My new article in Policy Options explores whether Canada can reconcile its climate policy targets with the temperature limits in the Paris Climate Agreement. The article is based on an analysis I conducted with Kirsten Zickfeld of Simon Fraser University – the report is available here.

The answer depends on how the world divides up the carbon that could be burned while keeping the planet within the temperature limits. From the report:

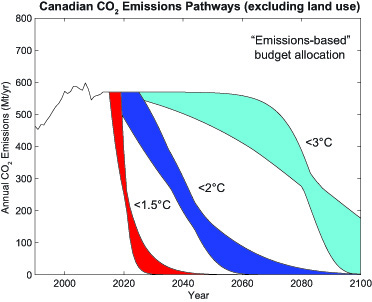

If you divide the pie based on each country’s present-day emissions, wealthy high-emitting Canada gets a generous helping for a country of its size (1.6-1.8% of the remaining carbon budget). If you divide the pie based on population, Canada gets a more equitable but much smaller slice (0.5% of the remaining budget).

With a generous helping of carbon pie, future emissions pathways for Canada that are consistent with the temperature limits would look like the figure at left. The 1.5°C limit is “at best unrealistic, at worst politically impossible.” The current Canadian target of reducing emissions by 30% below 2005 levels by 2030 could be consistent with the 2°C limit, provided emissions continue to rapidly decline after 2030.

With a generous helping of carbon pie, future emissions pathways for Canada that are consistent with the temperature limits would look like the figure at left. The 1.5°C limit is “at best unrealistic, at worst politically impossible.” The current Canadian target of reducing emissions by 30% below 2005 levels by 2030 could be consistent with the 2°C limit, provided emissions continue to rapidly decline after 2030.

Other countries, however, may not like Canada taking such a generous helping:

Allocating the remaining carbon budget based on present-day emissions places an unfair burden on developing and rapidly industrializing countries that historically have had low per-capita emissions. Despite being far less responsible for climate change to date, and currently having low per-capita emissions, countries like India would essentially be asked to bear an equal part of future mitigation efforts.

Equity, granted, is also an issue within Canada. I’ve been asked about emissions trajectories for individual provinces (that are consistent with the Paris temperature limits). Those trajectories would depend on assumptions about how Canada’s carbon budget “should” be allocated between different parts of the country. The answer for Canada as a whole is already dependent on assumptions about our slice of the global carbon pie; advancing this analysis to the provincial level would introduce even greater uncertainty, not to mention greater room for argument.

A simple approach would be to simply “scale” the emissions trajectories depicted above to the provincial emissions. Following that logic, the percent reduction targets, and the percent change in emissions by year, would be the same across all the provinces. That method, however, ignores the wide differences in mitigation potential and historic emissions burden. Perhaps the only thing that is clear from this analysis is that there’s no easy solution for Canada.