When I was a child and discovered that my name, Kate Damon, spelled backwards was Nomad Etak, I developed an alter-ego in my games. Nomad Etak was me but not me, an extension of myself when I played with my sister in the wooded area behind our house. The name came to mind once again as I decided on a nom

de plume for my twitter handle and a blog name for this FNIS 401F course. While I had chosen NOMAD ETAK somewhat humorously, upon reading M arshall McLuhan’s The Medium is the Massage (1967) I began to think of my username as a nexus between online technology and the self. Similar to the way in which childhood blurs the lines between ‘reality’ and ‘imagination,’ online technology massages the relationship between the physical body and the extended self.

arshall McLuhan’s The Medium is the Massage (1967) I began to think of my username as a nexus between online technology and the self. Similar to the way in which childhood blurs the lines between ‘reality’ and ‘imagination,’ online technology massages the relationship between the physical body and the extended self.

In his seminal book, The Medium is the Massage, McLuhan argues that mediums such as print technology and electric technology shape not only messages (communication practices) but society itself. Whereas print technology gave rise to mass-production and a culture of individualism, electric technology has dispersed information on a global scale, overturning a linear understanding of time and space, and created a ‘mass-audience’ of interconnected individuals. McLuhan’s thesis is perhaps best encapsulated in the following quote:

“All media work us over completely. They are so pervasive in their personal, political, economic, aesthetic, psychological, moral, ethical and social consequences that they leave no part of us untouched, unaffected, unaltered. The medium is the massage. An understanding of social and cultural change is impossible without a knowledge of the way media works as environments.” (McLuhan, 26)

There is a physicality to this quote that I find particularly compelling. By writing that media “leave no part of us untouched, unaffected, unaltered,” McLuhan evocatively moves from the macro consequences of new technologies on society as a whole to the micro changes that impact the individual body. The subsequent images of a toe, a car wheel, a book, and a nude woman further connect differing technologies with the body, as the wheel is seen as “an extension of the foot,” the book is seen as “an extension of they eye,” clo thing as “an extension of the skin,” and electric circuitry as “an extension of the central nervous system” (34-40). The ubiquity of media is epitomized with electric circuitry, which affects not just one body part but the entire central nervous system, which is composed of the nerves in the brain and spinal cord through which we control the activity of our bodies. If we concur with McLuhan that media create new environments which in turn modify human sense perceptions and behaviors (see page 41), do we thus allow that electric circuitry affects and even directs our thoughts and the movements of our bodies?

thing as “an extension of the skin,” and electric circuitry as “an extension of the central nervous system” (34-40). The ubiquity of media is epitomized with electric circuitry, which affects not just one body part but the entire central nervous system, which is composed of the nerves in the brain and spinal cord through which we control the activity of our bodies. If we concur with McLuhan that media create new environments which in turn modify human sense perceptions and behaviors (see page 41), do we thus allow that electric circuitry affects and even directs our thoughts and the movements of our bodies?

While McLuhan discusses electric circuity in terms of television, worldwide news, and xerography, it is germane to apply his theories to the present-day technology of the internet. The union of electronic technology and the body has greatly increased since McLuhan wrote The Medium is the Massage, as we spend increasing amounts of time online. While statistics vary, the average teenager is spending around 27 hours or 44.5 hours or 63 hours online per week. This is both a physical activity, as my fingers type this blog and my eyes follow the words on the page, and an extension of the body outside of previous understandings of space and time.

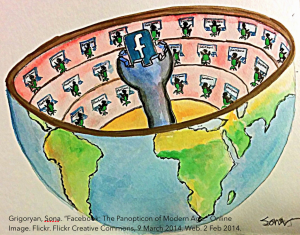

While much of McLuhan’s writing focuses on the utopian potential of electric circuity as a unifying community-building medium, it is his writing on “YOU,” the individual self, that most clearly speaks to the dangers of this technology. Accompanying the text with an image of a finger print, McLuhan writes, “electric information devises for universal, tyrannical womb-to-tomb surveillance are causing a very serious dilemma between our claim to privacy and the community’s need to know” (12). The privacy and individualism of a print-technology world is no longer possible with electric technology which quantifies and monitors us.

This brings to mind Jeremy Bentham’s 1791 architectural design of the panopticon, a![]() proposed prison with a central watchtower surrounded by a circular ring of cells. Unable to tell who is watching them or when they are being watched, it was thought that inmates would self-police their behavior. Michel Foucault later explored this concept in his book, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1975) in order to examine the non-linear and faceless nature of power relations and the force of self-surveillance.

proposed prison with a central watchtower surrounded by a circular ring of cells. Unable to tell who is watching them or when they are being watched, it was thought that inmates would self-police their behavior. Michel Foucault later explored this concept in his book, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1975) in order to examine the non-linear and faceless nature of power relations and the force of self-surveillance.

McLuhan’s description of a “womb-to-tomb

surveillance” brings the concept of the panopticon into the everyday, as online technology infiltrates the intimate details of our lives. Edward Snowden’s leaks about the NSA’s surveillance of American citizens, for example, were a tangible realization of Foucault and McLuhan’s predictions. While we are aware that we are be surveilled like the prisoners in the panopticon, we do not know who is tracking us (whether it be the government or corporations) or when. The analogy is ultimately somewhat hazy as it is debatable whether a knowledge of surveillance has caused us to self-police our actions online and offline. This has led me to wonder if my minimal presence on social media (maybe the ultimate form of self-surveillance?) and my decision to use a nom de plume is a form of self-policing?

technology infiltrates the intimate details of our lives. Edward Snowden’s leaks about the NSA’s surveillance of American citizens, for example, were a tangible realization of Foucault and McLuhan’s predictions. While we are aware that we are be surveilled like the prisoners in the panopticon, we do not know who is tracking us (whether it be the government or corporations) or when. The analogy is ultimately somewhat hazy as it is debatable whether a knowledge of surveillance has caused us to self-police our actions online and offline. This has led me to wonder if my minimal presence on social media (maybe the ultimate form of self-surveillance?) and my decision to use a nom de plume is a form of self-policing?

