“I kept reading right to the last page.” (63)

As plainly articulated in this quote, I took in absolutely everything from this book. I adore this book. This is easily my favourite book for this class– perhaps my favourite book I’ve ever had to read for any class. Due to this… my blog post is extremely lengthy. I have split this into 6 nice sections though (one for as many dreams as are described in the book). Feel free to only read one of the 6!

The Avocado Tree

In the section “Illusions,” the gecko describes a scene of two boys imitating turtle doves as one climbs an avocado tree. The passage is aiming to indulge the reader into the greater idea that something that is a mere illusion when not known to be false is treated with as much respect and belief as a reality.

Although I adored this section for the powerful yet simple message it conveyed, to me, the imagery of the boy climbing the tree and the modality of the sentiment is what allowed me to feel such a connection.

Two summers ago, I had the opportunity to work abroad in Spain for a family. While there, I visited the family’s grandparent’s farm in which there was a large blooming avocado tree, ripe with fruit. The boys I worked for were too young to climb the tree to its height and reach the avocados, as the ripest fruits were at the top. However, as I am a self-labelled pro tree climber, this was a breeze. And in fact, collecting the avocados (43 to be exact) was one of my greatest highlights from that trip. As this was my first day on my new job (in a foreign country which I did not speak the language, climbing a tree I had never seen in my life, and working for a family I had yet to integrate with) I was terrified. However, climbing that tree (to the very top might I add) and passing down avocado after avocado, my fear was masked by my bravery. The kids idolized me on the car ride back from the farm, and the next day I proudly ate my harvested avocados. I think alike to how the leaves of the trees in the novel disguised the boys as turtle doves, the avocado tree in my situation disguised my fear as excitement. And perhaps, like how in this novel the lies often merge with the truth, my “lie” of preparedness soon became my reality.

Red Ants

In the section “Rain on Childhood,” Felix recounts his childhood, and specifically the death of his dogs. In this passage, he discusses fire ants. Although much more occurs in this section, and many of those other ideas stood out to me as well, I could not ignore my personal connection to this attack in specific. The day of my 5th birthday I was in North Carolina visiting my grandparents and uncles with my mom and brother. The trip had been a lovely success up until the fateful night. We spent the day riding my grandfathers’ tractor which I always loved. Then night came. I was out in my uncle’s yard playing with my brother when all of a sudden, I felt fire shoot up my leg, then up my other, then my arms, until I was fully ablaze. Not a real fire of course, as this passage is not about that– it’s about ants. Fire ants swarmed my little body and attacked wherever they could until all I could feel were tears freeing themselves from my horror-stricken eyes. My mom and grandma came to my rescue immediately and took care of me. Luckily, I did not face a fate similar to Felix’s dogs.

Now, did you believe this story? I believe this story. But do I know that this story is real? Do you know? No. Did I believe that Felix’s story is real? Did he believe it was real? Is it real? Is any of this real?

Well, I do know (or think I know) in my case that there is some truth to my story. I know that I was in fact attacked by fire ants, I know that it occurred at my uncle’s house, and I know I was quite young and that it was quite painful. I don’t know if I was five though, or if it actually occurred the night of my birthday, or if the birthday I was celebrating on that trip was my fifth. I also don’t know if this occurred in North or South Carolina, as my relatives live near the border (some on one side and some on the other). And do I remember the pain? No. But I have been told of this. I have been told of my tears and cries and scars on behalf of my mother, and I choose to believe her.

I think this is all rather fascinating though. Our memories are so often altered (whether slightly tweaked or entirely fabricated) and sometimes without even our knowledge. So, for those who choose to think that Felix’s profession is immoral, are we as humans acting immorally (though unconsciously) every day by rewriting our memories?

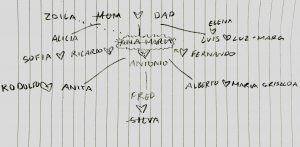

Great Grandfather

On the note of false memories, I would like to briefly discuss Frederick Douglass. This is a figure who is mentioned a handful of times throughout the novel as being the (fake) great grandfather of Felix. Last year I happened to read the Narrative Life of Frederick Douglass. So, when he was first mentioned in this novel as being related to Felix, I was quite speculative (knowing a decent amount of his life story). I didn’t remember certain details the same as in this book, yet who was I to recall greater than the author? I felt quite proud of my immediate speculations once it was clear that such relation was a mere fabrication.

