The etymology of the term, ‘screen sovereignty’ indicates a meeting of Indigenous and non-Indigenous language, thought, and ontologies. Kristin L. Dowell examined the concept of screen sovereignty in her 2013 book, Sovereign Screens: Aboriginal Media on the Canadian West Coast, expanding on Tuscarora scholar Jolene Ricard’s work on ‘visual sovereignty.’ Yet, as I was thinking about how to develop my own definition of screen sovereignty I was struck by the European origin of these words. I would, thus, like to reflect on both Dowell’s definition of ‘visual sovereignty’ and the colonial connotations of language in order to create a new definition of ‘screen sovereignty.’

The etymology of the term, ‘screen sovereignty’ indicates a meeting of Indigenous and non-Indigenous language, thought, and ontologies. Kristin L. Dowell examined the concept of screen sovereignty in her 2013 book, Sovereign Screens: Aboriginal Media on the Canadian West Coast, expanding on Tuscarora scholar Jolene Ricard’s work on ‘visual sovereignty.’ Yet, as I was thinking about how to develop my own definition of screen sovereignty I was struck by the European origin of these words. I would, thus, like to reflect on both Dowell’s definition of ‘visual sovereignty’ and the colonial connotations of language in order to create a new definition of ‘screen sovereignty.’

In her introduction to Sovereign Screens, Dowell defines visual sovereignty as the “articulation of Aboriginal peoples’ distinctive cultural traditions, political status, and collective identities through aesthetic and cinematic means” (2). Dowell is quick to emphasize that visual sovereignty is not merely onscreen but offscreen, as filmmaking is sustained by the labor of the film crew and the support and engagement of Aboriginal communities. Visual sovereignty is thus an active and social process “through which Aboriginal social relationships can be created, negotiated, and nurtured” (3). Through emphasizing Aboriginal independence, traditions, and relationships, Dowell’s writing diverts away from an emphasis on filmmaking as a commercial industry and the individual director/actor genius.

In her writing on Sovereign Screens I find it interesting that Dowell continues to use the term visual sovereignty rather than screen sovereignty. In some ways, this unites online media with offline artforms, indicating a common goal among Indigenous artists to achieve artistic sovereignty through different mediums and practices.

However, the term ‘visual’ is also somewhat limiting as it neglects the importance of sound and the body in filmmaking. There is also a long history of privileging the visual within ‘Western’ art history that has been challenged in recent decades. The importance of the aural, the tactile, the body, and community has expanded definitions of art beyond visual experiences.

In my definition, I will thus examine ‘screen sovereignty’ rather than ‘visual sovereignty’ as it is more inclusive of sound and the body but also limited to online media. In light of this I have included an audio recording loop of me writing this blog. You can hear my hands loudly typing on the keyboard of my laptop and the fainter sound of my roommate practicing the bagpipes, which was unplanned but nevertheless present while I worked on this piece. These sounds remember the presence of my physical body, my eyes tracking my work, my fingers pressing the keys, and the presence of others near me while I work.

As I turn to an analysis of screen sovereignty rather than visual sovereignty, the words ‘screen’ and ‘sovereignty’ require greater analysis. ‘SCREEN,’ has dual meanings as it can be both a noun and a verb. A nounal screen describes a partition used to shelter a person or object from view, light, or heat. It can also describe a surface onto which electronic media is displayed, such as a computer or television screen. Verbally, to screen means to “conceal, protect, or shelter” as well as to “present (as a motion picture) for viewing on a screen.” As with Dowell’s emphasis on visual sovereignty as an active process, I think the verbal definition of screen is important here. Through the medium of online technology, there is opportunity to both conceal and present oneself. While there is a tendency to view the internet as a dangerous space, I think that screen sovereignty speaks to the ability of Indigenous artists to create spaces of protection and shelter online.

The word, ‘SOVEREIGNTY,’ denotes both “unlimited power over a country” and “a country’s independent authority and the right to govern itself.” There is thus a power play within the term that can suggest both outside control over a country and independent insular governing of a country. This speaks to the ongoing effects of colonialism in Canada and Indigenous movements of resistance and self-sovereignty.

It is of note that “SOVEREIGN” refers to both a king or queen, referencing a European system of monarchy, and also a British gold coin.

To encompass the above ideas, my definition of screen sovereignty expands on Kristin Dowell’s writing on visual sovereignty and includes a close reading of the words ‘screen’ and ‘sovereignty.’ Screen sovereignty is not merely visual, but includes both sound and the body. While it can be used in both a nounal and a verbal sense, I would like to follow Dowell’s example and focus on screen sovereignty as a verb, an active process where Indigenous individuals and communities can screen their thoughts, lives, and creative projects on a physical screen. They can also screen (“conceal, protect, or shelter”) these projects from non-Indigenous viewers, creating a sovereign space online. The sovereignty of this space, however, is somewhat nebulous as cyberspace can be seen as both a territory under outside ‘Western’ colonial control (see Loretta Todd’s 1996 article, “Aboriginal Narratives in Cyberspace) and an independent and protected Indigenous space.

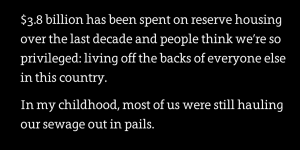

In Kevin Lee Burton’s digital media project, Gods Lake Narrows, he offers the viewer a “reserve reality” of his remote community in Northern Canada with text, photographs, and music and audio recordings. In the “About the Story” section of the website, Burton describes this project as a reaction against prevalent news stories on impoverished reserves. Through his personal narrative about his community, photographs of houses, portraits of friends and family, and audio recordings of Gods Lake Narrows radio conversations, Burton changes this narrative.

