps in the isolated Arctic terrain to work day and night on an “eight hundred mile pipeline that traversed three mountain ranges, thirty-four rivers, and eight hundred streams” (PBS). By the end of the project, 32 pipeline workers had lost their lives, and the ecosystems of Prince William Sound are still recovering from the 1989 Valdez tanker spill (PBS).

The higher the price of oil, the more incentive oil companies have to develop uncooperative reserves. However, because price is an abstracted value, or a claim-on-wealth, it cannot currently account for the thermodynamic limitations that energy-intensive resources entail. The issue of whether oil can be turned a profit is entirely mute when the amount of energy used to extract and refine oil approaches the amount of energy you recover. A true-cost accounting of the Albertan Tar-Sands project would revise the notion of profit as a clever shifting of costs onto the environment and future generations dealing with climate-change. So long as the benefactors of the traditional energy-sector hold political sway, industry will continue to rationalize its ever-expanding need for the “black gold”.

Works Cited:

- Gavin Bridge – “The Hole World: Scales and Spaces of Extraction” in New Geographies 2009, (vol 2). Harvard University Press

- James O’Conner – “Is Sustainable Capitalism Possible?” in Natural Causes (1998), Guilford Press, London

- Matthew Huber – “Energizing Historical Materialism: Fossil Fuels, Space and the Capitalist Mode of Production” Geoforum 2009 (Vol 40), Issue 1, Pg 105-115,

- John Whitelegg – Critical Mass: Transportation, Environment and Society in the Twenty-first Century (1997), Pluto Press, London.

October 9, 2010 No Comments

linguistic difficulties with 'energy'

The seminar is off to a great start, with 14 students enrolled from a diversity of backgrounds.

Our first topic of discussion dived into the history of the emergence of the collective idea of the word “energy”. Just what exactly do we mean when we say this word, so strong in connotation yet weak in denotation?

Ivan Illich’s lecture, titled “the social construction of energy”, looks back to the physicist’s role in trying to encompass into a word the concept of that which is inexhaustible and always conserved. Illich classifies this denotation of energy as the scientist’s “e”, differentiated by the popular term “energy”, which having left the defined space of the laboratory, has taken on vast connotations. Illich takes issue with the way founders of mainstream classical economics have claimed a monopoly on the term ‘energy’, defining it as “nature’s ability to do work” in a world presupposed to be governed by scarcity. In such a world, appropriating energy, like work itself, is a moral duty. But Illich, imparting these warnings in the 1980s, asserts that society is headed towards a future of “an energy-obsessed low-energy society in a world that worships work but has nothing to do for people” (17). (see structural unemployment).

In discussing energy from a social and spatial perspective, I hope to engage with the subtle, yet crucial, characteristics of our energy extraction, production and consumption that are often left out in mainstream discussions of energy issues. In regards to oil, when industry experts and spokespeople use the impoverished language of “efficiency” and prices per barrel as their primary indicators for discussing the future direction of the resource’s use, what other aspects are omitted? How do we go about taking account of the space(s) resource networks traverse in order to make it to the pump? How can we elevate the importance of the livelihoods of those living in Iraq (among other places) within our perspective? When discussing energy issues, these omissions play a major role in how we define the scope of the problem.

For instance:

The diversity of tactics in combating climate change on the ground, whether its market-driven Carbon-Capture-Storage (CCS- pumping metric tons of carbon dioxide into the ground) or international social movements demanding climate justice and a moratorium on further fossil-fuel exploitation, speaks to the huge gulfs in how different groups go about defining the “crisis”. Is the “energy crisis” about running out of the massive subsidy of easy-to-extract oil and facing the true environmental/social costs of an industrially-packaged lifestyle, or is it about the dangerous abundance of fossil-fuels, whose rapid exploitation and combustion has pushed the climate into “crisis”, or something entirely different?

How we define the crisis creates the scope of solutions. CCS appears to be a coping strategy designed to purge fossil-fuel intensive industries of their most undesirable characteristics (carbon emissions) while preserving its fundamental nature (the insistence on the growth of a fossil-fuel based economy) and is symptomatic of a limited view of the issues at hand.

September 22, 2010 No Comments

Registration is open

Landscapes of Energy: Mon + Wed in room Geog 200 (Term 1)

Coordinator: George Rahi

The focus of this course is to examine the relationships between energy and society. Energy issues are central not only to geopolitics of empire and climate change, but also to the most banal reproduction of everyday life. Mass awareness of the challenges ahead in the face of climate change and fossil-fuel dependency has given impetus to a widespread evaluation and critique of our current relationship to energy. How have governments and individuals been able to respond to these issues within the framework of global capitalism? Does a shift to “alternative” energy require an accompanying new mode of production and social relationship to capitalism? This course will explore the social, political, and spatial impacts of the present energy mode and the implications of the next.

August 9, 2010 No Comments