It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. The agreement reached at the U.N. climate summit (“COP21”) in Paris is truly groundbreaking and historic. At the same time, the promises made by the participating countries are not close to sufficient to avoid dangerous impacts from climate change.

To shed some light on what just transpired, I present awards for the best, worst, and most dubious achievements in the Paris climate agreement:

Best overall provision

Winner: Net emissions reaching zero

For the first time, the world’s governments from the U.S. to Tuvalu to Saudi Arabia to China have recognized that we should reduce emissions to zero by sometime in the latter half of the century. The wording is certainly clunky – “to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century” – but this is an award for overall achievement, not best screenplay.

Best source of confusion

Winner: Is the deal binding?

Runner-up: Why include targets that may be impossible to achieve?

Technically speaking, the agreement is legally binding. Article 15 establishes a “mechanism to facilitate implementation of and promote compliance.” However, that does not mean every feature of the agreement is legally binding. Compliance in this case effectively means meeting the reporting and target creation promises listed in the agreement. The emissions targets in each country’s Nationally Determined Contributions are not binding under international law.

Naturally, a lot of people are upset that the emissions targets themselves are not legally binding. Yet this is an example of politics being the art of the possible. Negotiators wanted to create a deal that all countries would accept and that their governments would ratify. Many countries would never have ratified a deal that included punishment for failing to meet their target. Without binding emissions targets, the U.S. in particular can avoid a certain-to-fail vote in the Senate on ratification (see the next award). Had the negotiators given in to pressure for binding emissions targets, the agreement most likely would have failed.

Hunter Cutting has a clear breakdown of the enforcement mechanisms on the Road Through Paris blog.

Best word

Winner: “Shall”

Runner-up: “Should”

In international legal-ise, “shall” implies a binding commitment, while “should” implies a non-binding intention. There are 141 shalls in the Paris Agreement and only 41 shoulds. The final decision on the agreement was held up for several hours because of a supposedly mistaken “shall” in the following statement:

Developed country Parties shall continue taking the lead by undertaking economy-wide absolute emission reduction targets (Article 4)

This “shall” was changed to “should” at the behest of the U.S. (through intermediaries) to ensure that emissions targets were not legally binding under international law.

Largest gap in the agreement

Winner: Ambition vs. actual emissions targets

Runner-up: Actual vs. pledged climate finance

It is well known at this point that the emissions targets volunteered by individual countries are not sufficient to meet the temperature targets in the Paris Agreement. The “ratcheting” provision in the agreement lays the groundwork for strengthening these targets. Each country is required to submit a new Nationally Determined Contribution every five years that is as, or more, ambitious than the last one:

Each Party’s successive Nationally Determined Contribution will represent a progression beyond the Party’s then current Nationally Determined Contribution and reflect its highest possible ambition (Article 4.3)

Given this provision, the current emissions reduction pledges from individual countries could be seen as the minimum reductions expected in the future. Although I am not entirely convinced by their analysis (notably the treatment of non-CO2 forcings and feedbacks), an analysis by Climate Interactive and MIT Sloan finds that improving the emissions pledges every five years could limit warming to less than 2°C.

Best (and most misunderstood) newcomer

Winner: 1.5°C temperature limit

The inclusion of a “safer defense line” of 1.5°C has received a lot of attention. Prominent scientists, like Kevin Anderson, have correctly argued that it is next to impossible to avoid more than 1.5°C of warming without widespread implementation of negative emissions technology – things that can suck CO2 out of the air.

The feasibility argument, though technically correct, misses some of the reasons why countries want temperature targets in this agreement.

The targets, especially 1.5°C, are a signal to countries like the Republic of the Marshall Islands that the world recognizes harm will come with more warming. Without mention of 1.5°C as a “safer defense line,” this would be an agreement dictated by the developed world, not a truly global deal that reflects the challenges of the whole planet. In Paris, the U.S., Europe, and a coalition of small island developing states and least developing countries successfully used the proposed language for a 1.5°C target to isolate and eventually win over rapidly industrializing countries like India and South Africa who were blocking progress on an agreement.

The temperature targets lay the groundwork for the adaptation, capacity building, and finance sections of the deal. They also ensure that if it actually becomes feasible to achieve stabilization of the climate at 1.5°C, for example via some affordable air capture technology developed decades from now, there is an international agreement in place that may compel those with access to the potential technology (likely developed countries) to take action.

