“Put on your sunscreen”—damaging air mass could drift far south.

Main Content

Stratospheric clouds in the Arctic (file picture) worsen ozone loss, experts say.

Photograph from Picture Press/Alamy

Christine Dell’Amore

National Geographic News

Published March 22, 2011

Spawned by strangely cold temperatures, “beautiful” clouds helped strip the Arctic atmosphere of most of its protective ozone this winter, new research shows.

The resulting zone of low-ozone air could drift as far south as New York, according to experts who warn of increased skin-cancer risk.

The stratosphere’s global blanket of ozone—about 12 miles (20 kilometers) above Earth—blocks most of the sun‘s high-frequency ultraviolet (UV) rays from hitting Earth’s surface, largely preventing sunburn and skin cancer.

But a continuing high-altitude freeze over the Arctic may have already reduced ozone to half its normal concentrations—and “an end is not in sight,” said research leader Markus Rex, a physicist for the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research in Bremerhaven, Germany.

Preliminary data from 30 ozone-monitoring stations throughout the Arctic show the degree of ozone loss was larger this winter than ever before, Rex said.

Before spring is out, “we may even get the first Arctic ozone hole … which would be a dramatic development—one which would make it into coming history books,” he said.

“It’s too early to call, but stay tuned.”

Atmospheric chemist Simone Tilmes, who wasn’t part of the study, agreed.

“We do not know at the moment how large the ozone hole in the Arctic will grow, because the thinning of the ozone layer is happening right now,” said Tilmes, of the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colorado.

Full confirmation may require computer simulations and satellite measurements, which study leader Rex said would “be very useful to provide an independent view of the ozone loss this year.”

An ozone hole is an area of the ozone layer that is seasonally depleted of the protective gas—such as the well-known hole over Antarctica.

(See “Whatever Happened to the Ozone Hole?”)

“Beautiful” Clouds Harbor Ozone-Fighting Chemicals

In the 1980s scientists realized chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and other ozone-depleting chemicals—then widely used in aerosol hairsprays and refrigerants, for example—were degrading the ozone layer.

The 1987 Montreal Protocol initiated a global phase-out of CFCs, replacing them with alternatives that don’t destroy ozone. However, CFCs can persist for decades in the stratosphere—the Antarctic ozone hole is still there, though it’s expected to grow smaller in coming decades.

Once in the upper atmosphere, CFCs break down into chlorine atoms, which, when activated by sunlight, destroy ozone molecules.

Cold temperatures speed up this process through polar stratospheric clouds (see picture), “beautiful” and still little understood formations that occur once stratospheric temperatures drop to at least -108 degrees Fahrenheit (-78 degrees Celsius), Rex noted.

The clouds provide “reservoirs” for inactivated byproducts of chlorine. On the surface of the cloud, these byproducts react with each other and release “aggressive” chlorine atoms that attack ozone molecules.

The whole process stops as soon as it gets warmer and the so-called Arctic polar vortex breaks up, Tilmes said.

