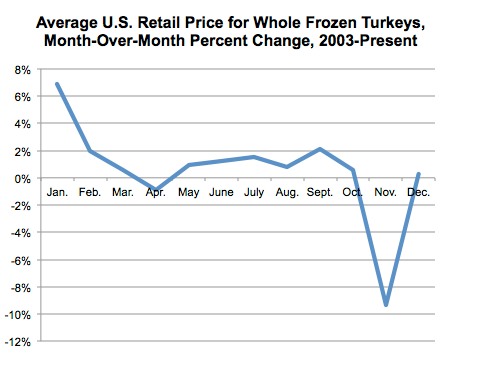

While Canadian Thanksgiving is behind us, Americans still have their turkey dinner to look forward to. In Catherine Rampell’s blog with the New York Times, she discusses the uniqueness of the pricing of turkey. Furthermore, she compares the prices of frozen turkeys across the whole year, looking into why exactly frozen turkeys are the cheapest around both Canadian and American Thanksgiving—when there’s the highest demand for turkey.

Rampell briefly touches on the pricing of fresh (not frozen) turkeys, but because they don’t have nearly as long of a shelf/storage life as frozen turkeys, pricing is nearly inelastic. For that matter, she mainly discusses the pricing of frozen turkeys.

In determining pricing of a product, we’ve learned in class that it essentially boils down to 5 main components: company objectives, customers, competition, costs, and channel members. Using what I’ve learned through marketing, I believe the competition and customer aspects of the 5 Cs of pricing are what create a dip in frozen turkey prices during Thanksgiving.

Due to the lack of differentiation between frozen turkeys from different suppliers, competition is high. Due to this high competition, prices are driven down as each firm attempts to capture the most of the turkey market. At Thanksgiving in particular, demand for turkey is substantially higher than the rest of the year, but prices still remain low.

With lower margins, suppliers of frozen turkeys then must become sales oriented: they want to maximize volume of sales. This increase in volume of sales helps to make up for the lack of profit in frozen turkeys around thanksgiving.

When looked at from a marketing perspective, the drop in prices of frozen turkeys can be explained using some of the 5 Cs of Pricing.

http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-vlfp32yhdg0/UKv-pPaynlI/AAAAAAAABog/eLFCVXe-xy8/s400/thanksgiving-jokes.jpg