Supporting Information Literacy Goals Through Reference Services

“The purpose of reference services is to align information to flow efficiently from reference sources to those who need it.” (Riedling 5)

(Gitomer, Crouse, & Allen, 2017).

The responsibility of ensuring information efficiently flows from reference sources to students, teachers and parents has resonated the most with me through the exploration of the foundation of the reference services theme. It is one of the key aspects of being a new teacher-librarian that I enjoy: being a part of the reference process and connecting students with information to support their inquiry. It is also one of the more intimidating elements of the job. I recall not long ago when supporting a new teacher with a research assignment looking at the reference section in the library and beyond in mild panic.

The assignment specified that students were to cite both print and online sources – primary and secondary. No problem. Right? I eagerly undertook the research assignment and began to gather resources when I soon realize that not only has this topic not been explored recently in our learning commons, I essentially have 3 print reference texts and 8 books in the main catalogue. Of these texts some were a stretch as to whether they would be ‘good’. This led me to begin sourcing texts from other secondary schools in the district and I was fortunately able to bring the selection up to 45 texts, but my print references remained at 3. I was confident students would have options and be able to fulfill the criteria for the assignment, but where they ‘good’?

(“Search vs Research,” 2016)

I find myself frequently asking during the query process – is the source I am connecting a student to the best for their question? Is it current enough? Is it the best medium – would a book be better than a database? Is the content accessible for this student’s reading level? As I learn our collection more, explore our online digital resources and connect with our teachers on coursework objectives, my confidence in this area builds. This course has, however, encouraged me to reflect on research models and how to meaningfully take students from search to research with their inquiry.

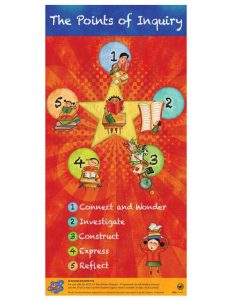

When learning about the various research models, I found the steps of connect and wonder, investigate, construct, express and reflect that form the BCTLA’s Points of Inquiry research model shape many of the research assignments that I have observed or created myself (the latter albeit inadvertently). This is likely due to the naturally intuitive shape of the POI research model coupled with a subconscious effect of absorbing the teaching techniques of other teacher-librarians I’ve worked with. (The Points of Inquiry, 2011)

As I discover more about the research process, I find myself mentally categorizing the research models. Kuhlthau is more emotionally cognizant of student emotion/behaviour, whereas Stripling and Pitt’s model has more analysis and evaluation emphasis. I like that Kuhlthau’s guided inquiry process emphasizes students’ emotional responses to the research process as they are guided through uncertainty, optimism, frustration, confusion, relief and then ideally confidence. Stripling and Pitt’s on the other hand feels very similar to Points of Inquiry, however, with the inclusion of REACTS taxonomy and the additional inquiry and evaluative steps, Stripling and Pitt’s research model feels more advanced and perhaps better suited for higher grade levels.

When comparing models and looking at the intrinsic similarities, it’s clear they all share a similar framework, but the emphasis and scope within a research step is the key difference between models. I am now in a position where I can ask – which model suits the project/class best.

Credibility of source?

I was surprised that one area that lacked mention in many of the research models was the need to evaluate the credibility of a source. In the age of “Fake News”, source credibility is a key component for inclusion in every research task that I’ve done in the library thus far. While students sit on the more current side of the digital divide, the continued support in teaching digital literacy feels relevant to most research assignments. For most students, source credibility means an evaluation that explores: who is the author; is the website reputable; is there bias?

(“Wooden dice,” n.d.)

What is a ‘good’ reference resource?

I am learning the necessity to continually evaluate the collection – does this source meet the “good” standard as a reference resource? Knowing that it isn’t always practical to weed as often as Asselin’s, Achieving Information Literacy recommends, it doesn’t mean that the exploration for better reference sources never stops – though it is hard not to feel discouraged knowing that the collection funding is grossly under standards and the viability of the next great find is unlikely to align fiscally. A ‘good’ reference resource must meet the following criteria:

- Does the scope “reflect the purpose of the source and its intended audience?” (Riedling 22)

- Is it accurate, hold authority and is there a bias?

- What is the arrangement and presentation of the resource? Will its sequence be familiar to our patrons? Does it provide clarity or intuitiveness?

- What is the relationship to similar works? Will the resource add to the collection, or will it simply overlap?

- Is it current? Will it have longevity?

- Is it accessible/diverse? Does it provide “inclusive information from different cultural perspectives?” (Riedling 23)

- How much will it cost? Is it justifiable to meet the above needs of students?

In exploring the foundation of reference services, I have been challenged to reflect on my role as a teacher-librarian and more specifically as it relates to the reference process. It is clear that in order to build a successful, supportive and efficiently used learning commons, the information literacy goals must be supported by an active search for resources and reference services on a consistent basis.

“For school librarians reference services are more than just information skills or activities; these services represent significant and meaningful engagement in a profoundly human activity, ministering to one of the most basic needs of humans—the desire to gain knowledge.” (Riedling 3)

Works Cited:

Asselin, Marlene., Branch, J., & Oberg, D., (Eds). (2003). Achieving information literacy: Standards for school library programs in Canada. Ottawa. Retrieved from http://accessola2.com/SLIC-Site/slic/ail110217.pdf

BCTLA Info Lit Task Force. (2011). The Points of Inquiry: A Framework for Information Literacy and the 21st century Learner. [Poster] British Columbia Teacher-Librarians Association. Retrieved from https://bctla.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/the-points-of-inquiry.pdf.

Gitomer, D., Crouse, K., & Allen, J. (2017, November 9). Studying the Use of Research Evidence: Methods and Measures in a Complex Field [Photograph]. Retrieved from http://wtgrantfoundation.org/studying-use-research-evidence-methods-measures-complex-field

Riedling, A. M., & Houston, C. (2019). Reference skills for the school librarian: Tools and tips (4th ed.). Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.

Search vs Research [Video file]. (2016). Retrieved from https://library.mcmaster.ca/research/how-library-stuff-works

Wooden dice form the word fact or fake – 3D Ilustration [Photograph]. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.shutterstock.com/image-illustration/wooden-dice-form-words-fact-fake-1428426371 Royalty-free stock illustration ID: 1428426371

Follow

Follow