Biggest disappointment

Winner: Climate finance

For all the concern about non-binding emissions targets, the finance provisions are arguably the weakest part of the deal. The parties agreed to keep the $100bn/year target for 2020, to consider higher targets in the future, to have developed countries continue to take the lead, and to seek a balance between mitigation and adaptation finance, a major concern of the developing nations. Other than the agreement to submit communications about climate finance every two years, none of the provisions are binding.

With climate finance, the devil is in the details. It is difficult to separate “climate” aid from other development aid, and to ensure that “climate” aid does not come at the expense of other initiatives. The Paris Agreement did not tackle any of the really difficult questions surrounding finance. More to come on this in later posts.

Most hollow victory

Winner: Loss and Damages

After much debate, the concept of “Loss and Damages” was elevated to equal status in the UNFCCC as the core challenges of mitigation, adaptation, and finance. There is now an entire Article (#8) in the convention about “averting, minimizing, and addressing loss and damages associated with the adverse effects of climate change.” However, the Paris Agreement basically shunted aside any chance of reparations – payment to developing nations for past, present, or future damages due to climate change. The decision document stipulates that:

Article 8 of the Agreement does not involve or provide a basis for any liability or compensation

Instead, Article 8 focuses on support and cooperation on things like early warning systems and emergency preparedness. These are very valuable but are not what developing countries envisioned when “loss and damages” was first proposed years ago.

Best new provision with an unfortunate name

Winner: Global stocktake

It may sound like a global anti-capitalist movement, a financial accounting trick, or a farm convention, but the global stocktake is a very critical part of the Paris Agreement. The Parties agreed to report every five years on their progress, not just towards their emissions targets, but towards their adaptation and climate finance targets.

Biggest break from the past

Winner: Collective responsibility

The agreement that all countries should eventually reduce emissions broke a 20-year deadlock between developed nations, known as “Annex 1” under the Kyoto Protocol and developing nations. There is still recognition of “common but differentiated responsibilities” and “respective capabilities” of different countries: the world does not expect the same targets from a major power like the U.S., a rapidly industrializing country like India, and a least developed country like Madagascar. Yet for the first time, all countries accepted that they should participate in the mitigation effort.

Most half-assed reference to something a lot of people care about

Winner: Climate justice

Despite lobbying by activists and many countries including India, the references to climate justice in the agreement in the adaptation and global stocktake were cut from the final text, leaving just this somewhat dismissive phrase in the preamble:

Noting (i) the importance of ensuring the integrity of all ecosystems, including oceans, and the protection of biodiversity, recognized by some cultures as Mother Earth, and noting the importance for some of the concept of “climate justice,” when taking action to address climate change

Most fascinating number

Winner: 55%

Runner-up: 1.5°

The Paris Agreement will enter into force once “at least 55 Parties to the Convention accounting in total for at least an estimated 55 percent of the total global greenhouse gas emissions” ratify or approve of the deal. According to 2014 data from the Global Carbon Project, China (27%) and the U.S. (16%) together represent 43% of the world’s fossil fuel emissions. If these fractions stay constant, it may be possible, albeit unlikely, for the agreement to come into force without ratification by either of the two biggest emitting countries.

Most overlooked new provision

Winner: Capacity building (Article 11)

Runner-up: Loss and Damages (Article 8)

Meeting many of the provisions in the agreement – from increasing ambition on mitigation, to managing climate finance, to implementing and reporting on adaptation plans – is challenging for many developing countries. This is especially the case in small island countries where complying with the reporting requirements of international agreements can consume all of the time of top government bureaucrats. However, this also links to the next award.

Best way to support international development consultants

Winner: National adaptation plans

Runner-up: Capacity building

Under the Paris Agreement, countries need to create national adaptation plans and “periodically” assess adaptation actions, climate impacts, areas of vulnerability, and monitoring and evaluation of adaptation. While important, this will be a boon for consultants with experience in least developed countries and small island developing states where the capacity to do such bureaucratic work is more limited.

Best word(s) I had to check in a dictionary

Tie: “mutatis” and “mutandis”

Mutatis mutandis is a Latin legal term meaning “(once) the necessary changes have been made.”

Most ironic omission

Winner: “market”

Runner-up: Green Climate Fund

The section on creating an international carbon market (Article 6) never actually mentions “market” because of opposition from countries like Bolivia to the concept of market-based mechanisms.

Most curious omission

Winner: Green Climate Fund

Runner-up: Migration

Despite being created by the UNFCCC to distribute climate finance to the developing world, the Green Climate Fund is not mentioned in the finance section of the agreement. The role of what was supposed to be a central node in the global climate finance system is now quite fuzzy. The omission likely reflects disappointment among developing countries that the initial outlays from the Green Climate Fund were loans and small grants aimed to leverage other larger investments, rather than solely public sector grants. People are asking how the Fund is different from other existing multilateral lending agencies.

