Reference Services From a Remote Learning Commons

“Essentially every aspect of school library services has changed over the past few decades due to the emergence of new and innovative technologies. Reference skills, sources, and services are but one area that has changed to meet the needs of students in the diverse, global society of today. The Internet has become the most important reference tool in the digital age, providing many of the electronic information sources required for reference services.” (Rielding , 2019, pg. 99)

Reference services from a remote learning commons has become the ‘new normal’ for many libraries across Canada and even worldwide. On March 19th, 2020, the B.C. government closed all schools in B.C. in an effort to reduce the spread of COVID-19. “That means that more than 500,000 B.C. students won’t be returning to class after spring break. B.C. Education Minister Rob Fleming has said that schools and school districts should offer alternatives while in-class instruction is suspended” (Crawford, 2020). This news for teacher-librarians has resulted in a significant shift in how we support students, staff, parents and administrators with a now virtual learning commons.

Asselin outlines the following standards for Information and Communication Technologies:

“From the perspective of information access, information and communication technologies in the school library offer:

- Ready access during and beyond the school day

- Equitable opportunities for students who do not have computers at home

- Supervised settings for the use of the Internet and electronic, digital, and online resources.

- Increased productivity and learning through learner-focused activities

- Enhancement and extension of the curricula through integration of technologies.

- Support for a variety of teaching and learning styles.

(Asselin, 2003, pg. 46)

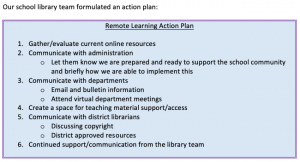

For remote learning, reference access, equitable opportunities, support for a variety of teaching and learning styles was a large part of week one’s action plan.

Re-imagining reference services:

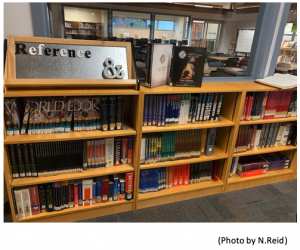

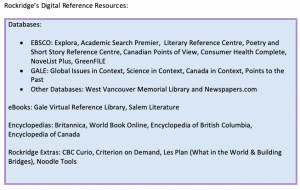

Reference services at Rockridge’s learning commons has more print resources than digital reference sources. The digital references are largely supplied by the ERAC district bundle, though we do have some additional purchases outside of that. Through the library operations folder that we maintain, we have all of the digital resource logins, passwords, vendor contacts and the licensing terms. Putting together a school specific digital resource list was the first step to supporting the school community.

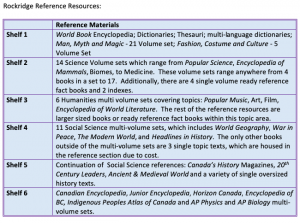

It was clear from looking at the digital reference list there were significant topic gaps within our reference collection online as compared to our print reference section. Having started evaluating our print reference section for LIBE 467, I was able to see gaps within the online references that our print selection fills. Our print reference resources comprise of 6 shelves. With the exception of the last shelf, all of the texts are organized by Dewey categorization. The inclusion of the newer AP science volumes (500s) after the Canadian Encyclopedias (970s) was a decision that related to space and access, as frequently used.

Our online references, largely miss language support texts, geography and atlas texts, as well as some of the more topic specific reference resources within the humanities and social science sections. Having said that, these print references are older texts within our collection for the most part and fall outside 15+ years old. We don’t see much use of these texts, but they have yet to be weeded or replaced.

After an digital reference resource list was generated, my library partner let administration know that we are ready and prepared to support staff with course text access, reference resources and researching projects. I also sent an email to staff that shared the following supplied information:

- Digital resources – school-based resources

- FOIPA approved resources by our district

- we also encourage all staff to supply us with any digital tool that they wish to use that is not on the approved list so that we can send to the district team for vetting and approval.

- Copyright information

- Highlights from Copyright Matters

- Rules for recording ‘read alouds’ posted online

- Canadian publishers’ information – reporting requirements and how we can help with submitting that information.

Encouraging Reference Service Engagement:

One of the challenges, I’ve found with being a remote teacher-librarian is creating that central hub like our learning commons has without being overzealous. We are cognizant to not over-inform, over email and essentially overwhelm staff with copious resources that may or may not be useful to every teacher. One of the more effective strategies we found was to let every department coordinator know that we are available to attend any department virtual meetings. This was received positively by staff and we were able to attend a number of virtual department meetings. These meetings served multiple benefits: we are able to actively show our presence and availability for support; we are able to listen to subject topics being focused on, which lets us anticipate potential reference supports; we also were able to share some of the support we can offer: not just supplying digital references, but also investigating copyright rules for specific texts, creating video support for using materials to be shared with classes. After these department meetings, we received many queries about research topics and classroom text alternatives. Week one was a busy week!