However, I do think it is interesting that Felix selected Frederick Douglass to hold this prize role in his own personal family tree. As a professional creator of pasts, one would presume that Felix would preserve the finest of backstories for himself– the cream of the crop. Knowing this, I am curious, do you guys think that Felix’s actual great grandfather would find offence to his erasure and “upgraded” replacement?

I am curious as I too, in a sense, have replaced my great grandfather. My great grandparents got divorced many years ago, before even my mother was born. My great grandmother then remarried another man– I’ll call him Mac. My mom grew up calling Mac her grandfather, although her biological one was still around, and she would visit him often too. Growing up, I always thought of Mac as my true great grandfather (and I was lucky enough to still have him around up until a year or two ago). I remember once, when I was around 10, I went to visit my actual great grandfather. He was living in a care home and was at the end of his time. The curious thing is that I don’t think I quite understood who he was to me until years later. I thought perhaps he was a great uncle, maybe even my mother’s maternal grandfather? Yet no, he was what Mac was to me. He was a duplicate– and an underrepresented one at that. I worry at times that perhaps he felt excluded from my family, or even from my mind.

Suicide

I am sorry that this may get a bit dark. I will try to keep it light! Yet as we know from this novel, with light there must be shadows. And even something so full of light, like Angela, can possess a darkness so deep that it kills. My uncle was one of these lights. A light so bright that its shadow had to be of the same depth.

In the section “My First Death Didn’t Kill Me,” the gecko is recounting his experience with suicidal ideation in his previous human life, and in particular, an incident in which he almost went through with this act.

I think I will always think about my uncle when suicide is mentioned in media, conversation, or thought. He passed away just over four years ago now. A fascinating aspect of this though is that it almost was not a fact to me. With just one lie from my mother, this may have never been a reality. In fact, for many people in his life (including his partner while he was alive) his death was the result of heart failure, or something mundane of the sort. Due to personal reasons, my grandparents thought it best to keep his way of death a secret. They wanted to take reality and warp it. I think to this day they still believe that for me, reality is warped like that– but no, I am aware of the truth.

Part of me wonders if this could somehow be the case for the gecko too. I doubt it is, but I think that re-reading this section under that lens, it alters my reading of it in a fascinating way. (If you imagine that at the end, he does in fact die, just no one knows… and instead his story is forged into some other, some happier tale). It’s all very interesting to me. Personally, I do much prefer the written ending to that story though– the light and hopeful one. The one that ends in dreams, in life.

Portugal

I am sandwiching here into my post a very small and comparably insignificant connection to this novel (as I am sure the rest of these make quite the heavy read). Basically, I thought it was super cool how the novel included reference to many other places in the world. This includes, but not limited to: Portugal. I didn’t really know much about Portugal at all until a week or two ago, as I am coincidentally planning a trip to visit there. While planning, I randomly investigated the island of Madeira, and less randomly, the city of Lisbon as well. Both places are mentioned in the novel (Madeira only once or twice I believe, but Lisbon amply). I am not sure why, but I just felt extra prepared for this novel having recently researched more about Portugal, and inversely, through reading this book I am now feeling more prepared and excited for my upcoming travels! I think it’s rather neat how things can feed into one another like an endless circuit.

Reality Catfisher

As one who has struggled a lot through my life trying to grapple with who I am, especially throughout my early teen years, this book spoke to me in a unique way– above all of the previously mentioned connections (far, far above). As someone who has always had a very active imagination, and as someone who used to not particularly like myself much (boo who… but all is good now!) I used to spend my time fabricating lives of my own. I would live in these realities often– coming home from school and living these lives by playing online games and telling myself I was gaming as someone else. I was addicted to such play pretend. At times I think I didn’t even know who I was– only the stories I fabricated. There was no real harm to this– or none charged with aggression (very similar to Felix’s position I like to think). However, these years of isolation from myself, and my addictive indulgence in what to me feels essentially like catfishing (though not the classic form) truly staggered my development I believe. I missed out on real connections, real hobbies, and honestly, just simple reality. I doubt I am explaining my situation all that well– but I think this is purposeful (as I am quite ashamed of this past of mine). In many ways, I wish this part of young me was simply erased, demolished, overturned, or overwritten. I wish I could ask Felix to write to me a fictional early adolescence (one rich of family, friends, and identity), but this is impossible. I must accept my current past, as it is cemented.

I sandwiched some more thoughtful questions into my connections, but I also have a very odd yet specific request. Unfortunately, my copy of this novel for some odd reason is missing page 155– a page which lies at the heart of the climax!! Please if someone could summarise this page for me, I would much appreciate it. I still understood this scene, and the book, but as a lover of this novel, I am greedy for any extra page I can get!