Welcome to UBC Blogs. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start blogging!

Monthly Archives: February 2019

GRSJ 300: Culture Jamming Assignment – Commercial Sex Work

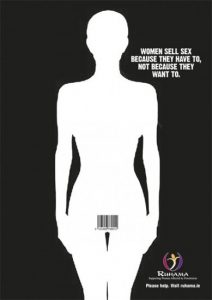

I chose this poster for the culture jamming assignment because the general idea of it has been replicated in multiple anti-prostitution campaigns. It features a silhouette of a woman of ambiguous age and ethnicity, with a barcode placed above the woman’s genitals. This clearly sends the message of the reductive nature of sex work, suggesting that in this realm, the woman’s worth is distilled down the commercialization of her body for sex. The text highlights the inherent victimhood of sex workers by this commercialization, stating, “Women sell sex because they have to, not because they want to.”

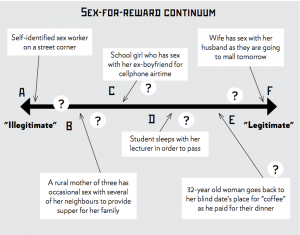

This poster is problematic for several reasons. Firstly, it promotes a highly moralistic view of sexuality as it intersects with gender in a dominant heteronormative, patriarchal, and monogamist society. These views inform perceptions of what “legitimate” and “illegitimate” sexual transactions can be, which are illustrated in the graphic below. Secondly, the poster conflates sex work and trafficking.

Sex-for-reward continuum, describing society’s perceptions around legitimate and illegitimate sexual transactions. Marlise Richter. “Sex Work as a test case for African Feminism.” BUWA! A Journal on African Women’s Experiences.

The text “Women sell sex…not because they want to” insinuates that women were coerced into selling their bodies. However, the term sex work itself highlights labour and income generation, and recognizes the consent and agency held by the sex worker. Although sex trafficking (i.e. involuntary or forced engagement in commercial sex) exists, sex work is the voluntary exchange of money or goods for sexual service – a nuance that is flattened by the poster. Lastly, the vast diversity of the nature of the sex trade and the people who engage in it is lost in the poster. Sex work is a diverse industry, with a wide variety of jobs and reasons for entry that are circumscribed by context. Some sex workers, particularly in the street-based industry, experience acute levels of marginalization that inform their decision to enter sex work – poverty, homelessness, substance use issues, mental illness, etc. However, others may find sex work to be lucrative and a job with greater benefits than others have to offer. Sex work can take many different forms, such as adult film, erotic performances, dance, peep shows, indoor, street-based, brothel/agency, independent, online, etc. Furthermore, not all sex workers are women, with men and LGBTQ+ and Two Spirit folk being key groups engaging in the trade.

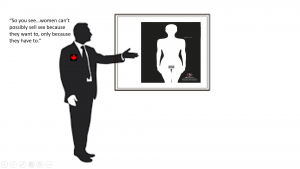

Jammed Poster:

In my jammed version of the poster, I have attempted to bring awareness to the fact that the above-mentioned dominant narratives around sex work are imposed on sex workers by the institutions that continue to oppress them. This is represented by the male government official, distinguished by the Canadian maple leaf, explaining these narratives matter-of-factually: “So you can see…women can’t possibly sell sex because they want to, only because they have to.”

I chose to portray a government official to bring awareness to how these societal narratives are translated into laws and policies which infringe on the rights, health and safety of sex workers. While sex work has never been criminalized in Canada, contradictory laws exist that ensures that it is virtually impossible to engage in sex work without breaking the law. Canada employs the Nordic or end-demand model, where clients and third parties are criminalized for 1) purchasing sex 2) communicating for the purposes of exchanging sex for money/goods 3) profiting as a third party from sexual services 4) procuring someone to provide sexual services and 5) third party advertising to provide sex services. Although the ‘target the sex buyers and pimps, not the sex worker’ rhetoric is touted as the ideal strategy to rescue the victimized prostitutes, targeting any of the parties involved in the sexual transaction with the intention of abolition has been shown to have dire impacts for sex workers. For example, recent research has shown that criminalization of customers and communication has led to rushed transactions that prevent sex workers from properly screening new clients, leading to more incidents with violent or otherwise problematic clients. Furthermore, sex workers participate in a range of work-related relationships with third parties, such as paying for protection, driving them to appointments or manage their advertising. Canada’s third-party laws thus decrease sex workers ability to work with others to maintain a safe workplace. Confusion around the laws also scare away customers, and compounded by the ban on advertising, sex workers suffer economically. In this way, it is evident that all the narratives and societal attitudes around sex work that are seen in the original poster are enshrined in our laws and continue to perpetuate an oppressive environment for sex workers – all in the name of rescuing.