District Teacher-Librarian Collaboration:

A number of meetings outside of the school community also took place in week one. District teacher-librarian meetings as well as smaller break off meetings with the secondary teacher-librarians. Some of the topics we explored were: teacher librarian supports, effective ways to communicate how we can support our staff, students and families with essential learning, reference reviewing: vetting and approvals, copyright and FOIPA.

With the BC Government relaxing FOIPA rules until June 30th, the overarching message our district is conveying is that we must protect our students and ourselves within this grey territory. To support our district, we have been asked to do a preliminary review on a number of online sources. This evaluation follows similar guidelines to the ERAC suggestions in Appendix 5. “Consultation with resource teachers, such as teacher-librarians and technology coordinators, will provide information on how best to provide access for students. Sites should be appropriate for the grade level and language of instruction while being readable and accessible. The school’s technology resources will have an impact on what type of sites are of practical use. Teachers must also ensure students are aware of school district policies on Internet safety and computer use.” (Evaluating, Selecting, 2008, pg. 136). Our district is evaluating digital resources based on: does it connect/support essential learning; is there a comparable resource already licensed; do we have to login or create accounts; grade appropriate; is the site safe or free from advertising; accessible to all; education specific?

The district guidelines mirror Riedling’s philosophy. She states, “a Web resource may be different from a print source, but it remains essentially the same in purpose and scope. Web materials can make steps easier, considerably more efficient, and certainly more comprehensive. However, each resource must be evaluated for authority ad appropriateness for the question at hand.” (Riedling, 2019, pg. 103)

Some great sources of free reference sources are being shared within the teacher-librarian community:

- BCTLA: Gale Free access, Curio, Follett e-Learning, Audible Stories, REMSS resource list

- Richard Beaudry: 25 Sources of Free Public Domain Books, but many resources posted on his twitter

- Library of Congress: opportunities to engage with authors from anywhere in the world

With the volume of free resources available, we are collectively working together to ensure that teachers are equipped with the best resources for their courses. Teachers are encouraged to submit digital resource requests for review. Not all resources are approved, and it is conveyed to staff that the approvals are district specific and what may be approved provincially or in another district isn’t necessarily greenlit for us. The approved resources are officially greenlit at a district level and shared with all staff. For example, in our district we are not permitted to do 2-way teleconferencing, nor are we permitted to use Zoom. However, we have virtual meetings with staff and are encouraged to use Google Meet and Microsoft Team. How-to videos have been circulated to staff to ensure ease of access like the one here for Google Meet. Where possible, alternatives are provided.

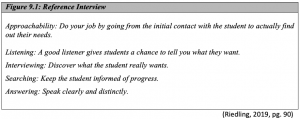

Virtual Reference Interviews:

Once staff were set up with the basic information on how the library team can support them, individual teacher requests were being received. The first direct contacts were about current texts or movies. Can we source approval or do we have an alternative? My teacher-librarian colleague reached out to a number of publishers and was able to secure digital copies of some texts, or was able to share publisher’s temporary ‘relaxed’ copyright rules. For films, this has been more of a challenge. One of our Social Studies teachers wanted to show a movie on the Lavender Scare which explores LGBTQ treatment in the US during the Cold War, but we discovered that digital access was not available. After searching were able to share a Canadian perspective alternative with TVO’s Fruit Machine. We have been less lucky however sourcing a digital copy for The Handmaid’s Tale 1990 film, which we can access via DVD, but permissions to rip and upload are not enabled. Apple and YouTube enable users to pay for a digital copy but this is for single user licensing and not classroom sharing. The majority of films used to support classes, we are finding will have to come from the following sources: Criterion on Demand, NFB, public free to access sites like TVO, West Vancouver Memorial Library’s Kanopy and Indieflix. The latter requires the additional step of ensuring all students have WVML cards, which most do. Those that don’t will be helped with acquiring one remotely.

The other requests we are now starting to receive, and likely will have more as the weeks pass are research support queries. My recent reference query was a request to support students researching revolutions. I conducted a brief reference interview over email and ascertained that the teacher was looking to have general information for her students to find any revolution: cultural or political. They will have to retell it through 5 elements of story and include at least one primary resource. I went through our databases as well as the temporarily free Gale in Context High School. I created a reference resource document, outlining research steps.