Beyond a nom de plume, NOMAD ETAK can also engage with our course’s theme of Indigenous new media and McLuhan’s problematic writing about Indigenous peoples. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines nomad as “a member of a group of people who move from place to place instead of living in one place all the time.” Nomad is a term that has been applied (often controversially or falsely) to Indigenous peoples in opposition to a ‘Western’ notion of home and private property. Nomad could also be used to describe a person who negotiates cyberspace, moving outside of place and time.

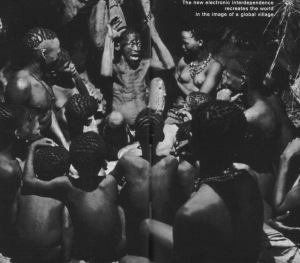

McLuhan’s analogizing of “primitive and pre-alphabet people [who] integrate time and space as one and live in an acoustic, horizonless, boundless, olfactory space, rather than a visual space” (see pages 56-57) with the electric creation of a 20th century interdependent and mythic “global village” exhibits the dangers of these kinds of comparisons. His univ ersalizing description of “pre-alphabet people” and patronizing use of the words “primitive” and “primordial” are undoubtedly racist and romanticizing. For me, this ultimately brings into question McLuhan’s early assertion that “societies have always been shaped more by the nature of the media by which men communicate than by its content” (8). Is this not also universalizing and presumptive to assume that societies, in both the past and present, have been defined more by their overarching technology than by the content of their unique cultures and communities?

ersalizing description of “pre-alphabet people” and patronizing use of the words “primitive” and “primordial” are undoubtedly racist and romanticizing. For me, this ultimately brings into question McLuhan’s early assertion that “societies have always been shaped more by the nature of the media by which men communicate than by its content” (8). Is this not also universalizing and presumptive to assume that societies, in both the past and present, have been defined more by their overarching technology than by the content of their unique cultures and communities?

While one could easily dismiss the correlation of a ‘pre-alphabet’ society and an electric technology society, Steven Loft analyzes McLuhan’s work on media from an “Indigenous cosm ological perspective” in his 2012 article, “Mediacosmology” (Loft, 171). Loft argues that if we view cyberspace as a site of interconnectivity and communication that connects the past and present, and the material and the spiritual, it is not merely like Indigenous ontologies and cosmologies.

ological perspective” in his 2012 article, “Mediacosmology” (Loft, 171). Loft argues that if we view cyberspace as a site of interconnectivity and communication that connects the past and present, and the material and the spiritual, it is not merely like Indigenous ontologies and cosmologies.

Rather, cyberspace is an Indigenous concept that has “always existed for Aboriginal people as the repository of our collected and shared memory” (175). Loft thus disrupts McLuhan’s linear understanding of time and place where each new technology chronological shaped societies from the pre-alphabet to electric technology, presenting cyberspace as a continuous Indigenous understanding of the world.

It is of note that Loretta Todd presents an alternative reading of cyberspace in her 1996 article, “Aboriginal Narratives in Cyberspace.” Rather than position it as an Indigenous concept, Todd argues that cyberspace has been formed by ‘Western’ cultures for the past 2,000 years. She writes,“A fear of the body, aversion to nature, a desire for salvation and transcendence of the earthly plane has created a need for cyberspace. The wealth of the land almost plundered, the air dense with waste, the water sick with poisons, there has to be somewhere else to go.” (Todd, 155). The ‘Western’ focus on the mind and acquiring knowledge is in opposition to an Indigenous understanding of the importance of ‘clean land.’

Both McLuhan’s utopian and dystopian understandings of electric technology are challenged and furthered by Loft and Todd. While Loft presents cyberspace as an Indigenous concept that fosters interconnectivity and communicative agency, Todd sees cyberspace as a ‘Western’ expanse of disconnection and disembodiment. Both authors, however, ultimately advocate Indigenous “cyber-warriors” who engage with (ETAK/attack) ‘Western’ understandings of cyberspace (Loft, 182). Loft praises projects such as CyberPowWow that reclaimed territory in cyberspace, while Todd advocates planning for future generations (the 7th generation) in relation to technological advancements and Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun’s project Inherent Rights, Vision Rights.

There is thus a fluidity of the body in McLuhan, Loft, and Todd’s writings. The body is both physically affected by electric technologies (with changes in our perceptions and modes of surveillance) and also extended and disembodied by cyberspace (interconnected outside of time and space).

David Gaertner

October 7, 2016 — 8:55 pm

I am very taken with the way you begin this piece, Kate, providing both a point of self analysis and a very unique path through which to critique McLuhan. The cyberspace “nomad” is a very compelling theoretical notion, which I think you could expand on in greater detail should you want to take these ideas further. I also think there is another twist to be taken on the Snowden case–it is true, of course, that agencies like the NSA are at the centre of the panopticon, but doesn’t Snowden demonstrate that cyberspace also enables the margins to return the gaze? That the distinctions between the looker and the looked at have shifted?

In any case, this post gave me lots to think about; and the writing is is lovely, fluid and engaging. Great work! I am looking forward to reading more.