Please update your bookmarks to philippinestudiesseries.wordpress.com. Maraming salamat!

Author: Caroline Chingcuanco

Introducing the Mahal (2) Art Exhibit

In his essay Ang Pag-Ibig, Filipino revolutionary, Emilio Jacinto, writes that love is the promise of liberation and joy for a people in suffering.

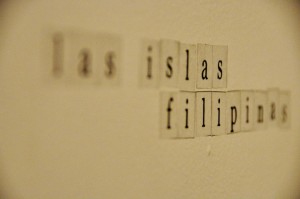

The Tagalog word ‘mahal’ translates into ‘love.’ It refers to that which is dear, but also means expensive. Perhaps Jacinto’s promise of fulfillment is also a costly one.

Photography by Edsel Yu Chua and Deyan Denchev

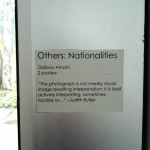

Photos from the Mahal (2) Art Exhibit and 2012 Professionals Conference

Photos from Usapan 2: Monitoring Canadian Mining in the Philippines through Social Media

A video of the presentation is soon to follow.

Video from Mobit at the Third People’s Mining Conference

You can follow Mobit Mindanao on:

Facebook: Mobit Mindanao

Twitter: mobit_cc

Youtube: MobitTV

Blog: Mobit Mindanao

Mobit Mindanao is looking for volunteers who can translate their blog posts from Bisaya to English. Please send an email to mobitmobit@gmail.com for details.

SJ Kerr-Lapsley, a fourth year undergraduate student at UBC, attended the opening night of the MAHAL art exhibit held at the YACTAC Gallery (October 2011) and found herself inspired by the exhibited works. Here is the final paper that she wrote — a result of her engagement and conversation with the exhibited works, particularly Chaya Go’s “ancients.”

Castilian Friars, Colonialism and Language Planning:

How the Philippines Acquired a Non- Spanish National Language

by SJ Kerr-Lapsley

4th year, UBC Anthropology

The topic of the process behind the establishment of a national language, who chooses it, when and why, came to me in an unexpected way. The UBC Philippine Studies Series hosted an art exhibit in Fall 2011 that was entitled MAHAL. This exhibit consisted of artworks by Filipino/a students that related to the Filipino migratory experience(s). I was particularly fascinated by the piece entitled Ancients by Chaya Go (Fig 1). This piece consisted of an image, a map of the Philippines, superimposed with Aztec and Mayan imprints and a pre-colonial Filipina priestess. Below it was a poem, written in Spanish. Chaya explained that “by writing about an imagined ‘home’ (the Philippines) in a language that is not ours anymore, I am playing with the idea of who is Filipino and who belongs to the country” (personal communication, November 29 2011). What I learned from Chaya Go and Edsel Ya Chua that evening at MAHAL, that was confirmed in the research I uncovered, was that in spite of being colonized for over three hundred and fifty years the Philippines now has a national language, Filipino, that is based on the Tagalog language which originated in and around Manila, the capital city of the Philippines (Himmelmann 2005:350). What fascinated me was that every Spanish colony that I could think of, particularly in Latin and South America, adopted Spanish as their national language even after they gained independence from Spain. This Spanish certainly differed from the Spanish in neighboring countries and regions, as each form of Spanish was locally influenced by the traditional languages that had existed before colonization, but its root was Spanish and it identified itself as Spanish. How then, did the Philippines managed to come out of colonization by that same country, with a Filipino language that is locally influenced by Spanish, rather than the other way around? It was this question that prompted my paper. Read more…