Fewer than 50% of Ontarians voted in this month’s provincial election, letting the state of Canadian democracy slip to a new low. How can citizens be so quick to criticize politicians who labour far longer hours than do many Canadians, when a majority of citizens won’t even show up to cast a ballot once every several years? If you don’t like Canadian politics, look in the mirror. More and more, our critiques need to start with our individual apathy, especially in Generation X-it.

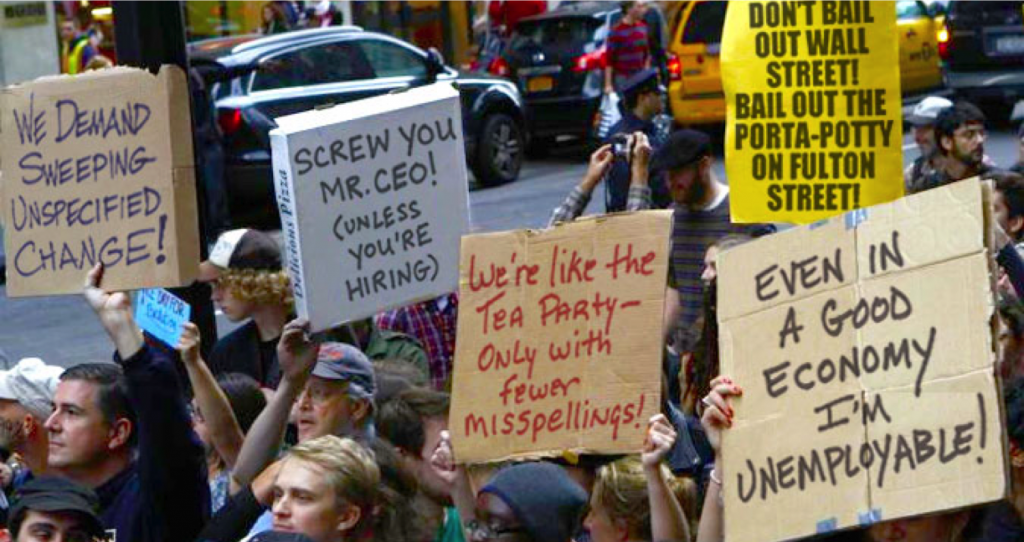

While voter turnout is dismal, Occupy Wall Street protests spread across North American cities, including in Canada this past weekend. These demonstrations give hope to democracy, even if you don’t support the message. With the general disinterest for politics in our country, we should take our hats off to any who raise their political voice in peaceful ways.

Occupy Wall Street groups have been criticized for not having a unified message, although corporate bailouts and growing inequality between the uber-rich and the rest are common themes. “We are the 99%” is a powerful slogan. Organizations as disparate as the Conference Board of Canada and the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives report that the richest 1% of Canadians make 14 percent of total income, and took home more than a third of the growth in incomes since 1998.

But here’s the problem. “We’re the 99%” frames the issue as a select few fat cats gorging themselves on cream produced by many little mice churning the milk. The story of Mouseland governed by cats is a metaphor that worked excellently for Tommy Douglas back in the day. It’s less likely to move public opinion in Canada now.

Canadians are devoted to the value of personal responsibility. There is more dignity at the end of a shovel than at the end of a handout, many of us think. People reap what they sow, and deserve what they earn. These beliefs underscore the amazing work ethic that Canadians demonstrate, ranking among the top countries for average employment hours.

One implication of a commitment to personal responsibility is that it works both ways: if you are poor, you failed; if you are rich, you earned your success. Plus, there is always the Canadian and American dream that we all can one day earn our way to super-rich status.

The fat cats focus overlooks important generational realities. The Canadian economy grew more than 100% since 1976, producing an additional $35,000 of prosperity per household ON AVERAGE after controlling for inflation. Averages are deceiving. Household incomes have stalled for the generation raising young kids as they take on massive debt to keep up with real estate prices. By contrast, those age 55-64 are doing far better: their incomes grew by nearly $12,000 compared to near-retirees in 1976, they have far more wealth because housing prices nearly doubled over their adult lives, and they leave the planet hotter than they inherited it.

Occupy Wall Street may signal a growing concern about inequity between the rich and the rest, but we can only address these pressures by tackling the intergenerational tension. The Boomer generation about to retire may be the richest our continent has ever seen, while young families struggle with a substantial decline in the standard of living. This is a bad intergenerational deal.

To be clear, it’s not about Boomer-hating. Quite the opposite: it’s about inviting Boomers as allies. Unlike fat cats who have no reason to care about struggling mice, Boomers have strong emotional ties to the generations that follow, and want their kids and grandchildren to succeed. We’re far more likely to mobilize Boomers to support a Better Deal for young families than we are to move fat cats to share cream with hungry mice.

Speaking about generations helps to ensure we don’t get distracted by the language of personal responsibility. There’s no doubt personal responsibility is a value to which all generations in this country subscribe, including those under 45 who work longer employment hours and perform more unpaid caregiving than others. But talking about generations makes us also think about historical TIMING.

Those who came of age in the 1970s did so in housing markets that were going up after they already owned homes; in labour markets where wages were on the rise, especially in return for education; and in an environment where global warming was not yet a serious constraint. Boomers didn’t earn these blessings. They lucked out in the lottery of timing. The generation raising young kids doesn’t enjoy this same good fortune, as wages are more stagnant, housing is unaffordable for many first-time buyers, and climate change occurs around us.

So Occupy Wall Street, as you evolve in Canada, here’s some unsolicited advice. Talk less about fat cats and more about Boomers who abandoned their beavers. Recall beavers adapt to changes in their environment by ensuring their dam does not leak. Not because any beaver lives in the dam, but because the dam ensures there is a reservoir on which all in the beaver community depend. If the reservoir is deep enough, beavers swim efficiently, far faster than they walk on land. If the reservoir is deep enough, beavers enjoy more security from predators. If the reservoir is deep enough, there is space for beaver families to build their lodges.

Canadian Boomers did benefit, and continue to benefit, from the policy planks that make up our national dam – the public universities, unemployment insurance, workers compensation, public pensions and public medical care. These national policies were in place before Boomers became adults. As Boomers retire, the national dam is leaking – not because the same policies don’t exist, but because the environment has changed, and we have yet to adapt our national policy dam. As the generation raising young kids tries to gain a foothold in the resulting flood, two questions become critical.

First, will the generation raising young kids find its voice, and use it to influence public policy decisions, including at election time?

Second, will Boomers help build new policy to address the growing inequality that makes many Boomers “the rich,” and many in the generations that follow, “the rest.”