There is an ongoing feud about value in communicating the scientific consensus on climate change to the public. One side argues that we need to talk about the consensus in order to raise public awareness about climate change. A new review article by John Cook and Peter Jacobs (also described in the Guardian) reviews the evidence for “consensus messaging”. The counterargument, proposed by Dan Kahan and others, is that talking about consensus will increase political polarization about climate change.

A recent paper by Kahan called “Climate Science Communication and the Measurement Problem” suggests the disagreement among communications researchers is related to the “contamination of education and politics with forms of cultural status competition”. It is a fascinating paper with a lot of important findings. But I wonder if, deep in the data, there may be evidence that the drumbeat of climate change news and outreach campaigns has actually been effective.

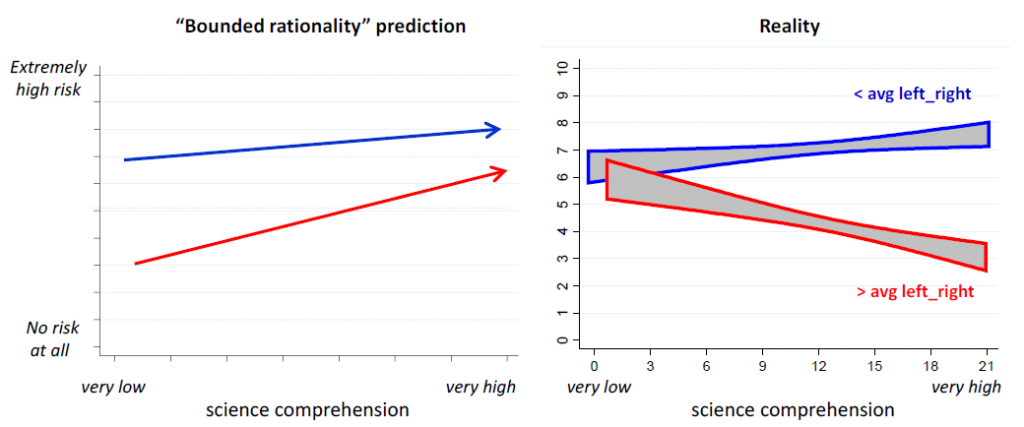

The core result of the paper is described by the following figure:

If people were rationally assessing scientific information, higher science comprehension would translate into higher perceived risk from climate change (left panel). Kahan’s experiments find the opposite for people on the right of the political spectrum (red, right panel). That’s been the headline: for conservatives, better knowledge of climate science might mean less concern about climate change.

If people were rationally assessing scientific information, higher science comprehension would translate into higher perceived risk from climate change (left panel). Kahan’s experiments find the opposite for people on the right of the political spectrum (red, right panel). That’s been the headline: for conservatives, better knowledge of climate science might mean less concern about climate change.

In other words, when people go beyond the basics, opinions become polarized. That is not very surprising, given that someone on the right of the political spectrum with greater interest and/or ability in science who looks for information about climate change may head to right-wing media and blogs, which often house an alternate universe of “facts” about climate change.

What is more surprising are the results for people with low “science comprehension”.

Why are people with low science comprehension on both the left and the right of the political spectrum perceiving moderate to high risk from climate change? If people’s views on climate change are defined more by their cultural identity than by the facts of the case, why would people on the right of the spectrum with low science comprehension have even moderate concern about climate change?

This opinion about the risk from climate change must derive from something. It isn’t a detailed knowledge of the science, or the problem. Otherwise, the people would fall elsewhere on the graph. It also isn’t their community. Their community, if defined correctly, generally believes the risk from climate change to be low.

What’s happening? Perhaps there has been enough mention of climate change in the public domain, whether on the news, in private conversations, etc., that even those who pay scant little attention to science have been able to develop some level of concern about climate change.

It may be that, current polarization aside, the much-maligned information deficit model has actually worked, at least with very basic information, and in the way political messaging works. Years of repeating the general facts of the case – climate change is real, caused by humans, and poses a risk to the future – appears to have created a basic public consciousness about climate change.

“Gaffers who claim that winters were harder when they were boys are quite right—except that the change is too small to be detected except by instruments and statistics in the hands of professional meteorologists. Weather men have no doubt that the world at least for the time being is growing warmer.”

“Gaffers who claim that winters were harder when they were boys are quite right—except that the change is too small to be detected except by instruments and statistics in the hands of professional meteorologists. Weather men have no doubt that the world at least for the time being is growing warmer.” The “ice season” on lakes and rivers all across the Northern Hemisphere has been shrinking. One of the

The “ice season” on lakes and rivers all across the Northern Hemisphere has been shrinking. One of the