Best overall performer

Winner: The United States

Runner-up: France

Like it or not, this is the deal the Obama Administration wanted: ambitious, global, but without the binding emissions and financing targets which would have ensured defeat at home.

Best “pound for pound” fighter

Winner: The Republic of the Marshall Islands

Runner-up: Bolivia

This small atoll nation and its charismatic foreign minister Tony de Brum played a central role in the “High Ambition Coalition” that broke a stalemate over language surrounding temperature targets and responsibility for emissions reductions. Think about this: an island chain home to just 60,000 people whose very existence is threatened by climate change and a place treated terribly in the past – the U.S. is still compensating the Marshallese for damages from hydrogen bomb tests in the 1950s – played a central role in getting the world to agree on a deal to address climate change. If this were a movie, you would say it was not realistic.

Final award: Best unresolved issue

Tie: Aviation and shipping

The Convention does not cover aviation or shipping, which represent roughly 8% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions and are among the fastest growing sectors. Emissions from aviation and shipping are governed by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the International Maritime Organization (IMO). There is some talk of the UNFCCC taking governance back from the ITO and IMO if they do not implement agreements of similar ambition to the Paris Agreement, but there was no mention of shipping or aviation in the agreement.

Stay tuned! The U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change will return. COP22 in Marakkech, Morocco begins on Nov 7, 2016.

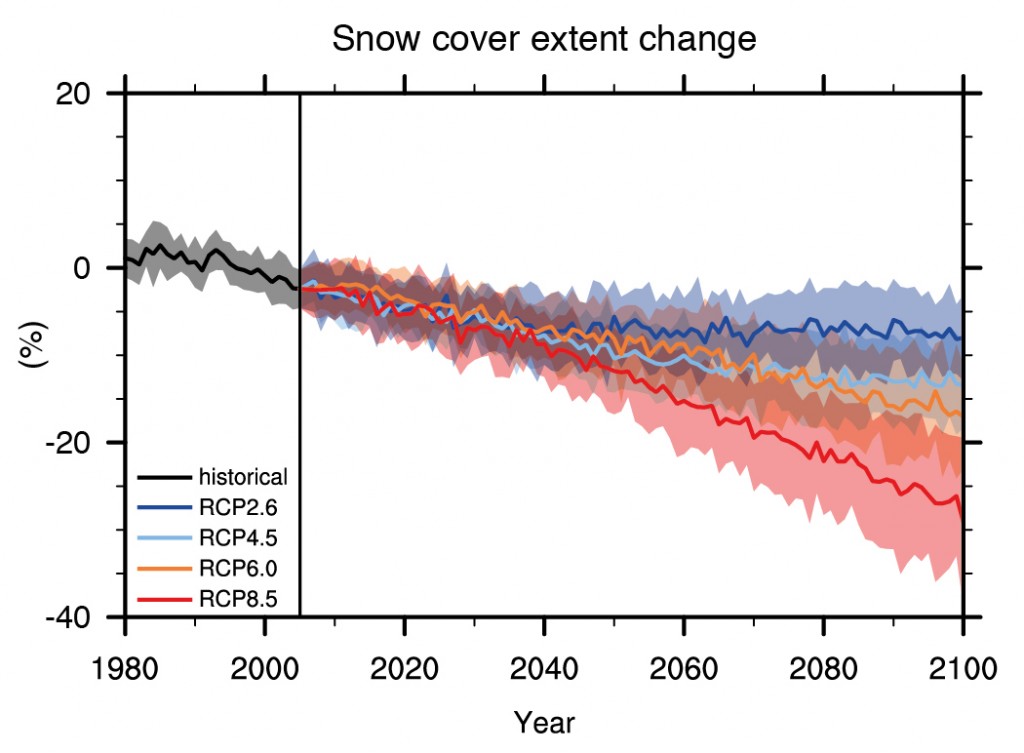

r to find snow, particularly in late winter and spring. Since the late 1960s, Northern hemisphere snow cover has decreased 1.6% per decade in March and April and 12% (!) per decade (!) in June, according to the last IPCC report.

r to find snow, particularly in late winter and spring. Since the late 1960s, Northern hemisphere snow cover has decreased 1.6% per decade in March and April and 12% (!) per decade (!) in June, according to the last IPCC report.