Gods Lake Narrows exemplifies not only a visual sovereignty but a screen sovereignty that incorporates sound and the body. The soft music and audio recordings are a constant undercurrent on the website, immersing site visitors into the experience of visiting this community. The sounds of the voices on the radio in  particular remind us as viewers of the real people that exist within and outside of this project. Similarly the portraits of Burton and his friends and families, looking directly into the camera lens, show us a community with the agency to look back at us. The “About the Story” section notes, “The view is anything but voyeuristic: Burton’s subjects stare out at us, storied, self-made, engaged.” Under surveillance, we are reminded of our own bodies.

particular remind us as viewers of the real people that exist within and outside of this project. Similarly the portraits of Burton and his friends and families, looking directly into the camera lens, show us a community with the agency to look back at us. The “About the Story” section notes, “The view is anything but voyeuristic: Burton’s subjects stare out at us, storied, self-made, engaged.” Under surveillance, we are reminded of our own bodies.

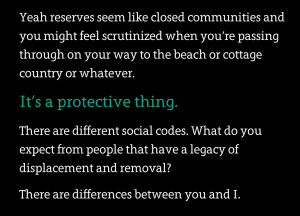

Burton’s project also speaks to the double meanings of ‘screen’ and ‘sovereignty.’ By creating this website, Burton is actively screening a narrative and visualization of his community. He has put himself and Gods Lake Narrows on view on the internet but has also screened (concealed/protected/sheltered) it through his careful curation of the site. While site visitors may click through the different pages, Burton has scripted a linear narrative about the community that directly reminds us that we are not members. On the opening page, the visitor’s physical location is noted in relation to Gods Lake Narrows and Burton writes, “I’m going to bet you’ve never visited.” He later directly states, “there are differences between you and I.”

The intended audience for Gods Lake Narrows is somewhat ambiguous which speaks to the double meaning of sovereignty. The photographs, in some ways, seem aimed at a local audience, while the text seems intended to educate non-Indigenous strangers. Burton’s photographs of reserve houses, for example, may all look the same to an outsider but reveal different details about the inhabitants to insiders.

The audio also seems aimed at a local audience who would be able differentiate between different voices. My status as a non-Indigenous urban outsider was made apparent in class when I learned that these voices were coming from radio transmitters. I had assumed they were audio recordings the artist had taken of in-person conversations.

The intention of making the local community a “primary audience” (see Dowell, 3) speaks to the sovereignty of the Gods Lake Narrows, as an Indigenous cyber space. However, through addressing a non-Indigenous audience through his text, Burton indicates the limitations of Indigenous sovereignty. While choosing and directing the narratives about Gods Lake Narrows is an act of sovereignty, Burton’s need to educate and correct assumptions about Indigenous communities speaks to the reaching sovereignty of neocolonialism.

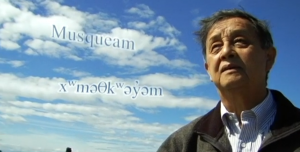

As I investigated the etymology of the words ‘screen’ and ‘sovereignty’ (their latin and French roots), I wondered how constraining it is to use English words to describe Indigenous free spaces. In Dowell’s article she discusses filmmakers Burton and Kamala Todd’s use of indigenous language in their films as examples of visual sovereignty. Is their an Indigenous word that could better describe screen sovereignty? There is of course the problem of which Indigenous language would be used to describe the concept and the dangers of universalizing. Ultimately, the use of the English language to describe Indigenous spaces allude to the current limitations of screen sovereignty. While Burton may have committed an act of screen sovereignty through taking control of the narrative about Gods Lake Narrows and making his community a primary audience, the impetus to do this and address a non-Indigenous audience through his text reveals the reaching sovereignty of the wider neocolonial state.

Works Cited

Burton, Kevin Lee. Writing the Land. Vancouver: Canada, 2007. Accessed October 29, 2016. https://www.nfb.ca/film/writing_land/.

Dowell, Kristin L. “Vancouver’s Aboriginal Media World.” In Sovereign Screens: Aboriginal Media on the Canadian West Coast, 1-20. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2013.

“Gods Lake Narrows.” National Film Board of Canada. Accessed October 29, 2016. http://godslake.nfb.ca/#/godslake.

Merriam-Webster Dictionary. “Screen.” Accessed October 29, 2016. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/screen.

“Sovereign.” Accessed October 29, 2016. http://www.merriam- webster.com/dictionary/sovereign.

“Sovereignty.” Accessed October 29, 2016. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/sovereignty.

Todd, Loretta. “Aboriginal Narratives in Cyberspace.” In Immersed in Technology: Art and Virtual Environments, edited by Mary Anne Moser and Douglas MacLend, 153-163. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996.

David Gaertner

November 8, 2016 — 4:23 pm

Very useful analysis of the word “screen” here, Kate. I love how you conceive of “screen” in its verbal form as a means of protection and put that in conversation with definitions of sovereignty. You’ve given me lots of good stuff to think about. I am not entirely sure I agree with you about the limitations of “sovereignty” as an English word (although I take your point). Just as Indigenous peoples can use technology and be no less Indigenous, I would suggest that theorists like Rickard can can use the English language and be no less decolonial. What do you think?

Great work here!