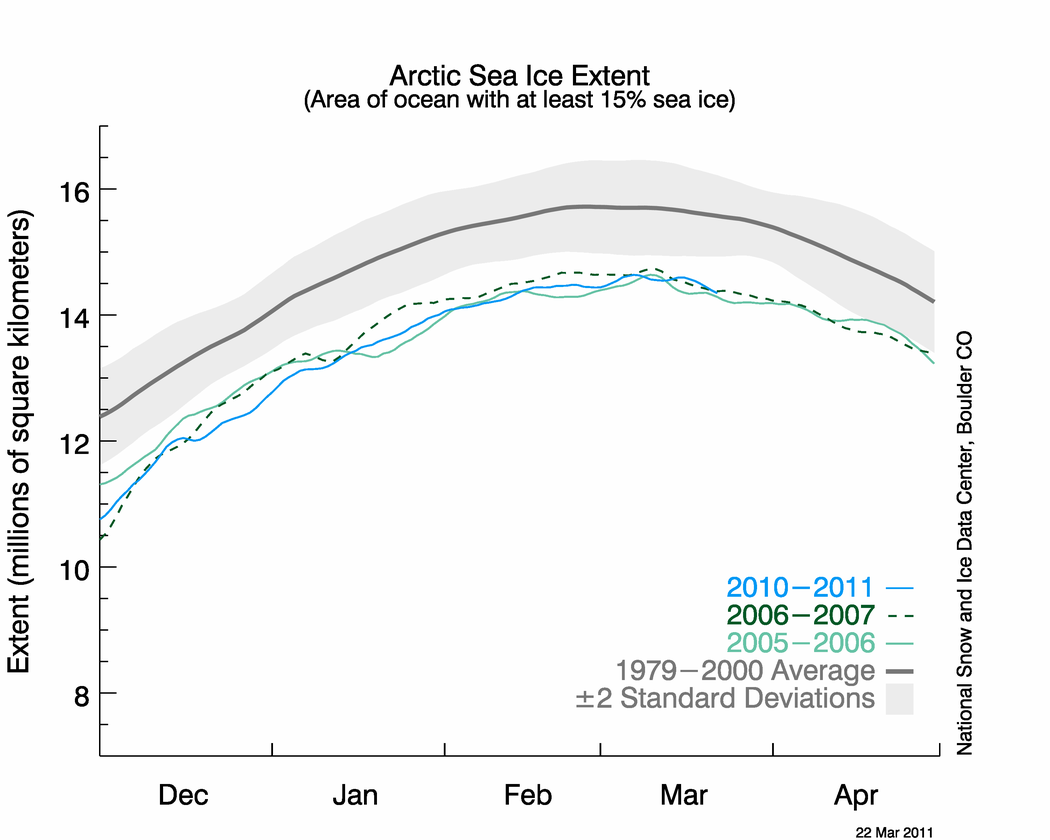

At about 6 million square miles (15 million square kilometers), or 40 times the size of Germany, the Arctic polar vortex is a frigid air mass that circles the North Pole in winter.

Warming Link to High-Altitude Cold Snap?

The cold snap is no coincidence, research leader Rex added.

“This is the continuation of a long-term tendency that the cold Arctic winters have become colder,” Rex said.

And global warming may drive this trend, he added. As greenhouse gases trap heat in the lower levels of the atmosphere, the higher levels tend to cool, he said.

Of course, the “process is more complicated than this simple explanation”—there may be many ways in which greenhouse gases influence high-altitude temperatures, he added.

Low-Ozone Air to Fly South for Spring?

Any spike in UV radiation can impact both the Arctic ecosystem and human health, research leader Rex noted. For instance, more sunlight can slow the growth of certain species of ocean algae that provide food for larger organisms—and whose absence can have reverberations up the food chain.

(See “‘Crazy Green’ Algae Pools Seen in Antarctic Sea.”)

More worrisome, Rex said, is that ozone-depleted air can catch a ride south to more highly populated areas with the Arctic polar vortex.

Low-ozone air is often pushed southward to 40 or 45 degrees latitude by natural atmospheric disturbances, Rex said.

A low-ozone air mass’s southern “excursions” can take it as far as northern Italy in Europe or New York or San Francisco in the United States, he said.

The rapidly shifting vortex might last into April, when people are starting to spend more time outside, NCAR’s Tilmes noted.

“A good message for people [is] to just be aware that this is a year where ozone will be likely thinner this spring.

“You should watch out for your skin and put on your sunscreen.”

Rex noted that, however, that since the mass is constantly moving, low-ozone episodes would only last a few days in a given region.

Rex also said this winter’s decline in ozone doesn’t mean that the Montreal Protocol isn’t doing its job.

“People could mistake that and say we have banned CFCs and [it] doesn’t seem to work,” he said.

“That’s not the case. It’s just the timescale—CFCs take so long to disappear from the atmosphere.”

Sampling bottles

Sampling bottles

Dr Helen Findlay and Dr Victoria Hill

Dr Helen Findlay and Dr Victoria Hill