This past weekend, I was on a discussion panel for the documentary film Anote’s Ark, which follows the former present of Kiribati, Anote Tong, in his quest to bring the plight of Kiribati’s people in the face of climate change to the western eye. This sounds harmless enough, but since the film was released a new president was elected, the filmmaker was banned from entering the country, and the Kiribati ambassador to the United States attempted to prevent the film from showing at Sundance Film Festival (this is according to the filmmaker, you can read his take here).

It’s important to know that the current president of Kiribati objects to this film not because he doesn’t believe in climate change, but because of the language and messaging the film employs. “We are not sinking, we are fighting” is a battle cry heard all throughout the Pacific. The dominant Western narrative about climate change is one in which people who live in the Pacific Islands are helpless in the face of rising sea levels and erosion, and Anote’s Ark uses language that reinforces this narrative. For example, the first thing you see when you visit the film’s website is the question, “What if your country was swallowed by the sea?” While it is true that Pacific Islanders are not responsible for creating climate change, they are far from helpless when it comes to facing its effects, and language such as that used in Anote’s Ark removes their autonomy.

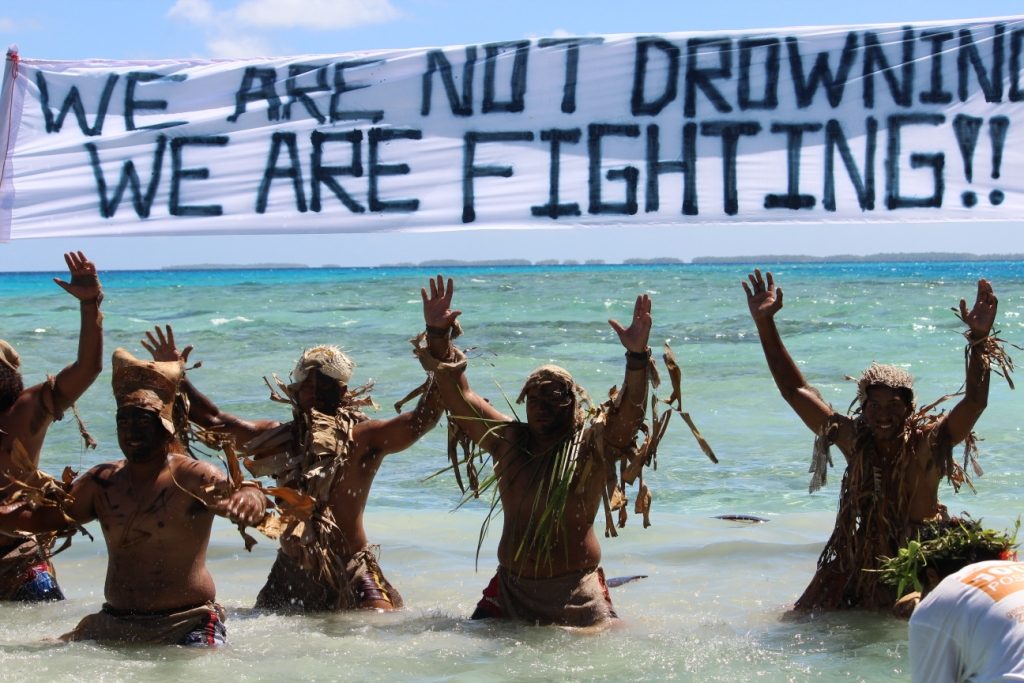

Tokelau warriors participate in the Pacific Warrior Day of Action in 2013 (image via 350.org).

I was asked to be on the panel because I had just returned from Kiribati, where I spent two weeks scuba diving around Tarawa and Abaiang Atolls with my advisor, Simon Donner, and master’s student Heather Summers, to study the coral reefs for my Ph.D. fieldwork. While we were there, we worked closely with staff from the Kiribati Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources Development. I have also worked with communities on other “sinking islands”: in the Marshall Islands (just north of Kiribati) and in the outer islands of Yap in the Federated States of Micronesia. While these places are different in many ways, they are all united by their status as lands on the frontline of climate change. However, none of these communities are ready to give up the fight to save their homelands. Language evoking drowning and disappearing islands gives the impression that their fate has already been determined.

Before we left, we had an opportunity to share our research with people from various ministries in the Kiribati government (mainly, the Ministry of the Environment, Lands and Agricultural Development, the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources Development, and the Ministry of Education). These ministries are being proactive and doing lots of great work to slow the effects of climate change. For example, the Ministry of the Environment has planted mangroves in various places in Tarawa’s lagoon to slow erosion, and they appear to be doing well. Healthy coral reefs can play an important role in protecting low-lying atolls like Tarawa and Abaiang from erosion because they break up waves that can cause erosion (in fact, coral reefs dissipate wave energy by an average of 97%). Everyone at the meeting was eager to brainstorm potential ways to protect and restore reefs around the atolls, and we discussed our preliminary findings and their potential implications for over an hour after the presentation. For me, the meeting was a much-needed reminder of how crucial healthy reefs really are to Pacific Island communities; this is easy to overlook from a Western viewpoint, in which people tend to think of their value mostly in terms of tourism and aesthetics.

Pacific Climate Warriors lead the People’s March in Bonn, Germany on November 4, 2017 (Image via Hoda Baraka, 350.org).

Anote’s Ark featured a scene from the COP23 meeting in Bonn, Germany, in which a group of Pacific Climate Warriors led the People’s March on November 4, 2017, a gathering of 20,000 people demanding action from the international community on climate change. This international congregation of people united behind the Climate Warriors who chanted as they marched, “We are not sinking, we are fighting”. One of these warriors was Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner, a Marshallese activist, poet, and teacher, who was also featured giving a speech. She has given talks all over the world, including one during the opening ceremony of the UN Climate Leaders Summit in 2014 (you can watch it here). Kathy has actively spoken against the narrative that Pacific Islanders are helplessly waiting to sink into the sea. I’ll end with a poem she shared that was written by another Pacific Climate Warrior named George:

Yesterday

Sounded like the calm ocean breeze blowing through the Baka Tree. The laughter of my Dreu’s* making jokes about the Baigani incident. The mixing of Yaqona at 10am and the call from across the village going mai, mai, mai, dua mada na bilinimua.

Yesterday tasted like sui mada by my mother. Fresh fish and Yaqona made by my people.

Yesterday looked like the Bula smiles and respectful gaze of my elders. It looked like hope.

Yesterday smelt like the voivoi picked to weave the finest mats, like the masi used to wrap my son and daughter the first time they came home.

Yesterday felt like

We are not drowning.

We are fighting.

*Translations:

Yaqona – Kava

Mai, mai, mai, dua mada na bili ni mua – come, come, come, one farewell mix

Sui – meaty bone soup

Voivoi – pandanus leaves

Masi – Tapa

Baigani – Egg plant

Drue’s – traditional address for people from Vanua Levu, the other bigger island in Fiji.

Sara Cannon is a graduate fellow in the Training Our Future Ocean Leaders program.

site para discussoes sobre saude e medicamentos