The next step was creating video support, showing how to navigate through Gale in Context High School. The video was designed on Mac screen capture software and slightly edited in iMovie for this assignment to redact the passwords. I was tempted to use other software, but for the purposes of this reference query and time management, these were the most effective creation tools to me.

(Video by N.Reid)

My video was deliberately short and serves to show students how to navigate and select primary resources. I know that many students will stop at this stage, and the research document I created can adequately support from this point forward. However, some students will need further explanation and I created a second video that shows students how to navigate our library page and select both databases and encyclopedias. For most students this will be a refresher, but there are some who are new to the school, that may have missed our orientations.

(Video by N.Reid)

The above supports for a remote learning reference query, worked well for supporting students and offer similar support to an in-person library lesson. The caveat will be questions. From teaching library lessons, there is an opportunity to have students ask questions on the spot and reply. With this type of remote learning set-up, that instantaneous feedback isn’t viable and we can only encourage students to ask us if they have questions. Another drawback is not being able to ‘read the room’. As a teacher, you are looking for class receptiveness and when you have ‘lost’ a group, you are able to reset and either backtrack or further elaborate. An online video does not offer that type of engagement. The positive however, is that students can rewind if they missed a step and learners are able to move at their own pace. We foresee many more of these types of reference queries over the next few weeks and look forward to discovering more ways to support students and teachers.

After Remote Learning:

The current status of offering remote reference services has variable intensities. The first week offering teacher supports was extremely busy and also rewarding. Now that teachers are diving into content, we are seeing more topic specific research queries. We have yet to received direct contact from students for reference services, but anticipate this will happen with assignment engagement. The experience of offering remote services is new to many of us, but I can’t help wonder how it will shape our perception of reference services when we return to the physical learning commons.

Having done a direct comparison between the print collection and our electronic collection, the glaring omissions within digital reference resources cannot be overlooked. The area that feels weakest for support is within languages. Having mentioned earlier a number of the print references that don’t have digital resource counterparts, are from texts that are generally 15+ years older and fail the both Crew’s MUSTIE scale and Asselin’s standards, technically they should be weeded. Budget, use and better replacements are factors that lend to why the resource is still housed within the collection. An aggressive evaluation of usage will need to be observed to determine whether many of the older print references are actually being used. This would enable a more focused buying approach to replace some print collections and also the digital resource for offsite use.

Works Cited:

Asselin, Marlene., Branch, J., & Oberg, D., (Eds). (2003). Achieving information literacy: Standards for school library programs in Canada. Ottawa. Retrieved from http://accessola2.com/SLIC-Site/slic/ail110217.pdf

BCTLA Executive. (2020, March 22). A Word from the BCTLA Executive during this time. Retrieved April 5, 2020, from https://bctla.ca/2020/03/22/a-word-from-the-bctla-executive-during-this-time/

Beaudry, R. (2020, April 7). 25 Sources of Free Public Domain books [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/RBeaudryCCLE/status/1247573556138872832

Canadian School Libraries (CSL). (2018) “Leading Learning: Standards of Practice for School Library Learning Commons in Canada.” Retrieved from: http://llsop.canadianschoollibraries.ca

Crawford, T. (2020, March 19). COVID-19: Five things to know about B.C. school closures. Vancouver Sun. Retrieved from https://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/covid-19-five-things-to-know-about-b-c-school-closures/

DoIT Training at Stony Brook University. (2020, March 10). Using Google Meet to Record a Meeting or Narrate Slides [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-bEJEvf6JFk

Evaluating, Selecting and Acquiring Learning Resources: A Guide [Guide]. (2008). Retrieved from https://bcerac.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/ERAC_WB.pdf

Larson, J. (2012). CREW: A Weeding Manual for Modern Libraries [Manual]. Retrieved from https://www.tsl.texas.gov/sites/default/files/public/tslac/ld/ld/pubs/crew/crewmethod12.pdf

Library of Congress: Engage! (n.d.). Retrieved April 5, 2020, from https://loc.gov/engage

Noel, W., & Snel, J. (2016). Copyright Matters!: Some Key Questions [Pamphlet]. Retrieved from http://cmec.ca/Publications/Lists/Publications/Attachments/291/Copyright_Matters.pdf

Reid, N. (2020, April 6). Revolution Intro Research [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z2uZbyRqodQ

Reid, N. (2020, April 6). School Database Review [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cz7vteoaP98

Riedling, A. M., & Houston, C. (2019). Reference skills for the school librarian: Tools and tips (4th ed.). Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.

Welcome to the Home Page of Rockridge Library Learning Commons. (n.d.). Retrieved April 2, 2020, from http://www.sd45slc.ca/about-rockridge-library.html

Follow

Follow